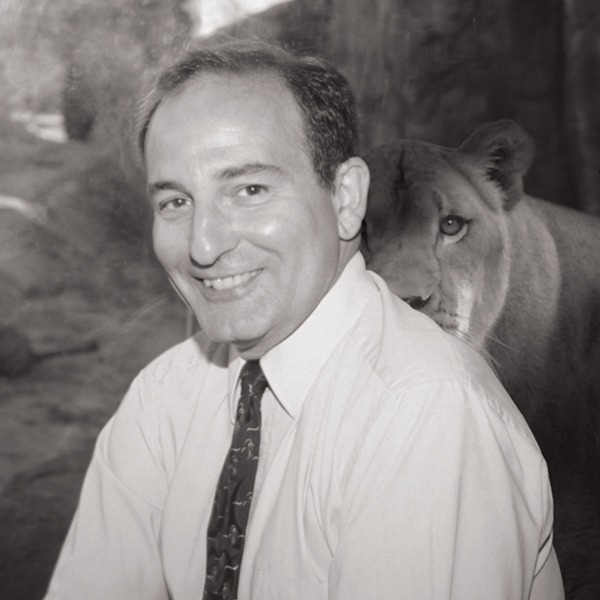

Mark Crandall Reed. I was born in Portland, Oregon on November 28th, 1949, and I was in the zoo profession for about 44 years. And actually I was the executive director of the Sedgwick County Zoological Society was the official title, which operated the zoo for the county.

Now you have a unique kind of history, but when you were growing up, what zoos were you exposed to?

Interestingly enough, my father was the contract veterinarian for what was then called the Portland Zoo. And he actually helped start the zoological society there, the friends group, but he did his work out there in the evening. So I would go out as a four and five year old and had my first elephant experience and seen kangaroos and so forth, but really did not see other zoos until we moved to Washington, DC. I remember stopping at St. Louis and it was later on as you’re growing up, you know, trips up to the Bronx Zoo, to Philadelphia Zoo, Baltimore, and you know, the nearby zoos on the east coast and on vacations, you know, the Florida. Saw Busch Gardens before it was open to the public and you know, the old zoo in Miami at Crandon Park and so forth, but it wasn’t until I actually, you know, was employed as a zookeeper that I started actively on weekends and my days off traveling to all the nearby zoos. I did spend a lot of time at the Kansas City Zoo when I was going to college at Kansas State. Don Deline was the director there. He’d worked for my father.

And so I’d take the train in. It was five bucks to Kansas City and spend the weekend at the zoo. Now back up a little, because you went to Washington, we’ll talk later in detail, but you went to Washington, DC because your father, ‘cos you were exposed to the zoo at a young age.

Your father went to Washington, why?

1955, my father was fascinated by working with exotic animals in vet school. Actually the head of the department was also the zoo director in Manhattan, Kansas at the Sunset Zoo. So he had applied for a job at the San Diego Zoo and didn’t get it. And Charlie Schroeder told him that the National Zoo was looking to hire their first full-time veterinarian and lo and behold, he got it. And we moved there in 1955 and he was the veterinarian. And I literally that first year went in every Saturday morning with him. That was the day he did sort of rounds and necropsies. So the funny story I heard years later was I was fascinated by watching the necropsies, how long the intestines on a sloth were.

And so during the week I’d asked at dinner table, what time today?

Knowing that I get to see it cut up. My dad, I didn’t realize how frustrating it was for him ‘cos here he is trying to save things and I’m getting excited about things dying, but he was basically the full-time vet for about a year and a half when all of a sudden the retirement of the long term director there, Bill Mann, and they offered Walker a temporary position, which he turned down and decided to retire. And my dad was the next in line. They called him down and made him the acting director. And he said, you better give me a piece of paper to prove it ‘cos nobody is gonna believe it. And that night I remember him telling us that he drove by all the entrances and exits to be sure if they were closed or not before he came home. He had no idea what it was all gonna be about, but. So you were exposed to zoos at a very young age.

Would you say that helped your wanting to be in the profession?

You know, actually a combination of, you know, great for show and tell. I had pieces of elephant tusk or teeth and a feather collection and things like this, and growing up in Washington, DC, especially when you got into teenage years, it’s a fabulous town. Everything is free, great museums and art galleries and so forth. And I took a lot of dates to the National Zoo. I knew it well and so forth. And I was actively involved in Boy Scouts, an Eagle Scout, and did the film on loved to camp out. So it was sort of a combination of the outdoor life and taking care of animals. And I originally went to college for pre-vet.

I thought that I wanted to be a veterinarian, probably a zoo veterinarian and quizzed out of some classes, but I got a D in trigonometry and that was the end of my veterinary career before it started. So I switched over to zoology and, you know, didn’t know for sure until I got that first job while I was waiting to go to graduate school. And I knew within days that this is what I wanted to do for sure. Tell me about your formal education. I went to Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas. I graduated in 1972. I knew I was gonna go to graduate school. And at that time, the nearest thing that I could find associated with zoos was at Texas Tech in the Department of Park Administration and Landscape Architecture.

The head of the department knew the zoo world, knew the personalities because of the combined National Park and Recreation Association, the AAZPA within a division, so he knew who all the players were. And it had other zoo people that had gone to the program there, George Bidel Jr. After me, you know, Chris DiSabato had gone and went there. And I was able to do a zoo thesis, which helped me get the job, my first full-time job at the San Antonio Zoo. So let’s start. Now you’re beginning your zoo profession on your own.

And how did you get, what kind of job did you get at the San Antonio Zoo?

That was 1972 I believe to 1973.

What kind of job did you get and how did you get this job?

And some people might think it’s because of who your father knew. And it actually was. It was interesting. I found out a month before I graduated that I was going to graduate. I had forgotten some hours I had earned at a marine biology course I took down in the Mississippi State on the coastline there at Gulfport and I had enough hours to graduate. I thought I was coming back for another semester. And I hitchhiked home real quick. My dad had always said he could help me maybe get my first job.

After that, I was on my own. He got on the phone and he’s talking to some guy named Clayton who I don’t know where or who. And it was real clear early in the conversation that Clayton didn’t have part-time summer jobs. And then he called some guy named Louis and I could tell immediately that I had a position that I could could work at that summer. And they talked for 45 minutes. I’m sitting there wondering where the heck I’m going and got off the phone and found out I was going to San Antonio. It was minimum wage, a $1.80 an hour. I brought home $122 and 22 cents.

I had a garage apartment two blocks from the zoo. I could lay in the Murphy bed and touch three out of the four walls and put my foot in the bathroom and had a Triumph Motorcycle and thought I was king of the world. And I worked in what was called small mammal department, which had giraffes and polar bears and gorillas and chimps and orangs, an interesting title. And I worked there two summers. The next summer I worked in the large mammal department, which was a tremendous hoofstock collection. It had 32 species I think at that time and exposure to rhinos and elephants. And San Antonio is not that huge. It still does have a very large mammal collection.

And looking around, it was just in its stages of professional development under Louis DiSabato. And I went in and had a discussion with him actually my last day on the job. And he told me about this land that had been donated to the zoo to develop possibly a breeding facility or an offsite facility that might be open to the public much in the manner that San Diego Wild Animal Park was. It had just opened. He had been out there for the opening and when I got up to graduate school, I did a lot of research on the land and the issues of ticks and the issues of water were big ones and send ’em a bunch of information on that. And sort of out of that developed a thesis dealing with the development of this land for zoo.

What are the things that have to be considered and how would you go about doing it and what to learn from places that had already done it?

So I did a general problems analysis. I actually had some other graduate students do a vegetation analysis, a soil survey. So used a lot of resources, but in the end, Louis DiSabato ended up being on my board, my thesis board, and basically helped me get a full-time job. At some point, he held the position open ‘cos it had been offered somebody else in the field earlier. And I guess he saw enough in me that they held this. It was actually titled zoologist, I called it. Third line in the totem pole at the time, but they held it open and I started to work there full time in June of ’74 and worked full time for a little over five years before going to the Sedgwick County Zoo, Wichita, Kansas.

So when you worked for Louis DiSabato, who was director, what was your relationship with him?

Did you learn from him, was he a mentor?

Was he a hard task master?

Or because you were the son of the former director. You know, we rarely touched on the son of former director. I had a great relationship with Louis I think. I discovered that over time, I’d stop by near the end of the day and we’d visit for 10 to 15 minutes and you know, he’d relate what his hopes and dreams were and ask how I was doing and how some of the projects I was doing. He really was, it was almost in some ways a teacher, student relationship, a mentoring relationship. And the thing that I got that I’m so appreciative of him is that in some cases, he let me make mistakes. He knew I had to learn myself and others, he would give me guidance on what he thought would happen if I tried this or did that. I had a lot of fun working for Louis.

I had a good working relationship with him. He learned a lot from those gorillas at Columbus, Ohio. I mean, he had those penetrating eye and you could see that quiver in his job when he’d get upset on things. But I can say that I really enjoyed my time. It was a great collection. I mean, it was a huge collection and exposure to animals that some of ’em we’ll never see in zoos again most likely, and San Antonio was just a great town. Now, you said he held quote unquote a job for you and you started in 1974.

Is the title general curator or is the title zoologist?

The original starting title was zoologist. And it was, I mean, during my five years there, I was also put in charge over the horticulture department. I liaison with the maintenance department. I spent a year doing some major overhaul, spent $40,000 on overhauling the aquarium and air handling systems and doubling the salt water. I designed some new hoof stock barns that were built in the back area, it was a little bit of everything. That’s why I called it more appropriately probably the third man on the totem pole. There was an assistant to the director, Ernie Roney. And we ate lunch every day together on the zoo property, you know, normal chain of command there, but I made a point and Louis had an open door and I’d go in there every evening, just about I’d say four out of five nights a week.

And yeah, we’d talk for five, 10, 15 minutes. Louis was one of those guys that got out in the zoo every morning doing a walkthrough and every afternoon for a few minutes somewhere, he knew the zoo. And you could also tell in the afternoon walks, you could tell whether he was enjoying himself or not by those radio calls. One out of whoever and if it was not a good day, you were hoping you weren’t gonna hear your number. My number was 13. Well, now when you started, you really had limited as a zoologist or general curator or that title as third in line, you really only had limited keeper experience.

How did the staff, and I’m sure they knew where you came from, but how did the staff react to this new kid with limited experience being third in line?

It was interesting because of the minimum wage, or in most cases, only five or 10 cents. It was before the zoo became unionized, a tremendous amount of turnover. And one of my jobs was the hiring. And basically I did all the hiring for the keepers, gardeners and maintenance, in addition to my other duties. And you know, the follow through in the probationary system to the point that we were having discussions at two weeks, six weeks, three months, and five months on probationary employees who found that it was easier to take care of issues during that time period, so there was not a tremendous amount of longevity. I can tell you that my second summer in the large mammal department, about 17 people, that I think there was only five there that had been there longer than I had. I mean, it was a hard, tough job. And you know, it was in the days when most of it was spent cleaning the pen and feeding the pen and making sure they had water.

And that’s about all you had time for. The things that we like to think about in Richmond and all the things you can do to talk with the public now and everything, this was before those days that you had that kind of opportunity.

How much freedom did you have in this position?

I had a tremendous amount of freedom. I was amazed how much that Louis allowed me to take on. Basically, I think because I kept him well informed on what was going on, I think he saw the passion in me to always try to make the zoo look better, feel better, better guest services, whatever it was. He was good to me in that aspect. I couldn’t have had a better boss that first five years.

Was the relationship different when you were senior staff than when you were the animal keeper starting out. or?

Oh, totally different. When I was the animal keeper stopping out, you know, I’d see him walk around the zoo and I’d nod, but that first summer, we didn’t talk until that last day really. And the second summer maybe talked a few other times for a few minutes, but he was getting reports. They had a long term superintendent of mammals, Raymond Figueroa, that I’m sure gave him reports on how I was doing. And he was a great task master. You know, he was good at hiding those golf balls in a pin If you didn’t find ’em, you weren’t cleaning the pin right. And I learned about flocks and always double checking and how important that is. And Raymond was also just a good hoof stock person.

He was one of those ones that could see that separation in the hips and know that the baby was gonna be born in the next 24 hours. And you know, all these things that he’d worked there since he was a 14 year old kid. And he was in his early 50s at that time and had done everything at the zoo one time or another, a natural.

As a curator, as the third guy, were there lessons that you learned from your father that you kind of brought with you and used or not?

The lessons that I learned from my father actually probably came in later, but the one lesson I did learn, my dad and I had a relationship early on where I was a keeper. I was sending back cassette tapes with my experiences when I was learning. And I would question some things that were going on at the zoo. And as he explained to me in one of the tapes coming back, and I still have those tapes. I was surprised when I was going through my dad’s stuff that he had some of them. He said, “Until you sit in that seat of ultimate responsibility, there’s no way to fully understand why Louis was making this decision or that decision. And as you move up the ranks, you will start to understand that.” And that was very much a true statement. The other thing that I learned from him was getting out and seeing other zoos.

He constantly traveled. He was also head of the membership of WAZO, so we got a lot of international travel too. At that time, it was IUDGZ, but on weekends, you know, Dallas Fort Worth and you had the Lion Country Safari. There was also a commercial aquarium operation up there. Next weekend we’d be hitchhiking down to Brownsville, going over to Houston the weekend. I can remember sleeping on apartments at Jim Murphy, his house or in the parking lot at Fort Worth. I mean, and he made it up to Oklahoma city one time, but it was starting to see other zoos and how things are going and starting to build that network.

At this time, would you say you’re forming a philosophy about zoo management on your own?

I learned a lot of the technical aspects and the evolving professionalism of the zoo from Louis DiSabato. The philosophy behind it I got when I went to the Sedgwick County Zoo under Ron Blakely.

And that was the basic question of why?

This whole thing about interpreting nature for the layman is the presentation was the overriding philosophy that Ron gave us. But always to be able to answer the question why. If you can’t answer the question why, something’s wrong. In fact, Ron Blakely on the first day in the job told me I would learn just as much what not to do as what to do from him, and he was correct on that. I had a lot of things that I have adopted from him in philosophy. I had some others that I took a 180 degree turn. He was not as communicative with the board and the staff. I decided I was gonna have a total open, transparent thing and his worked for him and my way worked for me when I was able to do that, and I think ultimately it led to my success in many ways.

Let’s talk about this start here. In 1979, I believe you become assistant director of the Sedgwick County Zoo until 1991, but a couple of questions.

What made you decide to seek a job at another zoo?

You know, when I was in San Antonio, I was looking to make that next step. I had figured originally three moves, you know, curator, general curator, assistant director somewhere, become a director. And it felt like I had a broad exposure with this job at San Antonio because of the other branches within the zoo, the maintenance and the horticulture, and had picked up aquarium background. I spent a year soaking everything I could out of David McKelvey when he was hired as the first zoo’s professional agriculturist. And of course, a very famous guy at the time, Joe Laszlo in the herpetological field. And he was a leader in the original environmental chambers and so forth and it was exciting to get him the materials to watch what was going on. So I had a broad, broad exposure and felt like I was ready to take that next step. And I could tell that the assistant to the director there, Ernie Roney wasn’t going anywhere so I started started looking, but the job, I came out of going to the regional conference in 1979, which was in Sedgwick County Zoo.

I’m looking around, the zoo is eight years old. All modern, all new, young staff, they’re excited. I liked what I saw and Louis had sent me up there thinking that I’d see what I’d learned. He was very good about allowing us to travel to conferences. And I got talking to Ron Blakely and vice versa, and I actually even told my grandparents who were both still living in Kansas at the time that I thought I’d get a job offer in six months ‘cos I could tell that the assistant director at the time was probably not gonna be there much longer. And three months later, I got a call one night and I went up to see him a week later and worked out the details, came back and gave a about a three week notice I think and ended up working to that last hour. I always envisioned that last couple days walking around the zoo, saying goodbye to everything and to everybody. I barely made it to my little retirement gig they had done at the restaurant.

And you know, the same thing happened at Sedgwick County Zoo. After X number of years, you start thinking you’re ready to take that next big step and started looking around. I promised both directors, I told Louis when I was hired and I told it to Ron Blakely that I guaranteed him five years.

And I felt like I’d seen too many people in the profession two years here, three years here and jumping around and you know, what did they have to look back that they could say they did or accomplished in that short of a time?

And I felt like at least five years, you could leave something that you could feel and be proud of.

So what kind of zoo did you find?

You said it was a new zoo.

What kind of zoo did you find that you were walking into and what were your new job responsibilities?

Well, the thing that hit me immediately was that this zoo had been master planned from the beginning and that they were following this master plan. They had already done a Farms of the World Complex, a herpetarium, the African Veldt had been done, but not the Asian part. And they had built the first major tropical building in the country. It wasn’t the first, the first was at Topeka Zoo under Gary Clarke. And they were in the process of opening a walkthrough Australian and South American exhibit called the Pampas Outback. And in which you were inside the aviary, which also included exhibits outside this aviary so that you were in the cage looking out into the animals in the open area and a tremendous amount of immersion in this exhibit. There were a lot of first, looking at tortoises with no barriers at the herpetarium. You could actually walk in with lizards and turtles in the Desert Room, the Jungle Walkthrough.

I liked the philosophy. And my immediate responses was the biggest thing I was given when I was there was they had a new general curator, Ken Redman, who later went on to become the assistant director and director of the Honolulu Zoo, was recently promoted up from the ranks there, was to find the animals for this exhibit. And you know, I got challenges of he would like to have some (indistinct), when we were talking about originally was gonna have Australian Dingos. I said yeah, I can get some, and I didn’t know what they were. I went back and looked it up and found out they’re these New Guinea Singing Dogs, and there were none in the country at the time. But I had traveled to Australia already and had developed relationships at Sydney and Melbourne and Adelaide Zoos. And I found some at the Melbourne Zoo and was able to trade three squirrel monkeys for a pair of New Guinea Singing Dogs. And the rest is history on there because from those and another import that we brought in from Germany, they’re now quite, I mean, they’re found in a few zoos, but they’re also in the regular dog world now.

And some people will call them a yellow cur dog and other people will tell you it’s one of the earliest forms of domesticated dog and I don’t get involved in that argument anymore. So you have a new director. I presume he has an absolutely different management style than the former director you worked for.

How easy or difficult was it to adapt to this new environment?

You know, was Ron Blakely was a brilliant man. I mean, no question this guy I’m sure would classify as a genius. And so we liked that. And it was always challenging. As he said, he had a psychology degree too so he’d brown bag psychologists at times and how he worked with people. I took great pleasure in when I caught him in a mistake on dealing with animals, and one of ’em was like the coati. He was calling them coatimundis. And I said that coatimundi means the male coati.

It was one of only two or three that I caught him on something. This guy was well versed in knowing his biology of the collection and animals. But admittedly, he didn’t get out in the zoo hardly at all. At the end, he had a special interest in the domestic animals and spent quite a bit of time down in the domestic concept. And there’s no question because of him, they have a couple of goose and chicken breeds that are still around. He was one of the founding supporters of this within America, what was now the American Conservancy dealing with rare and endangered forms of domesticated livestock. He was on the board there. He was willing to think outside the box on zoo design, which is what I really appreciated.

And that was an area that I feel like that I looked back in my career that it was most fascinating to me, especially with the challenge of the cost benefit ratio.

How much do you spend and what do you get out of it?

Because a lot of things that have been built cost a bloody fortune and you can’t see the animal. I can still remember Louis DiSabato draging me in to look at this picture when they did the great looking exhibits. It was in the old lion house at the Brookfield Zoo here of the four small cat exhibits. And they cost, I forgot what it was, so much a piece or whatever. And Louis said, “If you ever build something like this and spend that kind of money, I’ll come kick your butt,” because you couldn’t see the animals, which is a basic premise. And the challenge of exhibit design is something that, you know, people want to see the eyelashes, the eyeballs, but they want to know they’re in a well cared for large exhibit that meets their welfare needs and have space. So you always have that challenge. And the animal has gotta have a place where it feels safe and so forth, but from some angle still be visible by the public.

So that was one of the things that Ron was really creative and challenged me personally in my designs when I became the director, which led to me constantly trying to learn more. One of the first things I did in my early days at Sedgwick County was take the opportunity and go with Marvin Jones and then Ken Kawata came along and ended up doing 26 zoos in Europe in 21 days. You could do two zoos a day because of the train system. And there were things I saw that just blew me away. And I learned that you could take ideas and adapt ’em for climate, even governance, union versus non-union, utilities. While there’s always new things under the things, but they’re built on little developments that most things that we think are new and exciting have been done in some format before. I mean, the zoo profession goes back thousands of years. There’s been some real creativity that some of us didn’t realize until we see more and more places.

So your philosophy under Ron Blakely you indicated is your own personal philosophy, zoo management and managing the zoo is starting to form. Yeah, I would say that I knew when I was at Sedgwick County that we could do great things, that the biggest challenge would be that I would never have the 40 million dollars or something to build some monstrous exhibit, that we had to build and come up with concepts that would be of world class standards, but not spend the kind of money. And that became in innovation, materials and so forth. And you know, we are not there to display architecture, we’re there to display animals. So you know, people come and come away with an appreciation, that connection with those animals has nothing to do with the architecture or shouldn’t. And I think at Sedgwick County, we very successfully did that on main exhibits. I mean, you can go too cheap and things start falling apart. So there’s a compromise on that when you’re looking at materials, but you know, I never had anybody come to the Sedgwick County Zoo at any time, even dealing with all Blakely stuff, ‘cos he left me a great, great master plan, that didn’t come away surprised and impressed and it exceeded their expectations, which is how I always looked at a zoo.

I went to a zoo, my first visit at any zoo, I had an expectation from something. And if it exceeded that, I looked at it as a great, super day. If it didn’t live up to what my expectations were because I knew the people or something, I was kind of disappointed or whatever. But I feel confident in saying that I never turned around anybody or got feedback that would indicate that nothing less than it exceeded everybody’s expectations when they came. It was a feeling that made you feel proud that your colleagues and your friends were appreciative of what you were able to do, and the community. I mean, we all hear about some of the mega zoos in this country how good they are. And you know, people in Kansas vacation too. They came back and they said man, our zoo is good, if not better than this zoo or that zoo and so forth.

And it always made you feel good. Now 1991, you become the director of the Sedgwick County Zoo.

What happens to allow you to apply for the job of zoo director and why did you want to do it?

Again, I had promised Ron five years and actually it was at six years the first job I applied for came up, Seattle, the one that David Town got, and it was a good experience for interviewing. And I interviewed for many more, pretty competitively came in second or third depending if they listed you or told you why you didn’t get the job. I accepted a job at Auckland and 12 hours later, I had to call ’em back and say that I just couldn’t do it. The long story on that one is probably not worth telling, but I had relatives living in New Zealand and had been to New Zealand quite a bit. It’s a tropical paradise, but I realized that on a professional basis, it would not allow me to grow and would fulfill my need because I wanted this next job to be the job to spend my career at. I didn’t wanna hop around from directorship to directorship or anything. And at the time, I was actually a final three candidate for the job at the Fresno Zoo and I sent them a notice and pulled my name out because of the job at Wichita. Ron retired earlier than we all anticipated.

He chose to do that. And they did an international, not international, they did a national search and hired a head hunter to help. And I am very appreciative. They broke it down to 20 and then narrowed the field down. We went through the essay questionnaires and the phone calls and they broke it down finally to two people and I was one of them. And I was most thankful to Dave Siconi, who was president of the AAZPA at the time. He said, “I don’t even know why you’re looking. You’ve got the best candidate in the country right there,” which was good because that was the one thing that was lacking.

The staff did not have access to the board or we knew the board at all. It was Blakely just basically handled the board himself and minimally at that. He was a very much old style of pretty much kept in the dark. And as a lot of people said, at times he would’ve liked to just shut the gates and just had his little private zoo there to himself to be totally honest with you. So I competed in the final interview and you know, it was one of those interviews, and I’d had some that I had thought I did well, and others I knew that I didn’t. And somewhere halfway through that interview, I can remember feeling I’ve got this. And I told him what I thought my dreams were for the zoo. And I can still remember the one question from the founding person at the zoo, Mary Lynn Priest.

She asked me, “What did I think the attendance was capable of being?” Well at the time, we were under 300,000. Not much, the population of the actual city itself. The metropolitan area was a little bit bigger. And I said, “This zoo ought to be drawing 650,000 people in X number of years” and so forth. I don’t know if anybody believed me, but my last year as director, we hit 711,000 people. And that came with the new elephant exhibit and everything. But we had inched up every year and I had shown him what my dreams were as far as organization of the zoo and told ’em I supported the master plan, but we were able to re tweak it twice. It’s a living document and always needs to be looked at.

And in fact, the last thing I did my last year preparing for leaving and building that last budget was to build into the following budget after I left money for a total professional, strategic planning process and a master planning update review process. So I left my successor the money in that budget, which is what they’ve been going through a year long strategic plan. And I’m looking forward to, and I’ve been in touch with what’s coming out of it. Some of it is really exciting, but I’ll get a review of that here in the next month of what’s come out of that whole process. But I felt it was important the time a new director come in to take a good, hard look at everything. And for the board, it’s important for the board and the community.

You had indicated that your father had said to you, “Hey, until you sit in the seat, don’t keep judging ‘cos it’s gonna be different.” So how different was the role as a director from that of assistant director?

You know, I tell this story. The last three weeks, I can remember that Ron wasn’t there much the last three weeks, burning up some time and everything. And I was telling somebody, I said you know, if that elephant falls in the moat, Ron will get blamed for it because it fell in the moat. The director is ultimately responsible. And sure enough, my first week as the actual director, even though I felt like I had running the zoo for almost those first three weeks before I was actually titled, a new county manager is hired. And this was a public private partnership and they’re a partner and it’s a position on the board. And I had already met him when he had come out to start the job. The day before he came out and bought a membership he toured around the zoo and he told me at the very end of the tour that he would do everything he could to help me.

He believed in museums and zoos and cultural things for the community. And he lived up to that and he’s coming out to the zoo and right as he got to my office and we’re getting in the golf cart to ride down, ‘cos the office is outside the actual perimeter fenced area of the zoo property. And I got a radio call that the elephant is in a moat. And I’m sitting there thinking, oh crud. And he’s all excited. And then he looked at me and said, “This isn’t good, is it?” I said, “No.” So we went down and watched the staff very professionally get the elephant out of the moat. And there was no problems, but my example became my instant nightmare there for a little bit. But you know, as director, I realized very quickly that you’re responsible for every animal in that zoo, every employee’s safety and every visitor that comes to the zoo.

And in fact, you’re responsible to the community because it’s their zoo. And I always said that you knew you were doing a good job when you could go home and sleep at night. When you couldn’t sleep at night, something was wrong.

What surprised you from the shift in roles?

I don’t know if there were any surprises I found out. I think the most important thing was learning very quickly what my strengths and weaknesses were at that level. We all have ’em and I did not understand the budgeting process, the financial process very well. And I knew that at least because I told the finance person we had that we had a budget that was constructed with none of our input. That last time Ron, that last six months, basically we were just all cut out of everything and he’s doing his into the retirement routine. And I said, I’m gonna be spending a lot of money just getting things painted and cleaned up. The zoo was looking a little rough around the edges and I should have gotten that word in July that we were at that edge of the envelope because I didn’t understand the whole reporting things very well, and instead of the third week in September. And you know, we only had an operating reserve of I don’t know, $230,000.

And there was only 30,000 of that left at the end of that first year. And if it hadn’t have been my first year and if it hadn’t had been with the board’s trust in the finance person, I think I could have lost my job easily. I made a point after that that I sat there and she resigned and I had to do a whole budget and I can remember doing it on a legal sheet at home. And I knew I started with $36,000 in the operating reserve. And I left the operating reserve with about three and a half million dollars in it and five million in the endowment that I’d started out with about 80,000. And we had a surplus of almost not quite a million dollars in the black from what was over budget that last year. So we built that operating reserve up to the point that it was a requirement that it’d be 25% of whatever the expenses were the previous year from the zoological society as part of the budget, which was about 50% of the total budget. And it was a good feeling.

I only had to dip into the operating reserve once, which was sort of the prelude to the elephant story when it comes. But I felt very proud of the fact we put the zoo in a good financial setting. And I made a point to know where everything was going financially. I think more of my colleagues had gotten in trouble not understanding that and I came awful damn close. I was very lucky. So you’re the new director. You know the zoo.

And what did you want to be the first accomplishment that you did?

Well, I inherited. They were almost finished fundraising for the North American Prairie Exhibit. He had said that this exhibit could be built for a million, $100,000. We had been cut out of the planning process that last six months during the retiring thing. And I let some people go that first day in the job that I knew weren’t gonna work out and I reorganized some things. And I think in that first week, I called the architect up and I said you need to come out and make a presentation to the staff. I had the veterinarian and I had the maintenance person there and the one curator and we sat down and had a review of this thing. And we ended up making some changes and there’s some really good things there, incredible things actually that he came up with.

But I knew in my heart that this was gonna cost twice what he had told the board, it was gonna cost. So my first problem was convincing the board of that and how we were gonna handle it.

And were they gonna step up and raise more money?

And what could I do to scale back?

And so thank goodness when we opened the bids, the first one was 1.9, then 1.7, then 1.5, 1.3. And we had 1.1 and I had an ace in the hole and I knew I could overhaul the grizzly bear complex and save a couple hundred thousand if I wanted to. But I ended up trading off nails for screws in the boardwalk that was 800 feet long that I later regretted because every single one of those nails comes up were screws down, but we got it built and it was a huge success and the public really loved it. We were all kind of surprised because here we’re talking native animals, but you know, a combination of being proud of their heritage, but the grizzly bears and the bison and the pronghorn were all big hits. And we were able to later add otters and cougars and so forth. But after that, I had some goals. My two big goals were get the chimps and orangutans outside yards. They had a great indoor facility.

Even Jane Goodall came and said it’s one of the best Chimp exhibits in the country. You need outside yards. And we used that clip quite a bit in raising money for that project. And the other desire was elephants and decent hospital facilities. The elephants took a long time. The hospital facilities was right after the getting the chimps and the orangutans out. And we built that in conjunction with the lion exhibit and at the same time, but different funding. You’re running a whole zoo.

How important are amenities at a zoo, and do you think people think of them enough?

If you’re referring to amenities of everything from park benches to decent bathrooms to good food and the gift shop, it’s the entire package. You know, I can still remember Wendy Fisher, the wife of Lester Fisher from Lincoln Park Zoo, giving a talk on toilet paper and how important it was that that bathroom at the exit always be the cleanest because it could be the last impression. If it’s not and it’s out of toilet paper, that’s the one thing they’re gonna remember from the visit. And I had to look at all those, not only the bathrooms, first thing was getting them all air conditioned. Nobody likes sitting down on a sticky seat in the summertime when it’s hot and humid, so that was a priority. And getting indoor restaurant seating, upgrading the restaurant facilities ‘cos we ran them ourselves. We never went out on a contract and I did that for several reasons. I had people on the board that owned major restaurant chains, big time restaurant chains.

And you know, we had a special committee on it. And as long as we could have per caps and generate net profit that met industry standards, it made sense. I mean, it took a lot of work, but you had total control over the thing. And if you had the money for capital investment, it just made sense. And I have a lot of personal colleagues and friends that contract those out. It makes their life a lot simpler, but they lose some control. I mean, one of them even had one of those employees sue him because when the gorilla got out running around, it bit one of these concession people and they turned around and sued the zoo. That’s not good, but I felt like I needed to maximize everything I could.

And if you hired the right people, you could compete at industry standards for food and gift concessions. And so those were important and you know, our job, you had to look at it in some ways in a funny way, our job was to extract every penny and every dime and every dollar out of everybody’s purse when they came to the zoo that day. I mean, the simple thing of just putting in, you know, getting a contract with Coca-Cola or Pepsi and that bidding and how we did that. I mean, we didn’t even have machines in the zoo, so it became very important. People expect a good quality hamburger or hot dog when they come to the zoo. They don’t expect it to be the absolute world’s best, but they don’t think it should be junk either. They know that food’s secondary and qthere’s additional things in that because once you have those, they’re open and people want ’em to be open when they come to ’em, but it’s not profitable to have ’em open those first few hours in most places so you gotta work out compromises. And we always made sure we were open to the max because we didn’t want to upset people.

So yeah, they were quite important. I mean, it’s the whole package of we’re there to display the animals, but it has to be in pleasant surroundings. You talked about amenities at the zoo and so forth.

How important is education at a zoo and can you talk about your college degree program and how that came about?

Okay. First, as far as education, my dad and I actually used to talk about this quite a bit. It’s the one department that you could spend unlimited amounts of money and justify it with the programs and the messages you want to get across. I mean, how much do you do. And it’s also proven you can actually pay if you want to do the payment that you can actually recoup your cost to a pretty good degree if you’re charging for your classes or how much you’re charging. But yeah, and we were in the middle of that. We were charging little amounts, but offered a lot of it free. The aspect of the learning experience coming to the zoo, the best classroom was out there in front of the animals.

Some of the best messages are delivered by well trained docents or even keepers with the elephants there versus in the education building. At Sedgwick County Zoo, we actually had I think the second education building dedicated totally to education was built in 1980. And I expanded it and more than doubled its size. And we were always constantly struggling with that issue, we brought animals a lot heavier into the inside educational aspect and built special facilities for the animals there as a separate standalone collection. And that was a philosophical change from Blakely. We had no animals in for outreach.

And then how far do you go?

You always have those questions in your community and so forth. And then we had a thing on a tremendous number of school systems that couldn’t afford the trip to the zoo. And it’s not because of the cost of coming to the zoo. It’s the cost of the bus service. The days of all the parents bringing their kids, those days are gone, liability issues. They all gotta come in the school bus and so forth. And so we actually developed a special fund for allowing charter one schools to apply for the money to pay for the buses, to pay for the discount on the admissions and so forth. But the one requirement, and we’d give out all the money every year on a first come first serve basis until it was all gone and tried to build it up bigger so they were meeting everybody that did apply.

But the one requirement was that they would have to take at least one kind of structured program while they were at the zoo so they’re just not out running around the zoo the whole time. Now, whether it was in the classroom or out in the zoo on a special tour on someplace that it was done. And we had a reputation. I mean, the second person hired at the Sedgwick County Zoo was the curator of education. At that time, Barbara Burgan, who did many great things in the early days of zoo education, she was on the forefront. The original thing for the zoo science program was a dream of Ron Blakely’s. And originally it was wanted to be with Wichita State University, which is a state school region and has a biology program that’s geared towards people that gotta get the basic stuff for going to applying to medical school and stuff like this. It does not have a great programs that you had at KU or K State or Fort Hayes.

There’s a lot of good wildlife and biology programs at the other state schools. Wichita State really didn’t have it. But we were able to develop a relationship with Friends University, which was originally a Quaker school. It’s got some connection still, but when I became director, we had a problem of the guy that was running the program there, our problems at the zoo, it was a mess. I came within a hair’s breath, a hair’s breath of shutting it down. It was one of the hardest decisions I had to make that I knew knew because it was a mess. I was embarrassed. It was not living up to what we thought it should be or could be.

But at the time, they brought in a new professor to head out the program. I was the new director. We got together and we said we’re gonna make this work. And I am so proud now. It’s a maximum of 60 students in the program at any one time. I was giving away an $80,000 scholarship in my name that had been put into the program. And you know, $4,000 for seniors and three for juniors and two for sophomores where they had to have a certain grade point average and so forth. They do practicums at the zoo.

It was amazing the number of hours that they have, it’s more than volunteering. I mean, they’re working one on one with a keeper, and that’s one of the reasons for how many people you can take ‘cos it does take time to do this. In fact, we have a special fund that allows those people that work with the students to apply for going to conferences, seminars, symposiums, that’s only eligible for those people that work with these students. And we have about eight of the classes that are taught. We teach everything from zoo design. There’s mammalogy, principles in mammal captive care, in care of humans as we call now. There’s a great bird and amphibian class. A veterinarian, there’s a basic zoo orientation class that’s done by the education department.

Horticulture, there’s a horticulture one, zoo horticulture. I would’ve killed for something like this when I was a student. And out of this, there are curators around the country. Bert Castro did it as a master’s special thing and a master’s thing in the early days and now director of the Phoenix Zoo, doing great things down there. It was something by the time that I left, I was very proud of. During the two semesters, once a month, we would have a luncheon in the president’s dining room at the university and all the staff members, the curators and so forth, they were teaching the classes, would come. I would come. Everybody was invited, all the students that were enrolled in it would have lunch and hear the stories what’s going on at the zoo and ask questions.

And I enjoyed it. It sort of kept me young in a way. I remembered those days when I was young and enthusiastic and how exciting things can be when you’re first starting out on your career or dreams. And you could see it in some of these young adults. And I could also see a shift. It was interesting, it’s one of the first places I noticed. I’m looking at the class composition very heavily weighed in women students. And it’s been one of those changes in the profession that I started in 44 years ago with major departments all men and now it’s predominantly female keepers.

The same thing in horticulture, graphics, exhibits, and curatorial staff and probably at the director level. They’re probably at 30% now, which is good. Women are smart. Well, you were talking about these different people that are part of your staff and stuff.

Can you describe your management style and how do you think your staff would describe your management style?

You know, I always said that I asked three things from my staff. They be professional, and that covers a lot of things. That they have fun. And I added a third one and I got this out of Disney, and that is pay attention to detail. Disney uses the word, it was fanatical attention to detail I think he did in his book that wrote… And I basically knew that I had to give them the resources. The compass pointed north with the mission. We had the set of values and tried to stay out of their way when they had what I called the marching orders I guess you’d say, you know, set up this program.

I had pretty open discussions. And when I saw certain strengths in certain areas, I would see if I could compliment that with some extra attention. I believed in staff training and exposure, whether it be travel just to see the zoos, travel with the chances to move animals from zoo to zoo, the symposiums, the meetings. I tried to maximize the number of people going to conferences because it’s continuing education. I think it’s one of the most important things. If you don’t get out and see what other people are doing, because yes true, we have social media now, which so much is out on it. But you know, I took every single newsletter that came and I had a routing slip and I routed it through the zoo. Now so many of tgem are electronic and it’s not as easy to remember to get online ‘cos you’d spend all your time.

I looked through every annual report, everything that ever came. If anything was longer than one page or something like this, it usually went in my briefcase and I read it at home at night. You could learn what to read and what not to read, but that’s how I kept up with a lot of zoos, what was going on. And it’s amazing what some people put in their reports, that you pick up little gleaning things that are helpful. So what my staff would say about me, I definitely had strong opinions on exhibit design and that I shouldn’t see hoses and I shouldn’t see wheelbarrows. We’re not there to display those. And I felt like I had a real fast critical eye from walking around. At the end, I can tell you in that last three years, I didn’t spend as much time out that I would’ve liked to.

Part of it was just this elephant thing was time consuming and overwhelming ‘cos it was a double thing. It was the issue of importing the elephants and the issue of getting this elephant exhibit built in time to receive the elephants. I mean, it was a race against time on many fronts. And I think most people would’ve said good things about me at work. It seemed like most of ’em came to the retirement party. Of course we had free booze. Now you mentioned something where you had talked about, you learned a couple of lessons, I’m kind of jumping around just for a moment, about know where you can find stuff and know what to read, you mentioned.

Can you expand upon that?

You know, there’s a tremendous amount out there. I mean, I had a large book collection one time maybe approaching a thousand books. I mean, it’s big, but it’s not monstrous like Michael or anything. And well, my wife could say that she’d read ’em all. I couldn’t say that, but I could open up and find certain chapters or whatever. I’d tell people about Dennis Merritt’s original thing on keeping armadillos and so forth in volume 16. And I even knew the page number at one time about vitamin K and how important that was for a three banded armadillo. But yeah, you had to remember when you read this stuff or came across it to pass that information on at times.

I think the biggest thing for me was passing on what I saw and learned at other zoos. I was pretty good about giving a slideshow and then eventually a PowerPoint on these travels that I did that I would show. We called ’em Lunch and Learns and all the staff did ’em. I just provided pizza and drinks and it was amazing. People come for free food, but I always made a point of showing the European trips or where I’d been and anybody that went to a conference was encouraged to make that presentation on whether it was going to the waterfowl place.

Mickey, what was it?

Lubbock’s Place, or you know, it was just something to expose the staff to what other departments were doing or in my case, exposing what other zoos were doing. You mentioned rounds.

How important is it for a director, for general curators or whomever, how important, especially director, is it to make rounds?

I think it’s huge. I saw the extreme in action. I was at the Berlin Zoo in 1985 and they had done at that time, this round every morning for damn near a hundred years. They met in front of the lion exhibit. There was the director, the assistant director, the senior veterinarian and all the senior curators. And in less than two hours, they walked the entire zoo. They got a full report at every major stop, at the swine house, the giraffe house, you know, and they could check on whether this got painted or fixed from the day before. They did everything but the aquatic aquarium reptile building there in less than two hours.

And it was impressive, the detail. And I’d heard Charlie Schroeder tried to do it in San Diego and Charlie got out on the grounds every day. And I saw Louis get out on the grounds every day. That was probably an impossible situation nowadays, to be able to do at any zoo of medium size or bigger. But my goal was to get out into the zoo at least an hour and a half every day. That was my goal. And I think I kept it up until the last three years. And I would say that if I counted the amount of time spent down in the construction zone as out in the zoo, probably would have met it.

But you know, they want to see you. I learned real quickly that it wasn’t good enough to be out in the zoo grounds after hours walking around. Your employees wanted to see you see them working ‘cos it also gave them a chance occasionally to dialogue with you. I can tell you as the assistant director, I knew everybody’s name. I knew their spouse’s name, I knew the kids. And I tried to do this all the way through. I’d go to the hospital when anybody was in the hospital. It got harder to do that as the director as the years went by and the staff grew and everything.

But I think the most important aspect for me, of anybody, but I know that communication and that’s being able to talk at a level with those that are your board members and donors out in the society and with passion to keep them excited and be able to work the other way too, down through your employees, that the work that we’re doing was important. That you realized to share with them that same passion I was showing at the other direction of why this is exciting and why we need to do this and be able to talk to people. And for some reason, I had that capability and it was one of my major strengths. And I think it was one of the most important ones ‘cos you can’t do it alone. If you can’t get the people working for you excited about it, you’re in trouble and vice versa. I had to pick out my biggest strength, that was passion and communication. And part of it’s going out, I’m a zoo buff. I love seeing the zoo to start with.

But you know, we had a standing thing. You’re not supposed to walk past trash and things like this. You talk about people working with people.

Did you have a docent program and how important was it?

Ours was… The first full-time new staff person I created as director was a volunteer coordinator. And we decided to open volunteerism up to all areas of the zoo. We had volunteers in the maintenance department. We had more volunteers in the horticulture department than any place originally ‘cos everybody knew whether they had a green thumb or not. And whereas they might not know about working around the animals. So with the education with the docents, it took longer. But under Sinead Anderson who came down from a program that had a very good docent program in Sunset Zoo, she has expanded that.

Not only expanded the paid staff, ‘cos she could show me that adding these staff members, we’d generate this much more money to pay for it, but she saw it and knew how to use volunteers and became a greater outreach. You know, there’s no question, the public that come to the zoo would rather hear about the rhinos from the keeper than they would from me ‘cos they wanna hear the stories. They wanna know the names. They wanna know about the personalities and nobody can be expected to know all that except for the person who is working directly with them. And you know, after the keeper, if there’s a trained docent that’s in that area regularly that knows those animals and knows the keepers. You know, whether you call ’em keeper chats or whatever or spontaneous, I mean, I think that’s the greatest thing was to see people that really liked it. They could see somebody was seeing something neat and they’re on their way to break and stop and take that minute or two to say what you’re seeing is really cool. It’s that connection with the people at the zoo.

And like I said, it’s so hard to judge the impact and there’s been all sorts of studies. You know, the one major study, I can still remember dealing with it. We had their attention for 45 minutes. And after that, it was family discussions or the monkeys look like Uncle Joe or something like that. And that’s why I tell people one of the advantages of membership is come to the zoo and see one or two things and come back later instead of trying to– Nothing I hated worse was seeing some kids drag their parents through the whole zoo in that once a year trip or the parents dragging the kids through that once a year trip, the biggest advantage on membership. Now there are some issues with memberships and membership benefits. You gotta get those matched right with the cost of general admissions. And you know, a lot of people discover when they open up the zoo and late nights and things like this, it’s mostly members coming ‘cos they’re the ones that know about it immediately.

But they’ve already eaten dinner and they come more often so they don’t spend as much money so you don’t have as high as per caps. I mean, there’s all these things that have to get tied into that formula. But we had 247 acres. The public is probably seeing 140 of it. It’s not like New York where people walk or Chicago all the time. They don’t think about walking around the Bronx Zoo ‘cos they do it all the time in New York City, which everybody wants to drive up to the store they’re shopping at. And so we had a free transportation system with major drop off, pickup and drop off points. You know, timed it right with the admission price to cover the cost so there’s no charge for getting on or off.

Unfortunately time, a lot of people that are riding those are the people that ought to be walking. But it’s also helped obviously over the years. We have the shade now and we didn’t when I first got there. Oh, it was a hot place to walk around then in the summertime, but. Tell me about some of the exhibits you champion and the highs and lows of each. And I’m just gonna read a list and then, you know, we can kind of do that. You did Zoo Hospital, the Downing Gorilla Forest, the Cessna Penguin Cove, North American Prairie and the Slawson, if I’m pronouncing a family tiger trek.

Can you give me some highs and lows about these things?

Well, some were exciting, neat. The interesting one, the first one right off the bat after North American Prairie, which you talked about a little bit was the Koch Exhibit, which was the outdoor chimp and orangutans. You spell that, right, Koch, K-O-C-H. Koch is the Koch family of political flame now, fame. And you know, it was named Koch orangutan chimpanzee habitat spelled out the name. It’s how we got the gift money and they have continued supporting the zoo. You know, they had their company picnic at the zoo. That’s an automatic almost a hundred thousand dollars because of what’s generated out of that one company and their picnic.

And they also pay for half of every membership for every employee that joins. And you’ve got 4,000 employees, that’s a good chunk, but we delivered that exhibit and it was on time. The Kochs were very proud of it and happy. They felt like it was one of their most successful. Up to that time, they said it was their most successful public display ‘cos it was a very private company. I mean, it traded places back and forth with the largest privately held company in the world. He’s the sixth or fifth richest person in the world. And we’d like to see them doing a lot more eventually, maybe someday, but because of that success and on time, I had the junior league.

They’d already picked out a 75th anniversary gift, but some of them weren’t happy with what they were doing. They wanted to think bigger. And they came to me and I gave them, here’s an elephant exhibit for this much. Here’s a lion exhibit for this much. And they chose the lion exhibit. It was cheaper and they raised the money. This junior league, 1.9 million dollars, At that time, junior leagues were doing 25 to $50,000 for education programs. And I got more calls for more directors when that was announced of what the junior league was doing ‘cos originally it was one and a half.

They just kept adding more. And it’s how I met my great fundraiser through this program ‘cos she was the one doing it in junior league. And this was done with the recommendation on the final vote when we made our presentation of somebody from the national office being there telling ’em not to do this ‘cos it didn’t meet the junior league’s mission. And I was told when I retired that this thing passed by only one or two votes for them to do it. Not because of the project.

They were more nervous about, could they raise that much money?

‘Cos it was the biggest thing they’d ever done. Well, that went open to a huge success. And that’s what led to the Downing Gorilla Forest. I just got a note from my other patron saint at the zoo, Mary Lynn Oliver, who’s from the Beechcraft family, the Beech family, and they wanted to do a major exhibit. So I wrote ’em a nice long thing ‘cos my next major project, I wanted to get these elephants out of the exhibit they were in. And I went over to visit with them and I sat down and I realized in 30 seconds that it was gorillas or nothing because they had just come back from sitting down next to the mountain gorillas 10, 15 feet away. And they had that mystical experience and they wanted the children, and they said that first, the children and the families to have that experience.

Could I do that?

And I looked at them and I said, “With your help I can.” Because I knew that it was in our master plan. And you can’t ever turn down money when it’s offered. I don’t care if it’s 10,000 or whatever. Oh, we can’t do gorillas now, I gotta do that. It changed things rapidly. And we spent a lot of time figuring out how much money. And basically this was, I said I’d been to every single major gorilla exhibit in the country but one because that’s one I had targeted. It was on the master plan and I knew I’d build someday.

And they basically said, what’s the best one in the country?

And I said for us to look at as the best one in the country is Congo. We flew to the Congo. The staff there did a great job and I picked it. For one, it’s a great exhibit, but it also encompassed bongo and okapi and red river hogs and so forth. It was a so geographical display and so forth. It was more than just gorillas.

And they bought into that and the Olivers decided they liked the okapis and said, can we get those?

And I said with your help. And so they made a four million dollar donation. The Olivers made a million dollar donation. Raised the rest fairly quick. I figured about 6.4 million dollars, which goes a long way in Wichita. And you saw a quick script. We learned a lot from the Congo. We’ve got that viewing circle that’s jetted into the exhibit so you have gorillas almost on both sides of you, in front of you and a nice big yard that goes up in a bowl shape.

And you can’t see what’s holding him in there and been successful breeding them and have babies there now. But it was my first design build ‘cos this guy wanted the money quick and he wanted babies. And all I could get was males. And I had a choice of 32 males and you know, we started with eight and I worked very diligently with the gorilla SSP and worked with the plans we built. The first major place that could hold a lot of male gorillas. We held nine males at one time and had a rotation system and they had an off exhibit display. They had an outside display and an inside display and sometimes we’d mix it, twice on a day occasionally. But most of the time it was on a daily basis they’d get moved to different places.

But on the design bill was getting that price down. ‘Cos at one point I shut down construction on it from August for four and a half months how to figure out how to cut some money out of it without affecting what I’d promised and what would be noticed by the public.

And we did it and there’s not one person that’s ever gone through there That’s noticed anything that, why didn’t you build this or why didn’t you do this?

I mean, you just had to be creative. And we already had the walls and the foundations for the building and the outer walls done. So we had the area, but it was something I sweated over a lot and I’d never do another one that way. And I never did, but we got it done and built on time. The donors were happy. And that first big party in there, two new exhibits came out of that first big party. There was a party for the YPO, young person’s, it’s a professional group of young presidents. Well, this was the meeting where they invite all the old former ones or the older ones and the Downings were there.

And this gorilla is up there making faces at Paula Downing and they’re getting all these accolades. And right after that, I had Mr. Slawson come up and said he wanted to do an exhibit at the zoo too. And then I had the Cessna Aircraft company come up and said we want to do an exhibit. Well, I went over to Slawson’s office and I walked in and I’m thinking elephants ‘cos I know this guy can afford it. This guy is in that exclusive club financially. And I walked into that office and I saw these 10, $15,000 tiger paintings everywhere. I thought tiger and I said holy cow, it’s tigers or nothing. His challenge for us was he wanted to do it with matching funds without donors from the board.

He put a million dollar check on the corner of the table for me to look at and said you match this million dollars and I’ll give you another million. Now, normally that’d be fairly easy. This guy had also earned some major enemies in town because he’d gone bankrupt twice in his thing and never paid some people back on things because of the whole bankruptcy laws. Thank goodness his wife was totally loved, but we found new donors through that. And he has since passed on, but he loved the exhibit and because of his reputation, it was one of those ones. I did the gorilla thing on a handshake for four million dollars. This one, the board because of the guy’s reputation and so forth and involvement in things, they wanted this one out in a solid contract and it took forever and contract number seven looked like version number 11, and we finally got it. And he was the least problem with any donor I ever had, ironically, but Cessna originally wanted to do the penguins.

And my instant reaction was penguins is in the master plans. It’s combined with the sea lion and an aquatic complex, aquatic complex. And it took me a while before I felt comfortable realizing that the penguins, if it was done right, could be the first phase of the aquatic complex. And so it was built with that in mind. And the next thing was how brave Cessna was sponsoring an exhibit for a bird that can’t fly, an aircraft company. They had fun with that. They had pictures of penguins all strapped in to the Cessna jet, you know, things like this. And you know, we obviously had the story they fly, they just fly underwater.

And that was a lot of fun. And again, getting creative, we built for 40 penguins and added extra filter systems in for it. And again, I learned Central Park Zoo, that indoor penguin exhibit they have is 50 feet long and felt real comfortable with it. The size, some structure got away from the straight line. Going back to Hediger, there’s no such thing as a straight line in nature. And to break up that thing and went for the depth. And because of malaria and avian influenza and the fact that our mallards and birds carry all sorts of things, it’s netted over top.

And how do you create a seashore looking feeling in the plains of Kansas?

We had some interesting challenges. And it will always be probably one of the most visited exhibits in the zoo because it’s right across from the main restaurant. It’s an easy walk. You know, it’s one of those easy outdoor walkthroughs and people like things that are black and white, whether it’s zebras, pandas, black and white ruffed lemurs. There’s something about black and white, and pandas it helps they have those big black patches on their faces. But we opened it at the same time that “March of the Penguins” and that other cartoon thing was out, so penguins were all the rage and have been since. And we picked Humboldt penguins and been very successful breeding them and sending out smaller groups to other zoos now. And it’s been a great hit.

That was a lot of fun, but that was our first experience in getting into heavy duty filtering systems and it was a whole new component for the zoo. Let me ask you about relationships, two specific.

What was your relationship to animal rights groups and humane society groups over the years?

And then to talk about your relationship with the zoo society and how did it change over the years?

We were fortunate, you know, I say in Kansas we eat meat. There was locally, we have a Kansas Humane Society. As you know, it’s not related to the American Humane Society and we had a working relationship with them on assisting and helping and still do. I made a major donation to them when they built new facilities and I’m proud of that relationship, it’s always been good. They’ve come to us for help at many times. There was no organized animal rights group or PETA in the zoo. We never had any complaints. I had one lady that for years wrote me about the elephants and I would write her back.

And over the years, she’d remind me of what I’d said over the years that I hadn’t fulfilled those promises yet on the elephant exhibit. And when the time came, she actually made a donation, even though she didn’t feel that elephants should be in zoos, but it was funny. We never had the picketing or any of the problems. In fact, neither Dallas or Omaha when we did the elephant thing, had those issues simply ‘cos I think we were all in the Midwest. We all had good zoos, a good branding community, looked at as community zoos. Dallas hadn’t had that earlier, but they had built that with all the new stuff and then when the society took over the zoo there. Omaha was beloved in their community. And you know, we had cheering crowds and people that camped out for five hours in the parking lot waiting for the elephants to be trucked into the zoo and we still had the police escorts and all those stuff.

When this went public, because at the last minute the government knew they were gonna get sued for issuing the permit, that they would have to do an environmental assessment. It had been declared that wasn’t needed because they’d done one earlier and this was the assessment of the elephants coming in this country, the environmental impact, which had nothing to do with us. It’s whether these elephants would multiply so fast or bring in diseases or things like this that hurt the environment. But because of that, it gets published in a federal register and there’s a comment period. That generated probably 20,000 notes, cards, emails, mass mailing, you know, mass things done by the animal rights groups. Three essential death threats for me are ripping me out of my house and burning my house down, things like this. But they were all from the east and west coast. Those got turned over to the FBI.

I mean, we learned all the lessons from San Diego and Tampa, what they went through and what to prepare for. And I made a mental point of realizing what was going on. Every single one was read and looked at by our marketing department. I said I don’t need to see any of these unless you think I need to see any of them. I mean, I know what’s being said or something like that. I’ve got no time for what was going on to push the average to count today. I didn’t feel like I need to know. So I think that’s probably been the most rewarding thing was after that exhibit opened and I’d see people, I’m getting teared up, seeing the elephants that would’ve been called in a beautiful exhibit, and our old female as the matriarch.

It was cool! So that was my reaction on the thing. I think part of it was, you know, you can call it the brand of the zoo, but it was truly seen as the community zoo and the community was proud of what we’d done.

Why are you emotional, because you survived this or because you gave them what you had the vision of?

Oh, I think it was just cool to see these elephants in. One, alive, two, our old female who had always been the matriarch when we just had two, but assume this and the public’s reaction. They were just so moved about wow, the exhibit, the elephants, a chance to, you know, we tried to design it in such a way as to let the elephants be elephants as much as possible. Feeding was up so they got good neck muscles and trunks and they’re not eating off the ground. And you know, these different feeders and keeping them moving, some of the new aspects of the exhibit. And a total no contact at all, except for the touch pole. And yet, you know, able to draw blood. We felt we built at the time, the best elephant exhibit in the country, a place where people can come and if they’re gonna do a new one, here’s one to see, to build upon, to start, to take it to another level.

But we felt like this exhibit took elephant exhibits to another level. It wasn’t the biggest, it was five acres. The biggest elephant pool in the world. We tried some new things, but for me personally, it was the most satisfying thing and the thing I’m most proud of. But the board during this time, I was upfront. I told ’em what to expect. And yeah, we went through periods of secrecy. I mean, this was the one thing where that transparency, we had to keep this, I mean, it just slowly came out.

We actually made it within 24 hours of what our deadline was for how long we wanted to keep it a secret from the shipping date actually over to the out of Africa to the zoos. We kept that much of a clamp on it. Originally, we thought if it hadn’t been for the environmental impact statement, we would’ve been able to bring ’em into the country just like Pittsburgh did without anybody knowing. You have said, we talked about elephants, you have said that this move was the acquisition, was the pinnacle of your zoo career.

Why?

Well, to start with, it’s every kid’s dream. They go to Africa and bring animals back. I mean, that was my dream was the dream of old of going to get the animals for the zoo. I mean, that was right out of Dr. Seuss. You know, if I ran the zoo. The story was that I was a month away in the fall of 2013 of telling our board that because we no longer met standards of which my mammal curator and I as involvement with the AZA, had helped write the standards that had been elevated. The bar had been raised and we didn’t meet it anymore. And even with a five year grace period, we did not look like we were gonna come anywhere near to meeting it.

And I had earlier, when I first took over the zoo as director, had that decision, like do I send them out for breeding or do I hope that artificial insemination can be done?

Well, that took a little bit longer than thought ‘cos I decided to keep and wait for that. And by the time we got it, it was too late. We did try it. But we now know that elephants under 20 years of age, if they haven’t had that first young, it’s not very likely that it’s gonna happen or be successful. So I knew that Omaha and Dallas were in serious discussions about trying to import some African elephants. I got a phone call from Dennis Pate asking if I would consider joining in those discussions. And I told my board president and my major fundraiser that we’d been invited to possibly participate and there was a meeting and asked for their blessing to go down. We met in January of ’14 in Dallas.

We had Ken Stansell, who retired as the acting director of the Fish and Wildlife Service who had been head of the permit office when the elephants were imported 13 years earlier by Dallas, I mean by Tampa and San Diego. And we went over what we thought the options were. And at that time, literally every country that had elephants that any reasonable attempt could have been made, none were available or we couldn’t for various reasons. The only countries that had available elephants were Swaziland and South Africa. And South Africa, we knew the political situations were such that it would be a major effort. Though they were cites of two, which would’ve made it easier permit wise, but we checked some back channels there and so forth or Ken Stansell had checked and so forth. And Swaziland had recently done an aerial survey and took a look and they knew they had a number of elephants that they needed to get down. They were way past their carrying capacity and that they thought they could provide maybe 15 elephants or 12, 15 elephants.