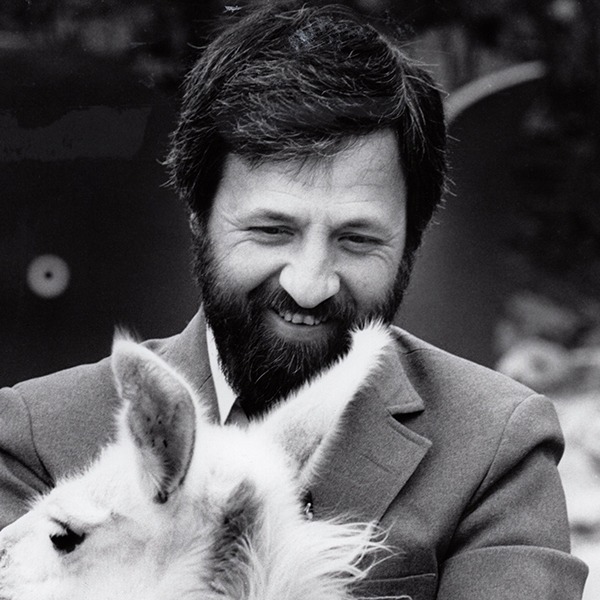

I’m Bill Boever, or William Joseph Boever, born in St. Louis, December 27th, 1944.

And what was your childhood like growing up?

Well, I grew up in South St. Louis, was a middle class family, probably lower middle class, in terms of wealth or whatever. But very close community, very much involved in the church and school, Catholic community. There was, almost all the people on the block were Catholic. We lived, maybe a half a block away from the church and school. So growing up was with a lot of others there, and it was, part of growing up was the priests of the parish. And so that’s why when it came to what was I gonna do, I thought, “Well, that would be interesting to be a Catholic priest.” And so when it came to high school, I went to the seminary, and I was in four years of high school and two years of college, and great guys there. I mean, I’m still friends with the people that I went to school with, they’re very intelligent. I mean, it was difficult, had to study all the time, but that was where I grew up.

What did your parents do?

My father was a painter, he worked for Monsanto Chemical Company, painted buildings and pipes and so forth in the chemical plant, and my mother was a homemaker. And you mentioned the zoo.

I mean, you mentioned that you were gonna go to the seminary, but what are your earliest memories of zoos?

We always went to the zoo, St. Louis Zoo, at least twice a year. My parents didn’t even own a car. We would get on the bus and ride to the zoo. At that time, the zoo’s in Forest Park. We would get off the bus with our jug of Kool-Aid and our picnic basket and find a picnic table in the middle of the park, and set it up there. And we would leave it sit there, and we’d go into the zoo. Come out at lunchtime to have our snack, and then leave it all on the table, and go back in the zoo for the afternoon, and then get on the bus and go home.

And were there any animals that you were drawn to that were favorites of yours, as you recollect, or just, it was an enjoyable day?

Well, we tried to see everything there was to see. There was not necessarily one that was more attractive to me than the others. At that time, the zoo had a three animal shows. We had a chimpanzee show, an elephant show, and a lion or big cat show. And so we made sure we saw all the shows, and we went to all the buildings. Primarily at that time, there was a reptile house. There was a primate house, a monkey house, and bird house, and then the outside antelope yards.

Do you think going to the zoo as you did, drew you to what you have spent your life doing?

Or how did that switch from being and wanting to go into the seminary, when did that take second to something else that you were thinking about?

I always enjoyed the zoo, but it was not something that I thought of as a profession, I guess at that time. I always enjoyed animals. You know, I would collect turtles or various reptiles that we could catch at the park. Had a little squirrel for a while, whatever, but that was the extent of it.

So when did you first start to think about working as a, not necessarily at the zoo, but working as a veterinarian and going to school to do that as opposed to becoming a priest or going to the seminary?

Well, once I left the seminary, when I decided I didn’t want to do that, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I went to the University of Missouri, and I moved around a little bit. I was interested in forestry, I was interested in conservation, I was interested in wildlife. Veterinary medicine was not on the horizon. I didn’t know any veterinarians. I thought of a veterinarian as somebody that grew up on a farm and was familiar more with the farm animals. And while I was at the university, I met a number of other veterinary students, and realized that a lot of the veterinary students didn’t grow up on a farm. They grew up in, you know, a more metropolitan area.

And so I got more interested and applied. I didn’t have all the credits that I needed right away. But after I got my degree, and continued studying at the university, I eventually got into veterinary school. But even when I was in, I wasn’t looking at zoo medicine. I was just open to any avenues that were available.

So you just, you thought being a veterinarian would be, it just appealed to you, it was fun, or you could help?

I mean- and I liked working with them. I probably, I really got interested in farm animals more so when I was in veterinary school. And so I had previous, in high school and early part of college, I worked at Monsanto Chemical Company as a chemical operator during the summertime, ’cause I had to earn my own way to school. And so once I was in veterinary school, after a few years, I said, “Well, I better get a job working with animals somewhere during the summertime.” And so between my second and third year of veterinary school, I started looking around. Well, I gotta work for some veterinarian someplace, and there weren’t any jobs available. I kept looking and looking and nobody had anything. And so I thought, “Well, I’ll try the zoo.” And I went, and at that time, met a veterinarian who was there. He wasn’t the zoo’s veterinarian, but he was doing work for Washington University at the time, Dr. Joel Wallach.

And he was there during the summer and he said, “Oh, we’ve got this program that we can get you on this grant for the summer.” And so that was my first introduction to zoos, and even thinking of zoos as a potential career.

So Dr. Wallach interviewed you for the summer job?

He interviewed me, but it was a pretty much, “Oh my gosh, we’ve got somebody who’s interested, and let’s get him in here.” And so his position was not treating the animals at the zoo. It was a, he was under a research grant that paid him to do pathology on the animals that died at the zoo. And he was looking for actually any animal that might have something that could be used as a comparative pathology to human medicine, of how this animal, any animals could be potential research animals for human medicine. So you were gonna work for him, or- I was working under that grant, doing different things that, assisting with the necropsies or autopsies on the animals here.

Now, at the time, there was a veterinarian at the zoo, aside from Dr. Wallach?

The zoo did not have a full-time veterinarian. The zoo had a part-time veterinarian, Dr. Alfred Mohler, who I never saw, because he never came out to the zoo. It was interesting, the zoo had a contract with him, but he was never there the whole summer. They just didn’t have very much veterinary care at that point, it seemed like. They would occasionally, if they had something, Joel, Dr. Wallach, would make a mention, “Well, we might be able to do this.” So he would give them suggestions as what to do, but that was about it. So this is, now you’re going to the University of Missouri- Correct.

That’s around 1968?

I was in a veterinary school from ’66 to ’70. I got my doctorate in 1970.

And what did Dr. Barry Commoner have to do?

Did he have anything to do with- Dr. Barry Commoner was the professor that actually got the huge grant, a comparative medicine grant. He was with Washington University, and Dr. Wallach was hired as part of that grant, and my summer, I got paid by that grant.

Now you, that was a summer job?

Yes. And then you went back again as soon as- Went back to veterinary school.

Why did you go back again?

What, oh you mean, why did I go back to the zoo?

Well it was a summer job, and I was assisting with the pathology essentially. Under the same grant. The first summer, between second and third year of veterinary school, but then I went back to veterinary school for that, in the fall. And then I had the summer off between third and fourth year, but I wanted to get more practical experience of really treating animals, not just dissecting animals after they’d, you know, passed away. So I got a job that summer working at the Humane Society. Humane Society of Missouri is a big operation in St. Louis, with the 10 or 12 veterinarians that do surgery, treat animals, they have a regular clinic there. And I got very good practical experience of treating animals and doing surgery there. But Joel Wallach had left the St. Louis Zoo, so he was no longer there, and had actually gone to the Brookfield Zoo as an assistant director.

And that meant there was no veterinarian there. Dr. Alfred Mohler was probably still on call, but wasn’t going out to the zoo. So I went to the zoo and I said, “Look, I can get off three afternoons a week and come over, and at least continue doing pathology for you.” And so I did do that.

Who were you talking to?

Who was the, were you talking to the director- Bill Hoff was the director at the time. Actually, Marlin Perkins was the director, but Bill Hoff was the assistant director. And Marlin Perkins was the director, but he was also doing a lot of filming for “Wild Kingdom”, so Bill Hoff kind of was the one that I talked to about doing that.

So did you have, just ’cause you mentioned Marlin, did you ever have the opportunity to meet Marlin?

Did he come out to the base- Oh sure, no, no Marlin was a very, very, a very gentle person. I always enjoyed visiting with him, very humble person. So okay, so now you’re saying, “I can help you couple days a week doing pathology,” and you’re saying this to Bill Hoff.

After that summer doing this, and then you graduate, right?

Were you thinking, “Hey, I wanna work in a zoo,” or were you just trying to get a job somewhere?

No, no, at that point, after being there for those two summers, you know, it kinda got in my blood, I guess. It was like, “Wow, this is really interesting.” You know, it was challenging, it was fun. It was something that, “Yeah, I could do this,” I thought. And so I talked, I said I would be interested, and so Bill Hoff offered me the job. This was before I graduated, you know. He said, “Yeah, we can hire you as our full-time zoo veterinarian.” And then I got to thinking, “Well, you know, I’m just not even outta school yet and they’re offering me the job. There must be something that, you know, this is just unheard of today,” that never happened. I said, “There must be something wrong with this job.

I better check this all out.” So I talked to some other individuals who, you know, in the community, I said, “Well, why aren’t they offering this to somebody with a lot more experience and everything?” And they said, “Well you know, veterinary medicine in zoos, there just weren’t very many zoo veterinarians, and they don’t know a whole lot about it.” At that point, they didn’t have a lot of the anesthetics that today we have, and so, veterinary medicine in the zoo just was at its infancy, you know, it was just starting. You were kind of at the ground level there when you first started.

And that was 1970?

is when I started full time at the zoo.

And do you remember your first day in the job?

(laughing) I always remember the first day, because the Kodiak bears had got into a big fight, and one of them was bleeding and had a huge laceration on its foot, you know. And so that was my first big deal of treating any animals at the zoo. And so you know, in veterinary school they don’t teach you a whole lot about zoo animals, and they don’t teach you anything about using a capture gun. And so I went out behind the hospital and used the capture gun, to make sure I could hit the target, shot at a target for a little while, ’cause I was gonna have to dart the bear, and we got the bear in the back. We always bring the animals out of the exhibit into the back area, to be able to treat it. And of course, since I was new there, the keepers were there who normally take care of them, the curators and even the director came down. Everybody wanted to see how their new veterinarian was going to be on the job, I guess. They were very helpful.

You know, at that time we were using a product called M99 or etorphine to immobilize animals. That was relatively new at the time. It had been used, and used on bears. And so we loaded up the darts with the capture gun, and they were again, very helpful, showing me how to load the darts, and what. And the darts of course come in various sizes. You’d guess about the animal’s weight, and dose of how much you should use on it, and put it in the dart. It goes into the dart, you put a needle on the front, that can be various sizes. Some of them have barbs on them, some of them are just, are straight.

Then you have the plunger behind it and the charge and the tail piece, and all that goes into the gun, and then you dart the animal. Well, I loaded it up, of a dose that we thought oughta work on it, and I used a one-inch needle on it. It had a barb on it. I was able to shoot the bear, hit the bear where I wanted it to, and I know it hit the bear ’cause the dart was still sticking in there. I assumed that the charge went off. However, the bear didn’t get immobilized, he was still walking around. 10 minutes go by, 20 minutes go by, by this time the bear should start seeing some of the effects, but it wasn’t seeing anything. So everybody’s trying to offer advice.

So we loaded up another dart, figured, well maybe it hit him, but maybe it didn’t go off, maybe it didn’t fire. And so this time loaded up a two-inch needle on the end, and again, another dose of the M99 and hit the bear, then again a second time. Oh, within about eight, 10 minutes I guess, the bear goes down, becomes immobilized. And so we can get in there, clean up the wound. I mean it was a, you know, gosh, the whole bottom of the foot was covered with this laceration. Had to be a couple inches deep and bleeding, and got it all closed and sutured up. After we were finished doing that, it cleaned up, looked pretty good, started putting the bandage on there. And you know, because in veterinary school we’re learning, well, you gotta keep that wound clean, and so that’s the only way.

And and of course they, the keepers and so forth were offering me advice and said, “You know, there’s no use putting a bandage on there. He’s gonna tear that off immediately.” Well, I guess I was a little stubborn and I continued to put more gauze and tape on there. Continue, well they just, “You’re wasting your time putting that on there.” And the more they insisted about not doing it, the more bandage, I guess I wrapped on there. So by the time we were finished, we had a good-size bandage on there. Well, after we were done with all that, and I was satisfied that it was clean, had everybody get out of the enclosure. An M99 has a specific antagonist, that you give it intravenously and it reverses the M99 and the bear wakes up, so at least I was hoping it was gonna wake up. And we all got out, I gave it intravenously and got outta there, and the bear kinda got up and walked around a little bit, was still pretty groggy, and moved around. But he was up and moving.

Well, five days later that bandage was still on the bear. They couldn’t believe it, they couldn’t understand why. You know, “Nobody is able to put a bandage on a bear that stays that long.” Well, I didn’t know what happened at the time, but what actually happened, bears have a heavy hair coat, a thick, heavy fat layer. Well, any medication that goes into the fat layer is released very slowly into the system. The first dart that I used was a sharp needle, and so that drug got into the bear, but it was in the fat layer. The second dart with the longer needle went into the muscle and actually immobilized the bear. However, that first one went in there and kept releasing in the fat layer for the next five days, and kept that bear kind of tranquilized a little bit for it, and so some things turn out fairly well. (chuckling) They still think I’m the best guy at putting bandages on an animal. Made your reputation.

Now you’d mentioned the director came down.

Who was that?

Bill Hoff was the director. He was the director. Marlin had retired and Bill Hoff was the director at the time.

Okay, what was the zoo like, that you started there in 1970?

What was the collection like, what type of zoo was it?

It was a zoo, what you would call a taxonomic collection. I mean, we had bears in one area. We had the big cats in another area. The hoofstock were all together, the birds were together. So it was based on taxonomy, but it was a well-rounded collection. We had, you know, a reptile collection, huge reptile house, and primate collection, small primates, great apes. It was a well-represented animal collection. The majority of the keepers were men.

There were only a few women keepers in the children’s area. And a lot of the keepers were old timers, men who’d been there, some of them for years, but really pretty good animal handlers. And it was, in the beginning, you know, I learned a lot from them, and that was my attitude. “I need to learn from them as much as they can learn from me.” And so, you know, when I worked the summers at Monsanto prior to that, at the chemical plant, I was working with a lot of older men at that time. And so I knew how to work fairly well with them, and so it was a good opportunity.

What was your biggest concern when you first started working at the zoo?

Well, it was challenging. I mean, it was difficult, because you didn’t learn about zoo medicine in vet school. I mean, you learned medicine, but you were applying things that you’d learned for domestic animals on different kinda animals, and they weren’t always the same. The anatomy wasn’t always the same. A lot of the physiology’s the same, but the immobilization and anesthesia and restraint were certainly completely different. So you know, when I first went to the zoo, when I took the job I thought, I was gonna make sure I gave a good shot at it. Because I had heard, and I’d seen actually, even with Dr. Wallach or whatever that you know, a lot of the zoo people, they don’t want some veterinarian coming in there and telling them what to do. They’ve been doing all this all their years, and they didn’t want a university educated person coming in and doing all this.

So I was a little skeptical, and was careful about how to deal with that. And like I said, I wanted to learn as much from them, but I thought, “I’m gonna stay at least two years. I’m gonna do, you know, give it a good shot, and see how it works out.” Well, 37 years later I was still there. (laughing) So when you first started, you were the first full-time veterinarian. First full-time veterinarian. And your responsibilities were narrow, or- Yes, it was strictly clinical care of the animals.

Whom did you work with?

Did you have a staff of people in your department who were helping you, or was it just you?

Well, I was the only veterinarian, but since Washington University, who had that grant, you mentioned Barry Commoner, that was still going on. They didn’t hire a veterinarian, but they still had a couple of staff people. There was two technicians that were, one was a histology technician, made the slides for pathology, because that was part of the job too, was also doing the pathology, the necropsies on all the animals, and so there was assistance there. But in terms of the animal division, you know, there were curators who, and keepers.

But from the veterinary standpoint, that division, department, it was you, and you did the pathology also?

Yes, yes, did all the the necropsies on animals. Yes, and made all the reports.

When you first started, were there issues that you were aware of that St. Louis Zoo was facing, or anything that was going on that the zoo was involved with, other than veterinary medicine that touched you, or you were aware of?

Well, I mean I was, as a new recent graduate veterinarian, I was still learning, you know, veterinary medicine. And one other thing that I did continue to do, one thing that I worked out with the director was, I said, “Look, I’m here all, you know, every day, and then I’m available on Saturdays and Sundays,” ’cause I was off on those days. But in veterinary school, you learn the techniques, but your surgery skills are not up to par just yet. You know, you’ve done surgery in class, but to be a good surgeon, you have to have a lot of experience, I think. And I had started doing that at the Humane Society, and they do a lot of surgeries every day. Not only, you know, spays and neuters, but they also had a lot of other types of surgeries there, a lot of orthopedic work, and everything that was done. And I said, “Look, I can go over at least one afternoon a week and hone my sur surgery skills there, and that will be helpful for me, but also helpful for the zoo when surgery has to be done.” And so I continued to do that, and really, I thought, developed my surgical skills over there.

You were on call?

As a veterinarian?

Did they call you at late at night, the zoo?

Did people work at the zoo at night to- Very seldom was there any calls at night, because the keepers weren’t there at nighttime. There were night security, but their responsibilities were not really so much animal care. But, so seldom did I get calls at night, but always on the weekends, there would be something.

Did you start to develop a philosophy of working with the curators and the keepers?

You indicated, you know, sometimes they don’t like the university guy coming in, telling them what to do, but you had a job to do.

Did you start to develop a philosophy about working with all these different groups who you had to depend upon?

Well, I had to depend upon them. Certainly they’re the ones who, you know, are with the animals all day, and they know if their animal isn’t acting properly. And so I, like I said, I tried to learn a lot from them, but I also tried to help them. And you know, if I was doing a necropsy on an animal, I brought the keeper up and I said, “Look, you know, okay here, and this is,” you know, just going through some of the anatomy with them even. You know, and you open up and you see the lungs, and the lungs are all deteriorated, well you know hat that animal must have shown, seen some signs before that.

And talk to the keeper, “Well, was he having difficulty breathing?

You know, did he have any discharge coming out of his nostrils,” or what have you. And so I think that the keepers enjoyed learning more about the animals as well. And I think as a result of that, it did help have a good relationship between the keepers and myself, and they would see things early on that they would not have seen otherwise.

Was that same philosophy of working with the curatorial staff?

Yes, yeah curatorial staff, same way, because they, you know at that time there was a number of young curators, zoologists, different titles to it. But Charlie Hoessle was a curator in charge of all the reptiles, also he oversaw the education department, but he was curator of herps. Bob Frou was curator of mammals and did all hoofstock, but also primates and elephants and so on. And actually a guy named Mike Flieg was curator of birds at the time.

Were there other, among the zookeepers that you learned from, were there any people that you would call characters?

(laughing) Well I don’t know about the curators as much, but you know, the zoo still had three animal shows at the time. And so there was the trainers who did the animal shows. Now at that point, one of the trainers who did the big cats, his name was Jules Jacot, and by that time Jules was getting up in years. And I don’t know that he was absent-minded, but you don’t want somebody who’s taking care of big cats to forget things and forget locks, or whatever. But Jules was a tough old bird that, he was a character. We had a guy who did the chimpanzee shows, and they were all interesting individuals to work with, very knowledgeable of animal behavior to be able to be as good of trainers as they were. But so yeah, there were some interesting individuals.

What experiences might you have had in those formative years that may have changed your notion, if you had one, of what a zoo should be like?

Well, I think at that time zoos were primarily places where people came to be entertained, to have a good time. I don’t think at that point conservation was a high priority for most zoos.

Working with the curators and keepers, it was, you know, what’s best for the animals, how do we take care of them Well, and in some cases, how are we able to reproduce them?

And as you’re doing this job as a veterinarian, did you think you wanted to do more than that, or were you thinking, “I want to be a veterinarian here,” and maybe now you’re thinking, at what time did you think, “I think I wanna stick around here”?

As a veterinarian, and as a veterinarian in really the pioneer days of veterinary medicine in zoos, it was a huge opportunity to learn more. And so besides just treating the animals, and you know, for their medical care, I thought there was a big opportunity for, I don’t know whether you wanna call it research, but certainly learning more about the animals. And so I got really more involved with veterinarians from other, there were very few of us who were full-time veterinarians for zoos.

And it was a group that if you had cases, “Well, how do you take care of this?

How do you take care of that?” And so we communicated a lot, and so I got involved probably a little bit more in some case studies, and publishing some of the events, some of the cases that I saw. And so I got more involved in research activities, and learning more about the animals that we had there. Tell me about the people. You mentioned the zoo veterinarian community was rather small.

Who were some of the people and zoos who had the full-time vets that you were working with?

Well, Chuck Sedgwick was at San Diego Zoo. Earl Schobert was not full-time, but he did Busch Gardens in Florida. The other ones that were, I talked with Paul Chaffee out in California, Gordy Hubble down in Florida. There was a couple of part-time ones. Bud Herzog was part-time veterinarian at the Kansas City Zoo, and fairly close by. Jerry Thiebald was part-time veterinarian at Cincinnati Zoo. Those were ones that I would meet with. And then I always, I got involved in the Zoo Veterinary Medical Association, which was really just at its infancy then.

So how did you communicate these different cases with these veterinarians?

Well, if they were extremely well worked up, I could go, you know, publish them in various journals, referee journals. You know it was interesting, because as you know, university professors and so forth, they talk about publishing all the time, or trying to publish and how difficult it is. It wasn’t that difficult for me, because there was so many new things coming that nobody had ever seen before, or if they had seen them, they hadn’t written about it or published anything about it. So I had the opportunity to publish numerous articles every year in referee journals, which just isn’t heard of very often.

What prompted you, if there was anything, to feel that it was important for you to publish, and tell people about what you’d seen?

I guess I just thought it was part of the duty to share that knowledge and to do it in, you know, a professional manner. Every time I did I, you know, took that opportunity. I also did, you know in the beginning, offered an opportunity for veterinary students who wanted to learn about zoo medicine, almost you know, after being there a year or so, I allowed veterinary students to come and do a, whether you wanna call it a preceptorship or a short-term time with me to learn about it. And I always encouraged them to follow up on it, to keep, you know, information and publish it.

So you’re the veterinarian, and while you were the veterinarian, is that when you started the preceptor, the residency program?

Or was it when you got to the next level and became the senior veterinarian?

Did you start this program as you were the veterinarian at the zoo or after you moved up a little?

As I was the veterinarian at the zoo, I right away allowed veterinary students, I had them sign up, I only took one student at a time, and they were there for two months, and then another student. At that time, the university had started what they called the block system, where they did two months of surgery, then two months of small animal medicine, two months of theriogenology and so forth. So I kind of tied in with that at the university so they could come for two months and do it, and then another student for two months. And so I started taking mostly students from the University of Missouri at first. But as the times went on, they came from all over, the US mostly.

So this was your idea to start the program?

Yes. to the zoo director, and you had to sell it to the university. Well, I had to sell it to the zoo director because it allowed, but these students weren’t getting paid. They were coming to learn. And so in the beginning yes, I had to sell it to the zoo, to allow somebody else to come in that was gonna be following me around, so to speak. And, but you know, they were okay with that. And the university was fine because they didn’t have anybody else who could teach anything about zoo medicine, and so they were okay with it.

Do you think you did it because you never had the opportunity?

(laughing) Maybe, you know?

In a way I did have the opportunity though, because I did get there, it was under a different thing, and it wasn’t doing clinical medicine, it was doing pathology. But it gave me the opportunity, and so maybe that’s why I did it, I don’t know. I just thought it was an important thing to do.

When are you approached to get a different position than just veterinarian and why?

I mean, I don’t know that I was approached to do it. I guess as doing clinical medicine, I was always interested in why something works or doesn’t work I guess, and that’s research in a way. You know, you’re checking into it.

Well, what drugs are we using?

Because essentially as a zoo veterinarian back then, we were doing research. I mean, we were using drugs on animals that had, those drugs had never been used on a lot of those animals. We talk about M99, well the other anesthetic that was used a lot back then was sernaline, and then ketamine came on and well, it hadn’t been used on most zoo animals.

And so we had the opportunity, and you didn’t necessarily know, well, what dose do you use on an alligator?

What dose do you use on, you know, a lemur or whatever?

And trying to figure it out was sometimes a little difficult. But you became senior veterinarian and director of research.

That’s another position, or you just evolved into it?

I just evolved into that, because as we took veterinary students for two-month blocks along, then that evolved into setting up a residency program, which is for a veterinarian who has graduated from veterinary school already, and wants to devote his career to zoo medicine. So that’s something that we started in about 1974. So I was at the zoo for maybe four years by that time. And that I did have to sell to the director and to the university because that was a paid position. It was paid by the zoo to the university. The resident got paid by the university, got their paycheck there, but the zoo deposited that there. We set it up that way. It was the first residency that was zoo-based.

There was a veterinary residency prior to that at University of California, but that was university-based. This had the zoo there, and I wanted it to be part, really the university to be part of it, just like any other resident. If somebody’s doing a residency in ophthalmology or surgery or whatever from the university, they have certain requirements that they have to meet, and certain publishing requirements and so on, and I wanted our resident to do the same. So yeah, that was a bit of, by that time, a different director was there, Bob Briggs was the director. And Bob, when I talked to him about it, was excited to proceed with it. And he and I, and Charlie Hoessle at the time, went down to the university and talked to the dean, and see if we could get that going, and we did. And so we started the residency there.

And that was the first type of thing for the medical school?

First zoo residency for the veterinary school, and also of course, the first one that was zoo-based in the country.

So now you have a resident and yourself, so that made you the senior veterinarian?

Well, (laughing) I guess that would’ve, but essentially the other was a residency, and we went through two or three residents, and they came for two years and then they moved on. The first one went on to Minnesota Zoo, and then the next one went on to another, and then you know, to different zoos. And I mean, I think we trained them well, and then I kinda said, “Well, maybe we need a second veterinarian at the zoo, instead of just a resident.” And so we stopped, we used some of that funding to hire a second veterinarian, and didn’t have the residency program for a while, and then came back to doing that. So I guess that’s when I became senior veterinarian.

So was that again another sell, to say, “We need a full-time vet here”?

Yeah sure, yeah.

And who became the junior to your senior?

Who was the first veterinarian that you hired?

That was Eric Miller. Eric Miller had done a residency, and then was the junior veterinarian, I guess you would’ve call him then.

And you mentioned there was a new director at the time, William, Bill Bridges?

Bill Hoff was the director that I worked under first, and then Bob Briggs was director after Bill Hoff.

Now was Bob Briggs a zoo man?

No, Bob Briggs was, he was a PR guy. At that time, well step back a little bit as far as zoo history, the zoo was part of the city of St. Louis. The St. Louis Zoo has always been completely independent of politics. It’s run by the zoo board, but those board members were appointed by the mayor, so there was still some connection. But the zoo was supported by a mill tax, a property tax, from the city of St. Louis. At that time, back in the early 1970s, the city of St. Louis is surrounded by St. Louis County. It’s two separate entities. And the population was moving, like many metropolitan areas, from the city to the county, and a lot of the wealth was moving with that.

And so property taxes in the city and county were pretty much on an equal level. We had a board member who, actually we had a number of board members that got involved with this, to create what’s called the Zoo Museum District. And the zoo and the art museum, both institutions that are in Forest Park, were supported by a property tax on all the property in the city of St. Louis. Well, they wanted to create a Zoo Museum District to include a property tax not only in the city, but also in St. Louis County, which would if passed, would double the tax base for the zoo and the art museum. So, but there were three institutions, the zoo, the art museum, and the science center. The science center was located in the county, and so that’s why they called it the Zoo Museum District. And so in ’72 we were very active in trying to create this Zoo Museum District. We had a board member who was very high up in, you know, was connected to the Republican Party.

We had one that was connected to the Democratic Party. They worked together with the legislature, ’cause it had to be, this was something now that went to the state legislature to approve it, to create this, and then it had to go on the ballot in the city and the county to be voted on, to see if they would agree to be taxed, the county. Overwhelmingly it passed, and each one is separate. Both the zoo and the art museum and the science center all passed, and so that created this Zoo Museum District. Later on in history, the Botanical Garden and the History Museum also are part of that now. But in the beginning, that created the Zoo Museum District. And at that time there was a PR firm that was hired to do all of the maneuvering for a tax levy like that, and Bob Briggs was the guy that was from the PR firm. And so the zoo was so impressed with him, when Bill Hoff left, they hired Bob Briggs as the new director.

He had no animal experience whatsoever, but he was great at PR and a good manager. And he relied on Charlie Hoessle, who at that point had become general curator, was no longer just curator of reptiles, was general curator, and really has Charlie to run the animal portion of the zoo. He had somebody else who did finance and so on. So he was the director, but relied on the rest of us, and myself for veterinary and research aspects of the zoo.

Did the people at the zoo, the curatorial staff, the veterinary group, did they think, “Hmm, what’s gonna happen here, we don’t have a zoo person?” Or was there any pushback?

I think there might have been a little bit, but since they knew that Charlie was the person in charge of really running the animal portion of the zoo, Charlie didn’t have the title, but he was essentially assistant director. I mean, he was the one who called the shots. Bob Briggs did not try to interfere or manage anything as far as the animal collection was concerned. Charlie ran that.

Now that you’re the senior veterinarian, what was a typical day?

Were you still just treating the animals and, or you had help now. Well, we’re still treating the animals, still doing a lot of the clinical work, but also publishing and trying to do various research, and training I guess always, I was always training people. And you talked about the research initiatives that you’re now responsible for. A job they didn’t give you, but you kinda took it on.

Could you talk about some of those initiatives, like the tissue bank?

The tissue bank was something that actually had been started way back with Joel Wallach, and Barry Commoner, I guess. I mean that was part of the initial grant, which of course by this time had run out. But I felt it was a valuable thing to do, and we continued to do that. And we call it a tissue bank because what we would do, and we would save, when we were necropsing the animals, we would save various tissues, sections, you know, liver, kidneys, spleen, hypothalamus, whatever. And we would put these tissues, we saved them either fixed in formalin or frozen. And then we would put essentially a catalog together, and we would send that out to any researcher, and you know, was available to any university or any research institution. National Cancer Institute, all these places would get the catalog and say, “These tissues are available for free. All you have to do is pay for some of the shipment, and so forth.” We would be doing the collecting and the storing of them, and make them available.

And if you had particular requirements, if you wanted certain things to be saved, looking for answers for medical problems for people. You know, the National Cancer Institute utilized a lot of the tissues there, and we started saving. “Oh, how do you want it saved, what do you want?” Like I mentioned hypothalamus, ’cause that’s a little bit more difficult to be saving that from various species, than just taking a section of liver, kidneys or what have you. And so we would continue to save those tissues and make them available to the research communities.

You did some research also then in reproduction?

We did a lot of reproduction research. Initially, I think zoos are a little bit hesitant to say, “Well, we’re gonna do research on our animals.” I mean, that’s not kinda just accepted, and it’s like, “But well, wait a minute. We’re gonna do research on reproduction so, because there’s a lot of species that are not reproducing and why aren’t they, and what can we do to help that?” And so reproductive research and behavioral research are probably the two easiest things to introduce, you know, if you’re going to be doing any research at all. Or research on, you know, necropsy or pathology, that’s okay too. But, so reproductive research, and at that time we had, when I started doing a lot more of that, we had one of the curators at that point who had joined the staff, was Bruce Reed, and he was a graduate from the University of Missouri Ag School, and was very familiar with a reproductive physiologist at the university who used to come down. So primarily we did reproductive research in terms of a lot of semen collection, and that was probably the biggest thing, and working towards artificial insemination with mostly hoofed animals, but we did it with a lot of other species too.

So the zoo was looking for grants, getting grants, bringing people in, or it was in house?

A lot of it was in house. We would always, if there was grants available, we would work on those. But we didn’t have a whole lot of time to put granting applications together.

And one of your other research things was anesthetics?

What were you doing with that and why?

Well again, the big difference with zoo medicine compared to I think, domestic animal medicine is that you’re usually always anesthetizing the animal. You’re immobilizing the animal, I guess. Difference being immobilizing is keeping it so that you could do something to it. Anesthetizing means that it’s not gonna have any feeling either, it’s not going to feel it, as opposed to an immobilization, well they can’t do anything, but they still feel it. And so, you know again, anesthetics or these various immobilizing drugs hadn’t been used on all species, so figuring out the correct dosage was important. But then there’s, one of the bigger ones was a product called, CI-744 was the experimental name. Parke-Davis was the company at that time that had that available. And so I was able to get the product, it was not marketed yet at that time.

And so CI-744 was, today it’s on the market as a product called Tilazol. But at that time it was extremely valuable immobilizing so many different species that really went down well, and after you were finished with your procedure, recovered well. So it did not have a specific antagonist, but it gave a good plane of anesthesia. So you were using this new drug on your zoo subjects as you needed to. Yes.

And publishing those details, or doing, what was going on then? You were?

Well yes, part of the arrangement with the drug company, they provided the drug, but I had to always provide a sheet, you know, “Well, how long did it take to become immobilized?

What was the plane of anesthesia?

How much, what dosage did you use?” And so forth. And that had to get sent back to the company all the time to get more of the product. Maybe what you’re referring to is, at one point, it just was such a fabulous drug, except I used it on one species and it didn’t work so well, and that was on a tiger. For whatever reason, CI-744 is not a good immobilizing drug to use on tigers. And so the tiger became immobilized fine, but it didn’t recover real well. And so when that happened the first time, you know again, when you’re immobilizing a tiger, you’re with a dart gun. There can be other problems with it.

You know, why didn’t the animal, why is the animal now having ataxia?

It’s not using its hind legs very well. I thought, well maybe the dart hit, kinda on a spinal column, or up there, and it you know, caused some difficulty there, and why it’s having difficulty in the back legs. And so I thought, “Well, we’d better go in and immobilize that animal again. So again, I used CI-744 again and I had, we just had difficulty with the tigers. And so I started contacting other veterinarians that I knew at the time who were using the CI-744. “Was there a problem with it? Was there,” you know, and some of them, one another who had used it on tiger said, “Yeah, the tiger just didn’t do as well as everything else.” And it was really interesting, because I had difficulty then getting any more of the product from Parke-Davis Company. They weren’t sending it to me. And I realized that probably they weren’t sending it to me because they knew I had had some issues with it, with tigers, and they thought maybe I was gonna publish something about it.

And, you know, I told them, “Look, I don’t wanna publish anything about the tigers, the drug is fabulous.” And at that time they were getting ready to put it on the market for use in dogs and cats, not in, obviously the zoo market is not a big place for them to sell a whole lot of product, and they didn’t want anything come out that would be detrimental to the drug. And so I at that point said I would not publish anything about tigers. And it was kind of at that point for me, it was like, “Hmm that’s,” I thought it was important to do it. And later on somebody else did publish about it, that you shouldn’t use it in tigers. But I continued to get the drug, and it was a fabulous product. Were you still using the Palmer- Capture gun. Or were those also evolving into different- Well the Palmer capture gun, which is the one that I talked about, that has the various needles and various things, and uses a little charge that forces the plunger down the tube, allows you to project any liquid medication into the animal. Whether you’re anesthetizing the animal, whether you’re just giving it antibiotics, whether you’re giving it a vaccine, any liquid medication can be delivered intermuscularly into the animal.

However, the dart’s a pretty good size, and it hits with some impact. It’s fine for a large animal, but a small animal, it’s a little bit, can be tough. At the time we made some darts, we’d seen some that somebody had had put together using the plastic disposable syringes, using a needle. And so we did a lot of stuff trying to make our own needles, our own darts, that instead of firing out of a gun, we used a blow pipe, and we could take a plastic syringe, modify it in such a way that you would have a plunger on it. And in the beginning, what we would fill in the back was butane from butane lighters, and then we would put the liquid in the front, and then we’d put a needle on it and we would modify that needle by plugging up the front, putting a hole in the side of the needle and putting something on there, so that when that slid down, the medication would be injected into the animal. And so yeah, we played around with a lot of that, and used blow pipes to project those in. Today that whole product, I guess you’d call it, Teal Inject is a company that makes those for you now that allows you to use, and it’s a much lighter dart, so you can hit an animal that’s, you know, five, 10 pounds and you’re not gonna damage it with the Palmer capture darts, you know, can cause some trouble with them.

Were you, or were you in St. Louis, one of the leaders in doing this kind of research?

Or were this being done in other zoos also?

Oh, I think this was being done in other zoos too.

Yeah, everybody was looking at, you know, what can we do that that is better?

Now you have, we talked about publishing extensively and you have published extensively. Can you relate how you came to be the co-author with the gentleman you talked about earlier, Dr. Joel Wallach, with a book called “Diseases of Exotic Animals”, which is a pretty heavy tome.

How did that come about?

I got called by Saunders Publishing Company, wanted me to be co-author of this book, and it had been in the works for several years. They had put a team together of about 20 or 30 different authors, each of them had different sections to do. One of them would be doing elephants, one would be doing hoofstock, one would be doing primates, one would be doing marsupials and so forth. And all of these authors were to do their section for Saunders because there were no, really any texts on zoo medicine. And one by one the authors, these were usually veterinarians or in zoos or others of university, whatever. One by one the authors wouldn’t meet their deadlines, and they, you know, would kinda drop out. And at each time, Joel Wallach was doing more of it. He said, “Well, I can do that also.

I’ll do marsupials as well as doing primates, and I’ll do this,” and so forth. And one by one it got down to where there was only three authors left. Joel Wallach doing all of mammals, Bob Altman doing birds, and then I’ll think of his name, who did reptiles. So there were three of them left, and they were putting it all together. Well, they would each put their chapters together, and then they would send the galleys or texts to the other authors to review, and kind of go back and forth. Well, there’s a way of being an editor, of looking at somebody’s writings and saying, “Well you know, I don’t agree with this,” or you know, “Can this be worded in a different way or something,” as opposed to saying, you know, “This is a pile of crap.

This is no good, you know, this is terrible,” you know?

And so apparently the three together were having all kinds of difficulties. And Saunders, who published all kinds of medical textbooks, realized this just wasn’t gonna work. And at that point, Bob Altman said, “The heck with it, I’m going to publish my, I can do books by myself,” and same happened with the reptiles, and he went and published it separately, and so it was just Joel Wallach left. And at that point, Joel was no longer in the zoo business, and so they felt he didn’t have the, I guess credentials to be able to do it. And they talked, but he really was a brilliant person and very good, published a lot of stuff. And they went to Joel and said, “You have to have another co-author, and who would you be able to work with?” And Joel is a brilliant individual, but maybe doesn’t have the best personal skills sometimes. And so he, for whatever reason, he had worked with me when I was a student and he put my name down. And I hesitated a lot.

Again, I went to a lot of other individuals asked, “Well, what do you think about me doing this?” ‘Cause this was 1983, and I was, you know, well known in the zoo business at that point, and knew a lot of people to talk to. And everybody said, “You’ll never be able to do it. You won’t be able to work with Joel. I mean he’s just, you know, you can’t.” Says, “He’s brilliant, he’s the smartest guy almost, you know, around. But you just aren’t gonna be able to do it.” And I, “Well, I’ll see.” I knew that I knew Joel and I like him, and I thought, “Well, I can work with Joel.” And so I went, I said to Saunders, I said, “Let me see a couple of them.” And so they had a couple of the chapters already started, and I went through them, and there was a lot of stuff in there. For instance, the one on primates. Joel must have a photographic memory because he just, he knows, I mean he is just very bright, but maybe doesn’t, it’s all in there, but he doesn’t have it very well organized. So when he was talking about anesthetizing or immobilizing primates, he had a whole section using ketamine, which is the drug of choice for immobilizing primates at that time.

I guess maybe Tilazol maybe is better now, I don’t know. But ketamine, he had that, he had, you know, a page on that, and then he had a whole page on using M99, and then a whole page on using, you know, various other inhalant anesthetics and so forth. Well, this text is supposed to be for people, especially veterinarians to use, you wanna pinpoint the drug of choice, which is ketamine. And so I took what he had written about ketamine and elaborated about that, and went into much more detail about using ketamine, because it is certainly the drug of choice. And then, yes, mention M99 and talk about that. There may be some applications where you need to immediately wake up the animal, because ketamine, they wake up slowly. And if you’re gonna put it back into the wild where other animals could hurt it, or if this was in a cage or enclosure, where you had other animals in with it, you may need to have, so there may be some cases where M09 would be used, but I would say, better than 90% of the times you want to use ketamine. You don’t want to be using M99 on it.

I mean, I mentioned earlier my experience with the M99 with the bears, it’s not the drug of choice for bears at all, but that’s what was used back then.

And so I was able to take what Joel had put together and modify it and make it really useful for the practicing veterinarian, and I was able to do it in a way that I think Joel was accepting of it, instead of, “Well, you’re changing what I put down,” you know?

And so it worked out, and we were able to put it together.

Is that, if you know, do you think it’s still being used today?

I think it is still being used today. I think it was a very worthwhile text. I know it was used in veterinary schools. I will say for me, it was a, I don’t like writing. You know I published a bunch, but I don’t like doing it. And it was so taxing on me, I have hardly published anything since then. You know it just was, it took it all outta me at that time. Now, during your time as veterinarian, slash senior veterinarian, I would suspect that there are some memorable events, such as animal escapes, that you had to deal with.

And can you talk about some, so for example, like the rhinoceros escape?

The rhinoceros escape, and most animal escapes, people think of animal escapes as getting out and running around the city, or whatever. They get out of their enclosure, but they’re not out of their building usually, and they’re not out of their, you know, usually. The rhino, I assume that the keeper must have left the lock off the front of the enclosure. The rhino area, there’s outside yards, there’s inside enclosure, and that inside building is open to the public, so there’s a rail that keeps the public back from the bars of the enclosure. And the rhino had gotten out of his enclosure, but was between the enclosures and the front rail that keeps the people back. A little space, maybe four, five feet wide. And it had gotten out of there and was still behind that little rail, only three foot high, and just sleeping in that area in the middle of the night. The security guard of course saw that and immediately called, and the curators are there, keepers, and of course I was in.

It was about 3:00 in the morning, And, what are we gonna do, you know,?

We can dart it. I mean, it’s just sleeping there. I could even almost reach over and just give it a hand injection of something.

But now, how are we gonna pick up this, you know, three, 4000-pound animal and get it back in its enclosure?

We can’t get a forklift in there. We can’t get anything in there, and what do we, so fortunately there was a trash dumpster that was right next to it. We’d kinda wake the rhino up and behind the trash dumpster, push, push, get him a little bit further, and he’d go back to sleep. And you know, it took us about three hours, but we got him all the way back to where the only way he could turn would be back into his enclosure. So we didn’t have to immobilize him or do anything to get him back in. But you know, it was something that you’d think, you know, we certainly didn’t wanna anesthetize him at that point, and try to get him back in. But you have had other escapes, that as veterinarian you’ve had to deal with. Fortunately, none of them real serious.

We had one Barbary sheep that actually did get out of the zoo grounds, and was running around Forest Park, a large 2000-acre park, which our security was following, or was going, and I was in their truck, you know, chasing it all across the golf courses and so forth. And really probably should not have been driving across some of the greens or whatever, but we eventually were able to dart that animal, and get it back to the zoo.

Do these things sometimes happen late at night, or mostly during when keepers are there?

Well, that one was during the day. I think most of them were during the day, not late at night.

Did you ever have anybody call you with an animal escape where your reaction was, “Oh my God”?

Fortunately we have not had any, you know, serious. I mean like that Barbary sheep out, you know, it’s not gonna injure anybody. It’s not like a big cat or you know, a bear or something that could, or some of the primates, that could be potential damage to visitors or to people. We’ve not had to deal with that, we’ve been very lucky. You mentioned before that you were a charter member of the American College of Zoological Medicine.

Could you tell us a little more about getting that process off the ground, and what does board certification mean?

To be board certified in a particular specialty of, whether it’s human medicine or veterinary medicine, you know, you’re board certified as a ophthalmologist, as a obstetrician, as a you know, surgeon, whatever. And so there was no board certification for zoo medicine, and that was something that had to be put together to the American Veterinary Medical Association.

And Murray Fowler was the one who really spearheaded that, and was most instrumental in getting that off the ground, and starting way back in about 1980, was gathering who would the professionals be, who would be considered the chart of diplomats?

And then once that’s done, others could become board certified by meeting certain qualifications and then going through testing to do that. And so I was fortunate to be one of the original board certified people, and it was, I think partly because of my publications that I was able to be selected. Now you were also involved, while you were veterinarian, in building the endangered species research center in the hospital.

When did that happen, how did it come about?

How did you get involved?

Were there issues, problems, getting it all finalized?

(chuckling) It’s interesting, ’cause you know, as a side, I guess I have always been interested in construction and architecture and design. And so that’s sort of, I don’t know, one of my hobbies I guess, and I love construction. I love physically doing it myself. And when it came about that we were building a new hospital at the zoo, the architects that were hired came up with a preliminary design, and when I looked at it, it was terrible. It just didn’t have what, you know, things were not juxtapositioned correctly against each other. And so that night I took the whole thing that they’d put together and started cutting it up and putting it together the way it should be. And I was very scared after doing that, to fit into the site that it had, that they were gonna really be upset. Because here’s a guy who, you know, doesn’t have any background in architecture or design, and he’s trying to, so.

But when I presented it to them, they said, “Oh, that’s what you want? Oh, we can do that.” And so I really started with the hospital at the zoo, helping out with the design and the construction and the, on the staff at the zoo we had somebody who was in charge of outside contractors, and dealt with the architects and all that. And Charlie was the director at the time, and he talked to Charlie, he says, “You know, Bill knows more than the architects about some of this stuff, you know?” ‘Cause they couldn’t come up with an answer. I’m, “Well, why don’t you just do it this way?” And so they would follow it. And so I got much more involved with the rest of the zoo then, after that was built of the design. And you know, the River’s Edge, Penguin Puffin Coast and so forth, I was intimately involved in all those, and just enjoyed doing it. It was something that I had a certain skill in doing, and so took on that opportunity. You mentioned, we were talking about the hospital that you helped put together.

When you first started, there wasn’t a hospital there, was there?

No, we had a building there, that was not much of a hospital, but yeah, we had a building that, you know, we had some cages, and we had a room that we did all of the necropsies in. You know, we had labs there, so there was a facility there. And later on I did also, when Disney was building their new Animal Kingdom down there, I was consulted on on the design of their hospital down there, how it should be built. So that was kinda interesting too. Now you are the senior veterinarian, but then something happens where you move out of the senior veterinarian position into a new position, from being senior veterinarian and research.

You become the Director of Zoological Operations in 1993?

Somewhere around then, okay. Now you’re moving from veterinary medicine to more of an administration position.

How did that happen, why did it happen?

Were you aiming for this, or what was going on?

Well you know, when you work for any organization, you have your role and I was in my role, but you know how the rest of the zoo is operating too. And so you get involved in the other parts when when you have an opportunity, if you have something to add. And at that point, Charlie was the director at the time, and was, I think, there were a number of people that reported to Charlie, and he needed to streamline his flow chart I guess, of people who reported to him, and wanted others to take over various responsibilities. And so Director of Zoo Operations meant the animal division primarily, education also. But it was taking over not only overseeing veterinary care and research, but also the whole curatorial staff and keeper staff, and education department. So it was, I’d taken on more responsibilities, but it was something that I kind of, you know, had a knack in, I guess. And you said this was through the director then who wanted you to do this, Charlie Hoessle. Now did, you had mentioned before, the last director that we talked about was Bridges.

Did Charlie come after him?

No, Bill Hoff was the first, I mean, Marlin Perkins way back when I was a student, then Bill Hoff, then Bob Briggs was there for several years. After Bob was Dick Schultz. Dick Schultz was a finance person. And it’s interesting, because Bob Briggs was, you know PR, and brought some really good PR, I mean, to the zoo. I mean, Marlin Perkins was a super PR person with “Wild Kingdom” and everything. So each person brought something different. Dick Schultz was finance, and really got things together there. Charlie Hoessle, of course was an animal person.

And so Charlie was there about 20 of the years that I worked under Charlie as director. And each person brought something different to the table.

Did you ever, of all of these various directors that you’re talking about during your career, did you ever run afoul of any of them?

(laughing) I don’t know that I ever ran afoul of any of them, but I remember, oh early on, and Bill Hoff was the director and it was, oh, had to be in the first year that I was there. I mean, maybe even the first month or so. And we were gonna be vaccinating some animals in the children’s zoo, and I don’t remember, some kind of mustelid was there that, and Bill Hoff said, “Well, you need to vaccinate it with, da da da da, such and such.” And that kinda bothered me, and I thought, “You know, I’m the veterinarian, I’m the guy, you know?” You know, you don’t take your dog to the veterinarian, and then say, “Well you know, which particular vaccine are you gonna give for distemper?” You know, and so I got to think about it. “Well, I don’t wanna, how am I gonna approach this?” And so what I did was I asked his secretary, “When’s he gonna be gone to lunch?” And so he was gone and you know, there’s all kinds of different vaccines for dogs and cats that can be used on zoo animals. And there’s a lot of different companies that make them. There’s killed vaccines, there’s modified live vaccines, and so forth for the various things. And so I went to his desk and I opened up all these catalogs, I probably had 10 different catalogs opened up to the various pages where the vaccines were there. And I had them all sitting on his desk during the lunchtime.

And when he came back from lunch, I came in, you know I said, “Okay, here’s the vaccine. What do you want me to use to vaccinate these mustelids?” And he started looking at them and he looked at one, you know, and he started reading the other one, and looked at all of them.

And you know he said, “Use what you think is the right thing.” You know, he never again ever made any comments of what drug I oughta use, or what dose oughta use, or what medication, you know?

He realized that he was going beyond what he should. Now, Bill had a lot of experience in zoos before, and he probably had some experience with other veterinarians that didn’t work out so good. But that was the only time that ever, you know, I will say all of the directors that I worked for, never, you know, made suggestions or told me how to practice veterinary medicine.

Now, when you received this promotion, to more things under your portfolio, were people jealous of you?

Or were they “Oh, now he’s above us and he’s our boss,” and- I don’t know that they were jealous of me. You know, I- Or upset You got the position or- I don’t know if anybody was upset. I mean, I always tried to work with everybody that, you know, it didn’t make any difference what level they were at, you know, in the organization or zoo, I treated everybody well. You were, now it’s taking you away from your daily medical responsibilities.

Was it hard to leave this, the position of being veterinarian, senior veterinarian, doing the research or coordinating all that?

‘Cause now you had a lot more. I will say this, that, you know, I always enjoyed the clinical work. One of the neat things, that I was very fortunate to be at the same institution for 37 years, the same organization for 37 years, but I got to do a lot of different things. And with my personality, that probably worked well, because after I do something for a while, you kind of get really accomplished in it. And not that you get bored, but you wanna move on to something else, something more challenging. And while clinical medicine was really challenging, you know, I was able to then get into a little bit of teaching, a little bit of research and publishing. And then I got into more managing people and administration, got into design and construction and architecture. And then eventually into, you know, manage the construction budgets and financing.

And so I was able to do a lot of different things, and stay at the same place. So that was a really great opportunity for me. Now you weren’t Director of Zoological Operations for a very, very long time because unless it morphs in, you then became the Assistant Director. In 1996, you become assistant director of the zoo.

How did you get this new job?

How did it come to pass, and why did you get the job?

It seems like, you know, as time was going by, I was doing more and more and getting more involved in different activities, of some of which I just took on, and eventually later got the title that matched what I was doing already. But I mean, at the time you become assistant director, the director is- Charlie Hoessle.

Does he come to you?

It doesn’t sound like you’re asking for these positions, but does somebody come to you and say, “How would you like to take on this position?” I mean- I think I was already doing a lot of the activities.

And Charlie once told me the reason that he, I guess promoted me and relied on me was, you know, he had certain things that he needed to accomplish and he would give the tasks to various staff members and I always came through with it, you know?

I always did it and I did it in the time, you know, that he needed it. Where others, I guess failed him at times, and you know, so it was, you know, he knew that if he gave me something to do, it was gonna get done. Talk about your new responsibilities, if you had any. Well you know, I guess finance and HR came into that, where I was overseeing both of those, which I had not overseen before, even though I was, you know one of the things with the outside contractors, and so forth, especially, we were doing a lot of new construction. River’s Edge, Penguin Puffin Coast, some of those things were, just the whole zoo was being redone. And one of the things that I did was, you know, keep us within budget on those. They can easily have a lot of overruns, a lot of change orders. And one of the biggest things, you know, with dealing with outside construction was taking those plans to all of the people involved, all of the keepers involved and what, “Is this gonna work?” And sometimes explaining to them what they have, and what, you know, because not everybody can read the blueprints and you know, “Well I want you, you know, ’cause this is the way it’s gonna be built.

We don’t want you to be in the construction phases and now change this, because it’s too expensive to change then. It’s a lot easier with an eraser and pen to change those things than once it’s constructed, and let’s make sure it’s gonna be built what you need.” And so I was pretty insistent upon that, and you know we, I guess I got involved with more of the construction and the finance part of it, and the HR part of it. And it was again, it was new things for me.

Did you have to leave, or continue to leave the zoo medicine behind or not?

(sighing) I guess I did leave a lot of it behind. I had some good people there. Eric Miller was still there, stayed the rest of his career, and we had another full-time veterinarian, Randy Yungy, who was there at the time. And so we had some good other clinical people that I could rely on and know that the job was, that part of it was well taken care of.

As a quick aside, when you were veterinarian, did you ever work or have a regular physician’s group that came and helped you with unusual or new things?

And if you did, did you develop it, it was already there, or?

I developed it. I called it our consultants group, and I used it as part of our residency program because, we probably had 40 to 50 consultants in that group. And one of the things that I required the residents to do was to make regular presentations to this group. And this group was made up of physicians, dentists, zoologists, veterinarians, people from the university, people from the either Washington University, Purina, there were nutritionists on it. And they would come and the resident would have to present two or three cases, you know, at it. And it was always interesting, because these were people who had their own skills and backgrounds, and they were willing to help us. I mean you know, when we had a, you know an animal that needed some dentistry work, I mean, the dentists loved to come in and take impressions, you know, to make a crown for a mountain lion or something like that. When we had a cheetah that had cataracts, we had three different ophthalmologists who were there.

You know, two human ophthalmologists and one veterinary ophthalmologist, and all wanted to work on the cheetah, and so they were happy to donate their time.

And I had one intern as to, “You know Bill, are you guys upset with me?

You haven’t called me for over a year to come and treat any of the animals,” you know?

And so we had this consultant group that was very helpful to us. And we, like I said, we had regular meetings. I know we had one, it was primarily on nutrition, and I would lead part of it too. And we had Mark Morris there, who’s developed all kinds of animal diets. We had several people from Ralston Purina there.

We had you know, and I says, “Okay, how should we put a diet together?

I mean, what should we do?

What kind of diet should we have for a pangolin?” And I chose a species that nobody would be familiar with, you know?

“Oh it’s easy, you know?” The dentist said, “You know, well let’s look at his teeth and see what kind of teeth he has, and we’ll be able to figure it out,” you know?

And you know, the nutritionist, “Well, it has to be so much balance between proteins and fats and you know, what mineral content and so on.” And the behaviorist said, “Well, you go to the wild and you collect the feces from them, and you know, you sacrifice a few of them and see what they’ve been eating, and that’s how you would figure out their diet.” Veterinarian’s kinda going, “Well, what’s he doing?

Is he losing weight, is he getting,” you know?

And so everybody is finally, it’s coming to everybody’s sight, “Well, we all have an input in this. There’s all, everybody has something to add to it, and you know, and we can come up with something.” And so the consultants group was a really neat group of people that, a lot of them even also became donors to the zoo too, because it was something that they could come to the zoo and and participate, and we used them. One of them was a TB specialist, and I don’t know if you wanna ask about that later, but when we had a problem with TB and elephants, we brought him in.

Now did you feel then that as the assistant director, you were having a major input in starting to shape the direction of the zoo?

Or were you just kinda following what the director wanted to do?

Well, it’s fun. Charlie was a great guy to work for. He was a taskmaster, you better do what he asked. But he really was, really great. Now, I remember one incidence where we were going to do something, we were gonna add to the zoo. Now the zoo is in Forest Park. We have our 93 acres and that’s it. I mean, there’s no chance for expansion into other parts of the park.

But there was this other area that wasn’t being utilized. And our our chairman of the board, very powerful individual in St. Louis, Bob Hyland, he ran the city in a way, because he ran KMOX, powerful radio station. Everybody that advertised anything happened through him, and he was the chairman of the commission. And he had gotten in, and then Ralston Purina was gonna donate, and we were gonna do this, It was kind of a farm in the zoo, so to speak. I know other zoos have done this, but this was going to be different. It was gonna annex about five acres and there was some, all kinds of political problems with that but, and Purina was gonna pay for it. And they put it all together, just some preliminary stuff. And I kind of responded to Charlie, I wrote this whole long thing, because they were gonna have, I guess what we consider, you know, modern farming.

They were gonna have chickens in layer cages, where the legs would come out and so forth. But they’re all in small cages. They were going to have hogs and that on slatted floors, and so forth. And then they were gonna have an area where they would be taking the manure and transforming it into usable energy, and so on. And so I kinda wrote something just to Charlie. I said, “Charlie, you know this is neat, and this is the way things are going, and I have no problem with any of what it is, you know, as far as,” and I already had owned my farm at that time, and was raising cattle. And I said, “You know, this is great. However, there’s a lot of people that are gonna object to this.

While we don’t have, I think we have a great relationship with the Humane Society and that, there are certain animal rights people that don’t necessarily agree with some of the modern farming.” And I said something like, “And this manure transforming, this is a crock of shit. You know, this just isn’t gonna work.” And you know, and I sent it to Charlie. And Charlie didn’t respond in any kind of, you know, he was upset with me. And you know, “I can’t do this,” you know, and so forth. And it really bugged me, because I’d never had that from Charlie before.

And it was like, “Oh shoot, here I’m doing, I was offering some advice, you know?

Oh, maybe I’ll just keep my mouth shut.” You know, it was like that.

Didn’t realize that Charlie felt the exact same way, but he just couldn’t say that to Bob Hyland, who was pushing this farming thing with Purina Mills, you know, down Charlie’s throat, you know?

And it wasn’t until a week later when they were gonna go, the architect that they’d chosen was from, I’ve forgotten where, someplace in Minnesota or whatever. And we were gonna fly, and so here we took Ralston Purina’s private jet on air, and Charlie says, “Well, I want you to go along too.” You know, ’cause he knew that I was going to tell exactly how I felt, which I don’t normally do, but you know, but that’s how he felt. And so I could do it without, you know, and then he wouldn’t have to do it. And so you know, so I guess I did have some influence, but Charlie and I thought a lot alike. And so it was a good relationship when I was his assistant director.

Now during the time you were assistant director, wasn’t there another proposal made to people about a breeding farm?

Charlie and I and a couple of others on the staff, we had always, were interested in acquiring some other property because we were limited as to what we could do within our own, you know, part of Forest Park. And we went and looked at quite a number of different parcels of property, places that, there was one place that they were willing to lease us their property for a dollar a year, you know, for a long period of time. There was another one that was, we looked at a number of them, and because of my experience in owning my own farm and that, I said, “Charlie you know,” the land at this one was very nice, but I said that, “You know, we’re gonna have, our infrastructure that we’re gonna have to put in there is much more expensive than the land itself.” I said, “We don’t wanna be on leased property forever, you know, and put in all this money. We wanna own the whole thing, if we’re gonna do that.” We eventually did get a 350-acre breeding farm donated to the zoo by Mrs. Layman, and that one is still owned by the zoo. Initially about all we did was get the perimeter fence in, and really explored a lot of, whether we brought that about or not. Now it is being used by Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Wild Kingdom Center for Mexican wolves. And so it’s being used as a breeding facility for Mexican wolves, that will potentially be released back into the wild.

But was the original intent to have aurochs, or other animals from the zoo having an ancillary breeding area?

Yes. But that never came to fruition. We never did put animals out there, just because before you do that, you know, you have to have somebody staying there all the time. You have to have security there all the time. It just, the cost of it kinda, it was always on hold.

Now while you’re assistant director doing these kinda things and involved in these various projects, in the back of your mind, did you think about the position of director?

Yeah, I guess that was always, you know thinking, “Well you know, Charlie’s, you know, 10 to 15 years older than me.