Well, my name is Karen Sausman. I was born in Chicago, Illinois, and on November 26th, 1945.

Well, my name is Karen Sausman. I was born in Chicago, Illinois, and on November 26th, 1945.

What are some of your earliest memories of zoos?

What are some of your earliest memories of zoos?

My very earliest memories is of Lincoln Park Zoo, and of the rookery as we were not a very wealthy family. Indeed, we were quite a poor family, and so the zoo was free and we lived on the Near North Side. So, I think I was predisposed to wind up being in the zoo business because I was at the zoo almost every weekend because it was a free place where my dad could take me.

My very earliest memories is of Lincoln Park Zoo, and of the rookery as we were not a very wealthy family. Indeed, we were quite a poor family, and so the zoo was free and we lived on the Near North Side. So, I think I was predisposed to wind up being in the zoo business because I was at the zoo almost every weekend because it was a free place where my dad could take me.

Did you have a favorite animal at the zoo that impressed you?

Did you have a favorite animal at the zoo that impressed you?

As I got older, oddly enough, I always loved the antelope. I could walk, maybe because they were kinda built like horses and I liked horses, but I used to walk the antelope string a lot, and particularly when I could go to the zoo on my own.

As I got older, oddly enough, I always loved the antelope. I could walk, maybe because they were kinda built like horses and I liked horses, but I used to walk the antelope string a lot, and particularly when I could go to the zoo on my own.

Now, tell us a little about, maybe the family life, what’d your father do for a living?

Now, tell us a little about, maybe the family life, what’d your father do for a living?

I was an only child and my dad worked as a production manager for Curt Teich Postcard Company on Irving Park. And my mom periodically worked out of the home, but most of the time she was home.

I was an only child and my dad worked as a production manager for Curt Teich Postcard Company on Irving Park. And my mom periodically worked out of the home, but most of the time she was home.

Did they influence you in any wave toward animals or was just your exposure at the zoo something that brought you in a certain direction toward nature?

Did they influence you in any wave toward animals or was just your exposure at the zoo something that brought you in a certain direction toward nature?

I think it was mostly the exposure at the zoo was my, my mother certainly was not interested in anything to do with animals, domestic or otherwise. And my dad was too busy working to worry about it, but I always had this love, although I was not allowed, we lived in a one room apartment. And so, there was certainly no room for animals and my mom didn’t ever encourage animals, and then when we moved to a larger home near Des Plaines, again, she had no interest in having any animals in the house of any kind.

I think it was mostly the exposure at the zoo was my, my mother certainly was not interested in anything to do with animals, domestic or otherwise. And my dad was too busy working to worry about it, but I always had this love, although I was not allowed, we lived in a one room apartment. And so, there was certainly no room for animals and my mom didn’t ever encourage animals, and then when we moved to a larger home near Des Plaines, again, she had no interest in having any animals in the house of any kind.

Were you were walking distance to the zoo or were you, did you have to physically get transported?

Were you were walking distance to the zoo or were you, did you have to physically get transported?

I had to have transport ’cause we were at a Lincoln & Montrose. So, it was a ways away. And when you were at the zoo as younger, did you know about Marlin Perkins and… Absolutely.

I had to have transport ’cause we were at a Lincoln & Montrose. So, it was a ways away. And when you were at the zoo as younger, did you know about Marlin Perkins and… Absolutely.

Did you watch him on television?

Did you watch him on television?

Yes, once we could afford a TV. I used to watch him on television, you bet. Absolutely.

Yes, once we could afford a TV. I used to watch him on television, you bet. Absolutely.

So, you knew he was the director of the zoo and- Did you ever bring home animals or you weren’t allowed?

So, you knew he was the director of the zoo and- Did you ever bring home animals or you weren’t allowed?

Weren’t allowed. No, that was forbidden.

Weren’t allowed. No, that was forbidden.

Can you tell me something about your schooling?

Can you tell me something about your schooling?

Well, I went to public schools and then once I finished high school, I knew I needed to get a college degree. Again, there weren’t any funds for such things so I started working, but unlike most young gals, instead of babysitting and doing things like that, I, by that point we were living in Des Plaines area, I started working for a dog kennel. I decided to get my dogs and my animals one way or the other. So, instead of babysitting, I made money working in a dog kennel and saving money to go to college. So, I went to first two years to something that probably doesn’t exist anymore, it was called Chicago Teacher’s College. And because it was essentially as cheap as you could go and get at least the first couple of years of education. And so, I went there. By that time I was driving, had my own car.

And so I drove to that and then after the first two years, I kept saving money and then transferred to Loyola, and I wanted to, planning to be a math major because at that point, although I, by that age, I knew I really wanted to work somehow with animals, I also knew that there wasn’t any career in animals for young ladies. So, I decided I’d be a math major. I was good with numbers. And so I went to Loyola. I wound up at Loyola at the Water Tower. And while I was there, I was still visiting Lincoln Park Zoo on a routine basis, but I was also at that point earning money to go to school, riding, exercising horses, and still working with dogs (chuckles). Tell me about the horses, though.

And so I drove to that and then after the first two years, I kept saving money and then transferred to Loyola, and I wanted to, planning to be a math major because at that point, although I, by that age, I knew I really wanted to work somehow with animals, I also knew that there wasn’t any career in animals for young ladies. So, I decided I’d be a math major. I was good with numbers. And so I went to Loyola. I wound up at Loyola at the Water Tower. And while I was there, I was still visiting Lincoln Park Zoo on a routine basis, but I was also at that point earning money to go to school, riding, exercising horses, and still working with dogs (chuckles). Tell me about the horses, though.

How did you evolve into working with horses?

How did you evolve into working with horses?

That started when I was very young again, in that Chicago Near North Side flat. We were still in a neighborhood where the ice man delivered ice for the ice boxes. And he delivered them in a wagon drawn by a horse. And my dad knew the ice man, and knew where he stabled his horses. And I’ll never forget the gentleman’s name because I, my dad would take me there too ’cause I was happy there and it was free, and the ice man would let me ride around on his horses. And ultimately, both the ice gentlemen named Mr. Rody, moved out towards Des Plaines and we then moved out towards Des Plaines, and then he introduced me, Mr. Rody, to other people who had horses and told them I loved horses and I love to ride, and so he wound up introducing me to Henry Silverman’s trainer and he had Delaney Farms, which was over near sort of the Nile’s Park Ridge area off of Golf Road, not too far. So, I used to exercise his Saddlebreds for money.

That started when I was very young again, in that Chicago Near North Side flat. We were still in a neighborhood where the ice man delivered ice for the ice boxes. And he delivered them in a wagon drawn by a horse. And my dad knew the ice man, and knew where he stabled his horses. And I’ll never forget the gentleman’s name because I, my dad would take me there too ’cause I was happy there and it was free, and the ice man would let me ride around on his horses. And ultimately, both the ice gentlemen named Mr. Rody, moved out towards Des Plaines and we then moved out towards Des Plaines, and then he introduced me, Mr. Rody, to other people who had horses and told them I loved horses and I love to ride, and so he wound up introducing me to Henry Silverman’s trainer and he had Delaney Farms, which was over near sort of the Nile’s Park Ridge area off of Golf Road, not too far. So, I used to exercise his Saddlebreds for money.

But later you were doing some teaching in the Lincoln Park area?

But later you were doing some teaching in the Lincoln Park area?

Yes. Because I was exercising Saddlebreds, when I went to Loyola and entered Loyola, I had to meet with a counselor to look at my current credits, and I also had to convince the powers that be at Loyola that I could only take morning classes ’cause I had to work in the afternoons and evenings. Otherwise I couldn’t be there ’cause I had to put myself through school. And so, I met with this Jesuit priest about my class schedule and he said, “What do you want to do for physical education classes?” And I said, “Well, frankly, I try never to take any ’cause I don’t have the time.” And he said, “Well,” he said, “But what do you enjoy doing?” And I said, “Well, I ride horses.” And he said, “I would love to give horseback riding as a class at Loyola.” He said, “Would you do that?” And I kinda looked at him blankly and I said, “Well, what do you mean would I do that?” And he said, “Well, if we can arrange it, and we can find a stable, could you teach horseback riding and you’ll get your college credit?” And I said, “Well, yeah, I guess so.” So, we went down off of Cannon Street and there was this old stable in this three story building, and so three times a week I would teach horseback riding, which, and when I was waiting often between my last school class down at the Water Tower and out there, I’d just hang out in the lion house and stay warm and get to know the keeper staff. And eventually they said, “Well, if you need a job, you ought to try workin’ around here.” Well, I got a volunteer job. We’re gonna get back to that in a second. that’s how I wound up teaching horseback riding for Loyola. Now, you mentioned the kennel, that you were working in a kennel.

Yes. Because I was exercising Saddlebreds, when I went to Loyola and entered Loyola, I had to meet with a counselor to look at my current credits, and I also had to convince the powers that be at Loyola that I could only take morning classes ’cause I had to work in the afternoons and evenings. Otherwise I couldn’t be there ’cause I had to put myself through school. And so, I met with this Jesuit priest about my class schedule and he said, “What do you want to do for physical education classes?” And I said, “Well, frankly, I try never to take any ’cause I don’t have the time.” And he said, “Well,” he said, “But what do you enjoy doing?” And I said, “Well, I ride horses.” And he said, “I would love to give horseback riding as a class at Loyola.” He said, “Would you do that?” And I kinda looked at him blankly and I said, “Well, what do you mean would I do that?” And he said, “Well, if we can arrange it, and we can find a stable, could you teach horseback riding and you’ll get your college credit?” And I said, “Well, yeah, I guess so.” So, we went down off of Cannon Street and there was this old stable in this three story building, and so three times a week I would teach horseback riding, which, and when I was waiting often between my last school class down at the Water Tower and out there, I’d just hang out in the lion house and stay warm and get to know the keeper staff. And eventually they said, “Well, if you need a job, you ought to try workin’ around here.” Well, I got a volunteer job. We’re gonna get back to that in a second. that’s how I wound up teaching horseback riding for Loyola. Now, you mentioned the kennel, that you were working in a kennel.

Were you learning any life lessons at the kennel while you were working there that stood you in good stead?

Were you learning any life lessons at the kennel while you were working there that stood you in good stead?

I mean… I imagine the first life lesson that I learned, which didn’t seem to be much of a lesson at the time, but I guess it might’ve been, is that these animals are totally dependent on us. And so, doing a good job, making sure they’re properly cared for, noticing whether they’re sick, ’cause these were big breeding kennels, a big Doberman Pincher and Great Dane kennel in one case. And then in my later, last couple of years at the college, an Italian Greyhound and Whippet kennel. Well, I actually lived onsite. And you had to learn to look at those animals and see if they were all right, because they weren’t under feet like our pet dogs. These were kennel dogs and keeping them really clean and keeping, being aware of their temperaments, being aware of whether they looked a little off that day. So, I learned pretty quick.

I mean… I imagine the first life lesson that I learned, which didn’t seem to be much of a lesson at the time, but I guess it might’ve been, is that these animals are totally dependent on us. And so, doing a good job, making sure they’re properly cared for, noticing whether they’re sick, ’cause these were big breeding kennels, a big Doberman Pincher and Great Dane kennel in one case. And then in my later, last couple of years at the college, an Italian Greyhound and Whippet kennel. Well, I actually lived onsite. And you had to learn to look at those animals and see if they were all right, because they weren’t under feet like our pet dogs. These were kennel dogs and keeping them really clean and keeping, being aware of their temperaments, being aware of whether they looked a little off that day. So, I learned pretty quick.

So what kind of jobs did you have at the kennel?

So what kind of jobs did you have at the kennel?

Well, I was just some cleanup, feed ’em, clean ’em, and then eventually show them, go to the dog shows with them on the weekends, and either just assist or if they needed me to go in and handle the dog and show the dogs for ’em.

Did that carry showing the dogs carry over and as you continued your life?

Yes.

Yeah, I stayed enjoying dog shows and still just finished showing my last groups of dogs a few years ago and said, “Okay, I think now I don’t need to do this anymore, but yeah.” you mentioned that you would hang out at the lion house at Lincoln Park Zoo and the staff is saying, “Hey, why don’t you get a job here?” How did you get a job at Lincoln Park Zoo?

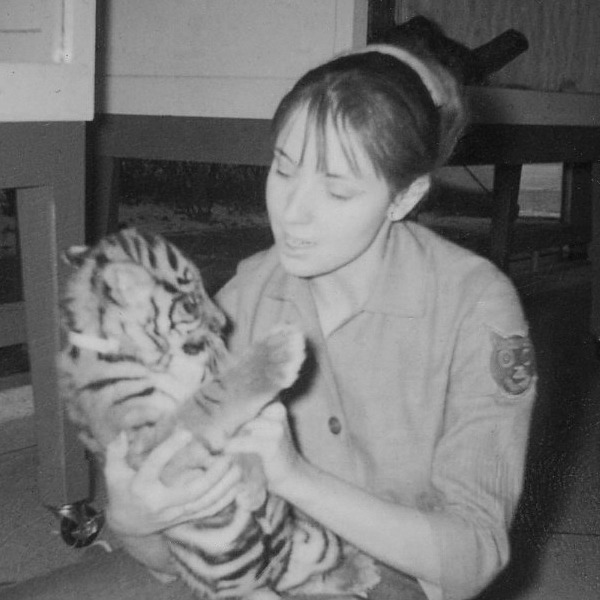

Well, there was young lady that I had come to know. I don’t even know where we met at this point. I can’t even remember, but we’d known each other a long time, and her name was Susie Reef. And Susie was at the zoo and Susie said to me, “Since you’re hangin’ out in the lion house, let’s see if we can’t get you in as a volunteer to start.” And so, she put in the word and I guess I passed inspection because I did have enough animal knowledge to be a useful volunteer, and I was willing to work the odd funny hours. And so, started out in the nursery and then eventually just kinda got bounced around wherever they needed me, but a lot of it was in the nursery because again, I was still going to school and I was trying to fit in my other paying jobs as well, because I needed the money (chuckles).

Were there are a lot of volunteers at the zoo at the time?

There were a handful and they were mostly older gals that were volunteering. And then there was the zoo attendants, like Pat that were working in the children’s zoo. And then I started, I liked reptiles. I think I liked reptiles ’cause the building was nice and warm anyway, and so, Eddie Armandarez would show me the reptiles and then I remember, as you spent a lot of time there with him when I wasn’t doing other things at the zoo.

So, as you were traveling around to these various places they would put you, were you doing keeper jobs?

I was doing miscellaneous keeper jobs, just kinda helping the keepers, carry the bucket, tilt the load, go check this, go look at that.

And what kind of zoo did you find when you first got there?

How would you describe it?

Well, I mean, to me at that point in time, it was this big, wonderful place. It was older, the buildings were older, but they didn’t strike me at that point of being, knowing what we know today, they didn’t strike me as being inefficient or inappropriate in any way. Yeah, I thought some of the… Having come from the dog kennel side, the big cat cages just looked like giant dog kennels to me. But I thought as long as you could give some stimulation to the creatures, it was what there was and I didn’t think one way or the other about it as being a good experience for the visitor or the public or bad experience. I just thought that’s what a zoo was. And you’re a volunteer. How did you work into a, “We’ll pay you money?” Because I was willing to do some night shifts and things like that.

And when they said, okay, but I didn’t get much money and I didn’t do it very often.

So, you can- you a paying position for a part-time job?

Oh, yeah, part-time ’cause again, I was in school the whole time I was there.

So, you’re still doing the same type of work, but yet, but now being paid?

Yes. Okay. And did you- It went on for a couple of years, but it was always part-time. And you mentioned that you also were working at the lighthouse with the signs. Was that part of your- Well, I wound up because it was in proximity. I would do anything that anybody asked me to do. And I mean, I volunteered to do the sign work, because somebody asked me if I knew how to use the machine and I said, no, I don’t, but if somebody would show me, I’ll do it. I loved the environment.

I just was happy to be at the zoo, you know?

And so if they told me, go out and rake the lawn or sweep the sidewalks, I said, “Fine, whatever.” How did this time at Lincoln Park Zoo, you said you were studying to be a mathematician, influence your career decision to work in zoos?

Well, I was, I guess I’ve always been a very pragmatic person. I was studying to be a mathematician because I knew I could get a job. I didn’t ever think I could ever get a job in zoos, or I wasn’t even sure if I wanted to be in zoos. I knew I wanted to work with animals. And I also knew I didn’t want to be a veterinarian because that was usually the career choice, “Oh, I wanna work with animals. I’ll be a vet.” Well, I knew I didn’t really wanna be a vet. I didn’t think I was cut out to be a vet. And I think that said to this day would be true ’cause I wouldn’t have been a very good vet, ’cause I got too emotionally involved in the patient and that would be counterproductive, but I didn’t know what else I could do in animals at that point.

So, I always thought it would probably be a hobby at best, because again, I knew I had to put food on the table and support myself. So, my undergraduate degree, which was going to be in math was the way I thought I’d support myself. And then from there I could go, maybe I’d go into the park service. I didn’t know what I, I just knew had to have something with animals and nature.

So, do you have any specific memories of Lincoln Park Zoo, the people, things maybe that were unique that you were allowed to do that you think fondly of?

Well, I mean, a lot of the babies that I helped raise in the nursery gave me wonderful experiences, and bottle raising things and watching them grow up and having some satisfaction that I helped these little creatures grow and we’d have a lot of fun. I also remember thinking I’d been killed by Frank, the baby gorilla, ’cause he decked me one day in the nursery, right onto that terrazzo floor. And I thought I was dead and he thought I was dead. He thought he’d killed his mother. And he was screaming and I’m laid out on the floor and the public is looking at me and they’re thinking, “Is she really okay?” And I’m laying there thinking, “I have to get off this floor. I have to find out if I can even move.” And so, I’ve fond memories of a lot of the little critters that we raised, and then pranks we would play on each other, occasionally. Eddie was a good prankster and- Give me a prank you remember. Eddie froze a…

We had a Cobra die. So, Eddie went through the misery of taking this Cobra and somehow freezing it into a striking position, and then he put it in the refrigerator and when you opened the refrigerator, you were met by a striking Cobra, which caused a lot of consternation among people when they open the refrigerator, to say the least (chuckles).

Was Eddie one of, or who were your mentors?

Eddie was definitely, took me under his wing. And ’cause he saw I actually really liked reptiles. I mean, I liked furry things, but I also really liked the reptiles. And so, and again, I was the only, I was there at odd hours of the day and night and I probably wasn’t there more than 10 hours in any week because of school schedules and this and that. So, but I always remember him most fondly. You mentioned that you had a little mishap in the nursery with Frank. He must have been, if he was a nursery, a smaller gorilla.

How did that occur?

Well, he and there was a young female that had come in, Debbie, but Frank was probably about two years old, so he was maybe 24 inches tall, but he’s just a little ball of muscle and he was out having playtime on the floor, and he had gotten into, discovered that if he climbed his little play chain up towards the ceiling, he could reach the light bulbs, and if he could reach the light bulbs, he could squish the light bulbs, and cause consternation to say the least. And so, he was on the floor and he was eyeing the light bulbs. He was looking up and looking at me and looking up, and I, without much thought sort of wagged my finger at him, reached out and I said, “Don’t you do that,” and he grabbed my wrist and he was below me, of course. He grabbed my wrist and flicked me over his shoulder. And I literally went flying through the air and landed on the terrazzo floor. And I thought for a second that I might’ve been dead, and then I thought I might’ve broken every bone in my body. And I remember amongst the volunteers in there that our job was to smile and show no blood because a lot of times these bottle babies would nip us and this and that and we were always to remain composed, even if we were being decapitated or chewed on by something. And so, I’m laying there, I’m thinking, “I’m not supposed to scream or yell, I’m not supposed to yell for help.

I have to figure out how,” and he was screaming his head, and he was scared to death. He had suddenly in his mind murdered one of his mothers. So, I knew I had to sit up and so I finally sat up and comforted him. And meanwhile, I’m wiggling my toes and wiggling my legs to see if it’s all gonna work, and then I’m going to see if I can get up because I didn’t even have a radio on. It was sittin’ on the counter.

So, I finally got up and crawled quietly, went over to the radio and said, “I think somebody better come over here and give me a hand for a minute.” Who was the director at the time?

Les.

Was he a new director at the time?

Yes, he was fairly new ’cause Marlin had just left for St. Louis.

So you never worked for Marlin?

No. No.

Now you got your degree in mathematics, correct?

Well, it wound up to be in computer science. That’s a whole different story, but I got my degree from Loyola, yeah. Undergraduate degree and then I left town. I actually didn’t even stay for the ceremony of walking down the aisle and getting the piece of paper. I said, “Mail it to me (chuckles).” Back up.

How did you change?

Why did you decide to change?

I actually didn’t decide to change. As you’re aware and I assume still is, Loyola’s a Jesuit university, and at it had just become co-ed a few years before I entered it. And I took my first math classes there at that level of junior level. So, and it turned out that that class was being taught by the head of the math department who was a Jesuit priest. And I was always good in math, but I couldn’t pass a test of his. I just couldn’t pass one. And I kept getting Ds and virtually, nearly failing grades on tests and I could not figure out what was going on because my answers were correct. And so, I went into him and I said, “Father, I don’t understand why I’m getting these grades.

My answers are accurate.” And he said to me, “Loyola has never graduated a woman math major, and you will not be the first, so I would suggest you change your major because in order to graduate as a math major from Loyola, you’re going to have to pass my classes and you’re not going to pass them.” So, I thought about that for a little while and thought to myself, “Well, I only have two alternatives here, three, I guess. I can quit college altogether, I can go find another college or I can change my major.” And so, I changed my major. And so, I went into computer science and at that point I just needed a major to get done, to get out. And so, I did computer science and education, which, ’cause again, I figured I could eat either way. So, you graduated.

What was your next move?

Well, my next move was the day of my last final exam, which was in the winter. I didn’t like school. I never liked school. I didn’t like high school and I didn’t particularly like college. They were just things that I had to do in order to be a productive member of society and to be able to work. So, I got out of high school in three years and I got out of college in three and a half years ’cause it took me an extra half year because of the major change. So, I was 19 and a half when I finished college and I was graduating in the middle in December, and it was doing what it always does in Chicago in December, it was snowing. So, I didn’t wait for the graduation ceremony when I had my last class and my last final and I knew it was done, the car was packed and I drove to California and I had enrolled in a graduate program at the University of Redlands in what would today be called, well, either conservation biology or something like that, but at the time it didn’t exist as a title.

So, I basically enrolled in Loyola in what was a biology major, but I got really lucky and had a major professor that was a young herpetologist and we clicked really quickly. So, we created, I think I was the only person majoring in what I was majoring in in the whole university because we kind of handmade it for me and everything that might have to do with things that might be useful in conservation, whether it was taxonomy, animal behavior, ecology, and those sorts of things.

How did you decide on California?

I had an aunt and uncle that had retired out to Southern California. And when I was in my, between my junior and my sophomore junior year of college, sort of, they gave me the money and flew me to California. If I couldn’t drive there, I had never been. So, I’d never been that far before. And when I got to Southern California and then they took me out, they wanted to know where I wanted to go and I said, “I wanna see the desert.” I’d never seen desert before except in movies. And I just loved the desert when I got out there and I said, “Okay, this is it. I’m pre-adapted to this environment. I love the environment.

I love the whole thing.” So, it made sense to me as soon as I graduated, I could finally get out of Chicago and the winter and the snow and the rain and go to California where it doesn’t snow and rain much. And so, I started planning for that in the last two years, year and a half, I was in Chicago. So, I found a university that would take me. And so, I basically drove out and went right back to school. The studies you’re doing seem more neutral. Right, because I figured now I had a degree already that I knew I could eat. I knew I could… I still knew I could even still be in a, I couldn’t be a certified public accountant or anything like that, but I can run the numbers.

So, I knew I could do that. I knew I could program computers and I knew I could teach. So I thought, now I can go get my degree in what I’m interested in. Even if I’ll never maybe be able to work in a field like that. So. So from 1967, through 1970, you had a wide variety of jobs, ranger, programmer, park ranger. Yeah. For Joshua Tree National Monument.

And naturalists traveling with junior high students for a month. Tell me about the junior high students.

How did that kinda start?

Well, I was, yeah, I was teaching junior high mathematics in Palm Springs and on summer, one of the other teachers and I decided to put together this field trip to take the kids out fossil hunting. And I mean, when I look back at it and I think about it periodically now, I mean, we would no more do that today, I mean, legally and every other which way, the responsibilities that we took on, I mean, we just rented some station wagons from Hertz, threw all these kids in it with a bunch of tents and went off and their parents let us do it. I mean, it was just shocking when I think about it and we brought ’em all back alive, which there was a couple of moments that we’d actually questioned whether we would, because we got into some bad storms and floods and ’cause we were in the middle of nowhere with these station wagons, but we were young and we did it, and it was fun.

of activities you were doing there?

We were fossil hunting. So, we were going to all the big fossil sites and at that point, I mean you could go out and dig around. I mean, a lot of these sites weren’t even protected and we’d go to various museums and we were camping the whole time. The whole time we camped. We had one kid break his arm and we’d take him in and have him, and his biggest concern was we were gonna make him go home and he didn’t wanna go home with his broken arm (laughs). So, it was pretty good.

while you were doing this about kids and maybe connecting them with nature?

That kids, if you got them out, after the first couple of days of sort of complaining that they didn’t have, of course the kids didn’t have then what we have now for kids anyway. I mean, mostly they would miss their TVs or goin’ to the movies because there was certainly weren’t computers and all that stuff. But once you got ’em out in there and got ’em into the swing of things, their whole requirement’s changed. I mean, the mugs that they were drinkin’ there didn’t have to be as perfectly cleaned as they were at home, and that they could actually put up a tent and enjoy it and this and that. So, they’re pretty malleable, even as junior high students. And of course these were kids whose parents cared enough to do this kind of thing for ’em as well. I mean, we didn’t do it for free. It wasn’t a lot of money, but probably was at that point for those parents.

You’re learning anything about keeping the attention span of a very young active group of students?

It didn’t seem to be particularly hard, and I’m not particularly the world’s greatest person when it comes to kids and this and that. It’s not that I, I just wanted a chance to get out and see all these things and to share it with the kids. But it just sounded like a fun thing to do. It wasn’t something where I’ve just was determined to take young people out and share the world with them. It was more, let’s go do this kind of fun thing. Tell me a little about the Joshua Tree National Monument.

How did you get that kind of a job?

What did you do?

(laughs) Well, I mean, that’s where I had wanted to work initially. I thought, I’ll be a park ranger. And so, I applied there and at that point in time, the various parks and monuments had their full-time staff, but during their busy seasons, they were allowed to hire locals as seasonal help. So, you didn’t have to go through any central agency in the park service. You didn’t have to apply in D.C. for a park service job if you wanted to be a seasonal employee. And so, I took, I said, “Okay, again, I have to eat, so I’ll do a seasonal employment.” And so I did weekends during the peak season and because I was teaching school during the week. So, I would drive out from my teaching job on Friday afternoon and where I was stationed at the park was about an hour and a half from where I was teaching school and living.

And they had a trailer just a little long, 25 foot long, eight foot wide old travel trailer that I lived in during the weekends at the southern entrance of Joshua Tree. They had two, three residences out there, stick-built residences for the permanent staff, and two rangers and a maintenance man, ’cause this was, there was nothing. We didn’t have telephones. We didn’t have electricity other than a generator to power all of this because we were sittin’ in the middle of nowhere in the desert. But, so I had the trailer on the weekends. So, I did a little bit of everything. I mean, basically I was hired as an interpreter, but I also did patrols and so between doing campfire talks at night and leading nature walks, and then doing patrols and it was, yeah, it was an interesting life and I met a lot of other rangers over time and I met mostly guys, young guys that were trying to get in full-time or who were permanent seasonals, and they just went to different parks at different times of the year. One guy would spend his summers at Denali and his winters that Oregon Pipe, and he just moved to wherever the park service sent him.

And so, I looked at that as a possibility of a career. So, I certainly enjoyed being out in nature. And I enjoyed showing people the flowers and the snakes and the lizards and all those kinds of things.

Were you learning things that would stand you in good stead later on in your career?

Certainly interpretive things about how to, what people that didn’t understand the environment, how to help them see the environment, and since it was desert environment and that’s what I was interested in. I think I, I certainly learned a lot of hands-on interpretation, which when I started designing Living Desert and its exhibits, I think helped me visualize what might be the best way to help people understand that environment or at least introduce that environment to people.

Can you give me a specific or an example of that?

Well, I mean, for most folks that would come at that point to the Monument, and then ultimately when they started coming to Living Desert they would arrive and they might not even want to go because it’s a desert and what could possibly be out there?

There’s nothing out there. And that what’s ever out there is either gonna poison you by being a rattlesnake or stab you by being a prickly plant.

I mean, other than that, what’s out there?

So, how could you have a whole monument or how could you have a zoo around a desert when there’s nothing out there?

And so, just waking people up to the knowledge that there’s a lot of stuff out there and that it’s really highly adapted to be out there, and trying out different things while I was in the park service in terms of interpreting that to people, and just seeing what worked the best in my eyes when I’d be trying to explain the environment or take people on a nature walk or whatever, I found that just making them stop and actually look, look straight down at their feet and start showing them that within 10 feet of where they’re standing, there’s 40 different species of little plants, but they gotta look at ’em. Like, they’re not gonna slap ’em in the face. They gotta get on their knees. They call ’em belly flowers for a reason, you’re on your belly to look at ’em. But and people would certainly go, “Oh my God.” So, things like that.

So, some of these techniques you were able to transfer over?

In the summer of 1970, you traveled 10,000 miles to study nature reserves?

Right. Well, by that point, I’d been hired by the Living Desert. That in itself was kind of an interesting piece of luck, although I always tell young people, you make your luck to a certain degree. You gotta have some luck, but you can’t stay at home waiting for luck to strike. You have to be out being there. And my dear friend, Susie Reef, had moved to Tucson after leaving Illinois and we had always stayed in contact and I used to go over and visit her. And she knew Bill Woodin, who was at that time, the founding director at Arizona Sonora. And so, we would go over there frequently and I loved that facility.

I thought it was everything a zoo could be in terms of interpretation. I mean, it was so far and so different and so far beyond what zoos were in my mind, that it was the catalyst for, there were two catalysts organizations and people that led me to build the kind of zoo that I wound up building. And one was the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum from its focus of just immersing you in the environment that they were trying to teach you about. And then one was Gerry Durrell who said, “Zoos need to be breeding endangered species.” And I took those two thoughts and eventually meshed them into Living Desert, but backing up, I was absolutely enamored with Arizona Sonora Desert Museum and what they were doing. And I got to know Bill Woodin well enough, and he offered me a job if I’d come there and be a graphics artist for them. And I said I would do that as soon as I finished my teaching contract and the folks that were looking for somebody to start a nature center in Palm Springs went over to see Bill Woodin and said to look at Arizona Sonora Desert Museum. And the first thing they said to themselves at least was, “Well, we’ll never build anything like this. This is way too big,” but they still were out looking around at nature centers in their minds and they happened to ask Bill, he said they were looking for somebody.

And he said, “Well, it’s kind of odd because I’m bringing somebody here that lives there (chuckles). Why don’t you go back and talk to her?” And so, they came back and found me and talked to me about starting a nature center. And I didn’t know quite what to do about that at the moment.

And so, I drove over to Arizona and I sat on the floor of Bill Woodin’s house on his floor and I said, “What on earth should I do?

I don’t know anything about starting a facility from scratch.” And he said, “Well, I was a young herpetology student just out of college when I got the job at Arizona Sonora Desert Museum to help start it at scratch.” He said, “I didn’t know anything either. You’ll figure it out.” So, I went back and took the job.

So- They hired you as what?

The only employee and I was, my first title was Resident Naturalist because my first job was to help raise enough money to put a small building on the property that they had leased. And I was supposed to live there and interpret the property, just be like a park ranger out there. And so, but at that point, there was no buildings. There was nothing. It was just the acreage that they had leased, which was in the middle at that point of nowhere.

And this was called the Living Desert Project?

At that point it was called the Living Desert Reserve. The local individuals that had started this were very well connected in the little community of what was Palm Springs at the time. They actually went to the Disney family who had a home in Palm Springs, got permission from Disney to use the name, Living Desert, because of the movie. So, we actually have the legal right to use the words Living Desert as part of our title. And they had leased some land from the local water district because it was all flood plain at that time. And so, they had leased the land and they had a name and that was it. And it was in the middle of what, at that point was 18 miles outside of Palm Springs. And the founding founder, Mr. Boyd, owned a bunch of property in that same area, but not this particular property.

And so, but he liked this particular property and that’s why he was able to get it leased from the water district. He was very well connected and our water district is, in the desert your water district is probably your biggest public agency. And they have all the power, what they say goes. And so…

What year was this?

He had leased the property in 1968, I believe, but they were looking for somebody, they started looking for somebody to actually work there and put enough money together to hire somebody in 1969. So, I was being interviewed in the end of 1969, and I was hired in March of 1970. And that’s what led to the trip is I said, “Well, I would like to spend the next few months looking at facilities, looking at everything from national park facilities, to zoos, to nature centers, to natural history museums. I just wanna go out and see what’s out there. And so, they gave me $800 and said, “Don’t spend it all on the same time,” and I lived in my car and you can go a long way with $800 if you were living in your car at that point in time. And I visited and I kept notes and took photographs of… Never ventured any further east than Eastern Arizona. So, mostly it was Arizona and Utah and places like that that were more desert-y.

What were you discovering?

I was discovering that there were millions of ways to do interpretation, and that most of them seem to be useless to me. I would look at zoos and I’d see some terrible exhibits, and I’d go into the park center buildings and they had a lot of panel type exhibits and some of them, most of those weren’t very engaging and nature trail signage was all over the map, but here and there, I would run into people or exhibits or ideas that said, “Hm.” So, I’d take lots of pictures of those and to remind myself and lots of notes, which is, and I came home with lots of ideas of what to do. And so, and youth. If anybody had told me that 40 years later when I left that I still hadn’t done everything I thought I was gonna when I first started 40 years, I probably would’ve never started, but you don’t know that. That’s the joy of youth. You think you’re gonna do it, so you just set off and start doin’ it.

How did this trip shape your views on nature or zoos responsibilities?

I think, I don’t know if this trip per se didn’t shape the zoo’s responsibility part. That part, I think really just clicked in an instant again, when Gerry Durrell started writing his books about setting up first his little animal collection books, which were all hysterical and funny and this and that, and that’s all they were, was hysterical and funny.

But then when he started getting a little more serious, and I went, yeah, that’s what zoos ought to be doing is besides just having one of everything because I mean, we really did rank our institutions with, “I’ve got one of these, you don’t have one of those.” And Jim Dolan and I used to laugh as we got a little older that at that time a collection plan was if the director knew anything about animals and some of ’em did, many of ’em didn’t, but was do I like it and is it pretty?

That was the collection plan. And so, zoo director of zoos looked quite different one from the other depending on the director and whether he liked it, and wanted to put it in his collection. And I kept thinking there has to be a better reason, I mean, than just, “Oo, ah, I have one of these and nobody else has one.” And it all clicked when Gerry Durrell said, “Yeah, we don’t need one of everything.

We need to take care of the ones that need the help.” Did this trip cement your love for deserts?

Yeah.

How so?

I actually always felt like once I actually got physically on a desert in the junior year of college, it was like, that’s where I was supposed to be. It just, it was an environment that just spoke to me immediately that there wasn’t any, “Gee, I kinda like it,” it was like, this is it. I think if my aunt and uncle had lived in Tucson, that desert is extraordinary. And if they had lived there, that’s where I would have started, but they lived in Southern California, so I’d never seen the desert in Tucson at that point. I’d just seen Southern California desert, which is much harsher. It’s low Colorado Desert. It makes Tucson look like a jungle. And so, but it was desert and it’s still the vistas and the dry air and the warmth and being able to see, now I live in forest again, but in the desert, you can see nature, it’s all there.

There’s no trees in the way. And it just spoke to me immediately, immediately. And you mentioned that, I believe it was Mr. Boyd had purchased this land. Oh, he leased it.

He leased it?

Mm hm.

Why did he want to create the Living Desert?

He was an interesting man. He was from the East Coast, but he’d moved to California for health reasons when he was young. He was a banker, a land developer, and he also was interested in education and he became a regent with the University of California. And he too loved the desert in his own way. He didn’t know a lot about it, but he knew his land developer institutions tuition said the Coachella Valley where we were, it was gonna be buried in houses someday. And there ought to be a place where people could learn about the desert. And so, he envisioned creating a nature center. He also gave a big chunk of land that he had purchased to the University of California system for postgraduate research only.

And it’s still operating that way, in the same floodplain that our facility was in. So, he was a great believer in educating people, but he just loved it. He had his own reasons. Maybe it just spoke to him the same way it spoke to me. He never studied it. I mean, he knew a few of the plants upon sight and he knew a few of the animals, but he wanted to support research into the desert environment and he wanted a place to have people come and learn about the desert. So, in his vision, it was just gonna be a desert nature center. In my vision, when I saw it, I said to myself, this can be so much more, but I better not say anything because they’ll think I’m crazy.

So, I never, I just gave them their vision and then I just added a few things as we went along, and as long as I added them in a way that seemed to make sense to them and I got them paid for it was all right. So, the vision very slowly expanded without much resistance because I could make it happen and they kinda liked the results. Now he couldn’t do this alone. He must’ve had- And there were some other wealthy folks. The desert, you could not have done this project in Bakersfield, California, or some little town somewhere, but you could do it if you were cautious and careful in near Palm Springs, because for a few months out of every year, there was an inflow of money, moneyed folks. Now, 99% of them had no interest in spending any money, including donating any money in the desert because they didn’t live there. They lived here, they lived in Chicago, and they lived in San Francisco, or they lived in Seattle. That’s where most of the money folks would come from, or ultimately from Texas, they’d come in from Texas as well.

So, it wasn’t easy to raise money there, but there was money there and there was, Mr. Boyd had access to it because he was first mayor of the city of Palm Springs and so forth and so on. So, and he had a good reputation, and so his friends would follow along and chip in just as donors do today. If their buddy has given to somethin’, maybe they’ll give a little bit to it too. And I turned a lot of water into wine, but I was good at that ’cause that’s how I grew up. I had to turn a lot of water into wine because I had to, to live and feed myself and go to college. And there was no such thing as a loan. We never took a loan at Living Desert to do anything. I either had to have all the money in place or we didn’t do it.

Who were some of these other movers and shakers that your remember?

One of them, I still see. She’s 100 years old and she lives in Glencoe. Miriam Hoover of H. Earl Hoover of Hoover Vacuum. His son, Bud is still on our board. H. Earl had a winter home in the desert and he was on my first board and stayed on the board until he died. And then Miriam came on the board, and she stepped off the board about three years ago and now Bud’s on the board, and I just had lunch with Miriam for Easter at 100 years old. And she lives, yeah, she lives right on Green Bay Road in an ancient estate sittin’ out there. So, they were very active.

There were a couple of people associated with the University of California system in the Life Science Department that one of which had a lot of money himself, but he was also, he really was, he liked to think of himself as a field biologist. And so, he got involved. And so I had, because Mr. Boyd was a regent to the university, the local camp was to us was Riverside, which was about an hour and a half’s drive. So, all of the ecologists and herpetologists and botanists that were based on that campus teaching, and were using Mr. Boyd’s research center for post-graduate work, he convinced all of them to help out wherever they could with scientific knowledge or whatever I needed. And so, I could draw on the science, I could draw and Mr. Boyd’s friends and connections, and then I just went on the trail of going to every rotary club, every lions club, eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner with those guys and fundraising. And I would stand there ’cause I was young and committed to the project and tell ’em, they’d say, “Well, what are you going to do?” I’m saving the desert and they’d look around, there wasn’t a stick out there, there wasn’t a house for miles. And they’d kinda go, “From what?” But they’d humor me, give me a few bucks and we’d go to the next step. You mentioned when you started, there was this vision that Mr. Boyd had, but you had a secret vision that you didn’t wanna share.

Right.

What was that secret vision?

To create what we created ultimately, a desert conservation center where we taught people about the desert, the whole ecosystem. So there was kind of the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum model, but instead of just modeling Sonoran Desert with plants and animals, I said, “Well, okay, that’s been done.” And to just modeled the Colorado Desert, the Coachella Valley, that’s a pretty limiting experience. There is not much out there compared to Sonora. So, I thought, “Okay, we’re gonna do deserts of the world,” and I was able to say that kind of out loud once we started doing interpretive things, because that kind of made sense to the board. Well, okay, so Mr. Boyd loved plants first, and nature trails. So, I just gave them what they wanted first ’cause it wasn’t, I didn’t have to do either or. I mean, I wanted to do the plants as well as the animals. And I wanted to do trails.

We had at that point 400 acres that they had leased. And so, I never had to refuse to do what they wanted to do. I could just incorporate what they wanted to do into my vision of what needed to get done anyway and just do what they wanted first, and then kind of slide the rest of it in as we went. So, I never used the word zoo. Even though I was already extremely active in the ACA we weren’t a member because my board didn’t consider us a zoo. So, I never actually, the institution never joined for many years (chuckles). Now, you told us about your first title there.

How did that evolve into president and CEO and what’s the difference?

There really wasn’t any. I mean, for the first two years there was just me. So, and so I’d just get up in the morning, look in the mirror and tell myself, “This is what you’re gonna do today and go out and do it.” But over time, as we did develop a staff, a few people at a time, one at a time, two at a time, eventually they decided that I could be the director. And I carried that title for a long, long time, and then somewhere along the line, I can’t even, frankly, at this point remember when, we changed to, I think a lot of the boards were changing and their directors were now called the presidents and their board members instead of being presidents were chairman, and so we just evolved to that. I never, it didn’t make much difference to me.

After you had done the, what I guess I’ll call the basics of what the board wanted with the trails and so forth, did you have any things that you knew you wanted to develop first?

Well, yeah, absolutely. I mean, I knew I needed to bring animals in because if we were gonna make money, the kids weren’t gonna come to see plants and hike. ‘Cause again, Colorado Desert’s pretty barren even at its best and so I said to the board, when we designed our very first building, I said, I’m gonna design some small animal units like you saw at the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum for lizards and kangaroo rats and ground squirrels and snakes. And he said, “Oh, okay.” He said, “Okay.” And I said some desert tortoises and an exhibit outside the building and, “Oh, okay.” And then as part of those, right then back in 1972, I said, we’re also, I said, I wanna show people, begin to make people understand that these animals look the way they look, and these plants look the way they look because they’re living on a desert and they have to do, they have to evolve to live in that environment and whether you’re in a desert here in the Coachella Valley, or if you’re in a desert in the Sahara or in the Namib, your plant’s gonna have structurally very similar and an animal’s gonna have to structurally be very similar. And I said, “So, I’m gonna bring in a few of those.” “Well, okay.” And so, from the day we opened the first big animal exhibit in 1972, we had jerboas and kangaroo rats. And we had some euphorbia does that look like ocotillos, and they were shaped like ocotillos but they were euphorbia’s from Africa. And so, we started doing comparative and nobody really thought about it. I knew where I was going, ultimately, which is bigger and better every day, but it seemed to make sense.

I could explain it to the board that it’s why we’re gonna have this, these funny little animals that don’t live in our desert, but they live in another desert. “Well, okay.” Made sense.

Did you have a master plan that you had to show them or that you wanted to show them?

I had a master plan, I had two master plans. I had the master plan they saw, and then I had the master plan that underlaid that master plan that they didn’t get to see for about 12 years. In all honesty, they never saw it. The master plan they saw was exactly fit. It was a big piece of my puzzle. So, they saw the piece of the puzzle that made make sense to them, which was all the North American gardens, desert gardens and so forth and the trail systems, and a small animal building. We had evolved to the point where I thought they could eventually, although they didn’t know what the building was, they just saw this building on the plant and I used to say, “Don’t worry about it. We can’t afford that building anyway.” And then there was another master plan that this would sit on that I was aware of that I was headed towards and I just knew at some point I would tell them what the next phase was when I thought they might believe me.

Who was helping you develop the master plan or was this all your vision?

I guess it was me. I mean, it sounds rather pompous, but it was just me based on visiting zoos, visiting parks, and thinking about how I could teach people about the desert and how I could afford to build certain things, because again, I couldn’t build it unless I could fundraise for it and I had to pay for it. And so, trying to figure out inexpensive ways to do certain things that would still be professionally appropriate because I knew there wasn’t a lot of money. Were you going to the board and saying, “I need this type of money to do this on the plan that you’ve approved?” No, usually it was kinda the other way around. I would design something and then I’d figure out what it was gonna cost to the best of my ability.

And then I’d go talk to a couple of different board members about, do you think this is a good idea and would you help me fundraise for it?

And then once I got all the pieces in order, then we’d take it to the board and go, okay, on the master plan, this is the next thing, and Karen says it’s gonna cost us this, and we think we can get the money here and the board would go, “As long as you get the money, okay.” Give me an example. Coyote exhibit was probably the first… Well, yeah, it was the first large animal exhibit if you can imagine a coyote being a large animal, but in the desert, that’s a large animal. And I put it way across at the other end of the park and there was nothing in between except some nature trails. And some of the board members were like, “If you’re gonna put in a new exhibit for coyotes, why don’t you put it up close to the buildings?” ‘Cause in their minds it was, we had all this acreage but, and I said, “Well, no, coyotes need certain kind of behave, and they’ll be fine, it’ll be fine.” And people can walk out there to see ’em and… But I had to figure out how to build it and I never had a general contractor. I just decided that to this day, if I need to get it done, somehow I’ll get it done. And you can be an owner/builder.

To this day you can be an owner/builder in California. You don’t have to have a general contractor. And so, I just learned to be an owner/builder. And so we could build stuff that a lot of people couldn’t have afforded if they’d just done it the traditional way, which is go out, gets bids, have some general contractor come in and do it. I would call, if I needed a block wall built, I’d call the block wall guys and go, “Okay, how much is it gonna cost to do this wall?” And if I needed a building built, I had an architect that would work pro bono for us, and he would draw the drawings and then I would go to the electrician and be, “Okay, how much is the wire?” I just wound up being an owner/builder ’cause I could get things done cheaper. Again, well, turn the water into wine. Were you for this coyote exhibit, as an example, did you have the money in place before you did it or were you building it- No, I had to have the money in place. So, I had to come up with a design and I drew the designs and anything I could draw designs for as opposed to paying an architect, I would draw ’em.

So, I could draw walls and I could draw landscape features and I could, because there was no structure to that. It had a little house for the coyote so the architect was, the pro bono architect, John, would draw that and we’d get a permit stamp from that. And again, we were kind of in the middle of nowhere, the city said, okay, but all the rest of it, I would draw myself and then we would build to those drawings.

Did you have any, as you’re developing your master plan, was there any friction with the board or people who wanted to go in a different direction as you started to develop things?

There was hardly any friction about the plan. There was, because we had a lot of ground physically available to us and the community was just starting to grow around us, we had other organizations coming to us and asking our board can’t you lease us X amount of ground. We wanna put in a lawn bowling.

I mean, that was my favorite one is I had a group of fairly wealthy people who decided they loved the lawn bowling and there was no place to do lawn bowling in the area and so, and we had all these acres, couldn’t we give them a couple of acres to do lawn bowling?

And I’m going, “No.” And my board’s going, “Well, why not?

We have all this anchorage.” And so, I had a few incursions like that, that wanted to use the land for something else.

IMAX came and thought they might wanna put an IMAX and did we want an IMAX on our property?

And this is before, I mean, there was nobody out there at night. And I thought to myself, every IMAX I knew at that point was a money losing operation for somebody. So, I had those kinds of things, but ’cause I moved very slowly, and I tried not to offend ’em and I tried to give ’em what they wanted. And mostly I had to balance the budget every year and we had to make money every year, period.

What kind of budget did you start with?

My first budget was 10 grand, and please don’t spend it less than, in 12 months, ’cause you were gonna run out of money in 12 months and that included my salary. And when I think by the time when I first sat down and had my first lunch with Bill Conway and he was talking about having a budget of millions of dollars, and I think my budget then was 25 grand. And I just kind of looked at him thought, “Have I ever had a million dollars to run the place, I wouldn’t know what to do first,” but then it just grew every year by what we could make. Not by what we were given, but in terms of donations, but what I could generate through teaching classes and visitor, the ticket booth, and a little gift shop, I put a gift shop in right away.

So, your income was coming from a couple of sources through your four?

For operations, yeah. Memberships, gift shop, admissions, classes.

How were memberships received?

Pretty well. I mean, it was slow slogging. I mean, we started the first year we had 70 members or something like that and every year it would grow a little bit, but it was tight. It was really tight, which is why for our first couple of years, there was just me. And I learned how to drive tractors and use skill saws and routers and made signs using the old technique of the sign cutting equipment. Just did it all. I mean, we didn’t buy anything that I could make.

So, you were the only full-time employee?

For two years, yeah. Was it easy going from a small salary ’cause you obviously built the facility where you were dealing with six figures or more. Was it hard to do that or it just- It just evolves. It’s evolved. This is like growing up. I mean, every day you’re just a day older and you get a little older and you get more life experiences and it just happens. I mean, it was a very purposeful happening, but it was a happening. I mean, you just took each day and some days you went backwards and wondered why you were doing what you were doing and…

What kind of disappointments were there in these beginning times?

Oh, I think that it was often tiring of just worrying about where the next dollar was coming from. I mean, that was always there, because initially most of the people in the area didn’t have any real interest in what we were doing because it was just the desert after all, but we got very lucky several times in the history of Living Desert, the organization essentially was able to grow and thrive ultimately, or reasonably thrive out of what turned out to be pure luck. I mean, when we started, the only land Mr. Boyd could lease for us was where we are today. But at that point it was 18 miles away across basically nothing but empty desert to get there. And there was no reason to get there unless you were going there, and ’cause everything that was going on in that area was going on in Palm Springs. Palm Springs was the hub. And so, for the first few years it was really hard because it was a big drive just to go out there to see what, in most people’s minds was nothing. But then the population in the valley started to creep in our direction and a big land developer of shopping centers of all things decided to build a shopping center, the very first shopping center to serve the area because Palm Springs was a strip of fancy streets, of fancy shops, and golf courses.

And that’s what was Palm Springs, and so to have a shopping center, and where does he put the shopping center?

Two miles from my park. And I mean, I could, I mean, at one point it was a big, it took our attendance dropped because everybody went to the shopping center. That was the new entertainment, but I could not have paid anybody to do that for us. But suddenly he shifted the whole, instead of being on the edge of nowhere, we were now in the middle of, in the valley, grew around us. I couldn’t have paid for that. And if that hadn’t happened quite that way, it would have made… And he did it fairly early on in our existence, in the mid ’70s and so, in five or six years into it, all of a sudden it wasn’t that far to go to this crazy place in the sand out there called Living Desert. You mentioned there were other major events like this that helped the museum.

One was an act of nature. In 1976, the water district owned the land. The reason they own the land was that it was a flood plain.

Ah, a flood plain floods, right?

The general manager of the water district was born and raised in the Colorado Desert down, and so he actually loved the desert and he was interested in it. And so, he stayed, the part of the reason he leased the land to us initially was because he thought that this would be a good thing for the community, and the land was part of their flood control land. And so again, in his mind, like everybody else’s mind, I was just gonna do this little nature center and, okay. We had to have a couple of buildings so that we could take care of the place and charge him. So, my very first job there was to go out with him, the general manager of the water district, the God figure of our area, and site where we could put two buildings safely on this flood plain. And there were all these levies to control water and turn the water to protect the cities from all the, just like you see in the movies, floods, because we had ’em. So, we were walking along one of these levies on this leased land with, this gentleman’s name was Weeks, Lo Weeks, and I’m walking with him and I’m just this little young girl half scared to death ’cause I’m walking with the God figure of the Coachella Valley. And I said to him, “Mr. Weeks, we need to put two buildings here.” We decided on two, as opposed to one big one right next to each other.

And I said, “Where can we put them that they won’t float away in a big storm?” And I said, “Where is the water gonna go?” And he looked at me and he said, “Young lady, I’m an engineer of water. It’s been my career.” And he said, “And I can tell you this about water.” And he said, “Water goes any damn where it wants to.” (chuckles) And I went, “Okay, so where do we put the buildings?” So he said, “Okay, we’re gonna site the buildings here and they should be safe. They should be safe.” So, we built the buildings where he sited them on this levee sign. In 1970, we started construction ’71, finished ’em in early ’72. 1976 tropical storm Kathleen hit the Coachella Valley and we had nine inches of rain fall in 12 hours. And we had a huge flood. It would have washed the buildings away. Flood water was flowing, the buildings sat on a levee and between the levee was one side, one containment for the flood water, not contained like hold back, but channeled.

And the other side was an actual part of the topography. It was a big ridge of mountain that came down and there was the distance between them was, oh, probably 700 feet of ground where the water from 25 square miles of desert mountains was supposed to go between this levee and that mountain ridge. And it filled the space between the us and there were waves lapping over my head, visual waves of mud and debris, and the mud and debris started lapping against the sides of the buildings. And then all of a sudden it went down and it went down because it broke through the levy above me. And it went through the little community that had grown up around us and filled houses in some cases all the way to their ceilings with mud. Nobody was killed, it was amazing. I mean, people, it was the most amazing flash flood storm one would ever want to live through, but it wiped out a lot of what I had already built. When it broke, it did save my buildings.

It wiped out some of my original gardens, wiped out all my trail system. Wiped out everything clean. It actually wiped out a fair portion of a toe of the mountain that it literally ate into the toe of the mountain. And we had big horn sheep on that mountain at that time and it took the fence down that was holding them in. And so, I had to helicopter over some fencing before the water went down and we hung some fencing up. The sheep fortunately decided they’d rather just stay at home than try to leave. But because of that storm, the water district, I would, at that point, I was only limited to what I could do on that property to about three or five, three or four acres, right on the supposedly safe side of the levee where the buildings were and then nature trails. That’s all they could do.

And when that storm hit and destroyed a lot of the town and a lot of the houses they destroyed were extremely wealthy houses, this wasn’t some flood in some backwoods farmland somewhere, the water district knew it had to do something to not allow that to happen again, so they built this huge levee that suddenly took my 300 acres and fully protected all of that, and allowed me to then create the final master plan because now all of a sudden, instead of having about 20 acres to work with, I had 300 protected acres that I could have never. I mean, it was a bazillion dollar job that we would’ve never been able to do because the district wouldn’t have approved it anyway, but we could never have afforded it. And all of a sudden they had to do it because of this storm that ravaged the town.

That still protects it today?

Yeah. Still protects it today. Mm hm.

Is the land still leased?

Yeah. Well, the original 300. We picked up other pieces over time. So we have about 1,200 acres that we control. We also, we leased a full section from the city of Indian Wells. We’re in two cities with the city line runs right through the facility. I actually built a building in which was built in both cities and had both cities trying to permit us at the same time, which is why I have more gray hair and less hair than usual. But the one city, we got them to buy some land from the Southern Pacific Railroad, and then they leased it to us, a full section, and then the water district lease and then we picked up some land.

So, we have a contiguous 1,200 acres there.

And it’s all leased?

Well, we own 300 of it and the rest of it’s leased. Long-term, just like San Diego, Suisun lease land, it’s just leased. And you mentioned you had this plan, your plan, and that there were certain animals of the desert you wanted to bring in.

Can you tell us something about the first animal or animals that you acquired that were part of that group and how you were able to bring them in?

Sure. Desert antelope ’cause I always liked antelope. I established a great rapport with the folks down at San Diego and particularly Jimmy Dolan, who at that point was curator of collections in San Diego. And they had just finished building the animal park, the wild animal park, and they had a bunch of odd kinds of things down there. They had slender horn gazelles and they had Arabian Oryx and just all bunch of different gazelles. And Jimmy kept saying to me, “You ought to have this stuff, you ought to have this stuff.” And I said, “You don’t understand. I’m not sure my board’s ready for that yet.” And, but I thought, “Well, okay.” So, I started talking to a couple of board members about we had all this space and I mean, instead of putting lawn bowling, let’s do something else with it. And we could help as if this was a new idea that just popped into my head.

We could help work with this world famous San Diego Zoo and help conserve this little antelope from North Africa called a slender horn gazelle. And we got the space. We could just out near where we have our big horn sheep exhibit, which is our local desert big horn, we could put it, and it was like, “Oh, I don’t know.” I said, “Well, we have jerboas and we have kangaroo rats, and we’ve got horn vipers in sidewinders, which are parallel evolution.” I thought, “Well, we can talk about desert antelope.” And, and there was, “Uh, uh,” and I said, “Well, can I invite Dr. Dolan,” Dr. Dolan, “To come down and talk to the board about this?” And Jimmy, as you may remember, could charm the pants off of anybody he ever met. So I said, “You come down.” I said, “You’ve been good and behaved well, James, but I need you to convince my board that this is a good idea.” And he came down and he came down as Dr. Dolan and didn’t he charm the pants off of the whole board and said that the world famous San Diego Zoo really wants to work with the world famous Living Desert on this project. And Jimmy, they bought it. And once I got my foot in, it was kind of like, well, we got the slender horn out there and then we did Arabian Oryx, and they found we could do that and they found the public kinda liked it.

Although a few people go, “Why do we have these strange animals that are not from our desert?” And we go, “Well, we’re saving an endangered species.” “Well…” Was your main focus dealing with San Diego and then you started to expand to others?

Well, I mean, I didn’t have to expand too much to others. I mean, we had a huge focus on botanicals because my founding board and Mr. Boyd really want, so we had a lot of garden focus. So, I was very involved in the botanical garden community in getting specimens from all over everywhere, because that’s, again, what the board felt most comfortable with. And I always gave them what they wanted first, as long as it wasn’t lawn bowling. And then, if they could humor me on what I wanted, but San Diego was a huge resource. I didn’t really have to go very far. I mean, pretty much I could develop my collections right off of what they were working on.

You mentioned plants, how hard was it to acquire exotic plants from different parts of the world?

Well, in California because we were in an agricultural area, there were a lot of legalities. So, a lot of material that we got, I would work with the various botanical gardens in California, where the material was already in the state, but we did and for a lot of our California gardens, we got permits to actually collect material and transplant it and build the gardens. But we took about four years to get permits, to bring plants up from Mexico to do our Baja gardens and our Sonoran gardens. And even some of those plants, I was able to work with botanical gardens and get seed stock from botanical gardens to start the gardens. So, it was always a challenge because we were just down, literally a few miles from us was the largest date. I mean, we were the date hub of North America for growing dates and a lot of truck farming and so forth. So, that department was always pretty careful. And still to this day, watches our plant material pretty carefully.

You had gotten the Boy Scouts involved with the Living Desert?

What was their job?

Well, they helped me build the first trails. They were the physical labor. They were out with shovels. I staked a trail system out and then they came out and Eagle Scouts came out with a bunch of younger Scouts and cut the trails and pitched the rocks and I had made all these steaks with numbers on them and the usual typical thing ahead of time so they came out and helped make little piles of concrete and stick ’em in the ground for me and so forth. So, we tried to keep the community involved any way we could, any way we could. Now, we had talked about your month-long trip, things that you learned on it for the Living Desert.

Did you start or think about then doing trips for the Living Desert would be involved with?

Well, we did a certain, yeah, right away. I mean, we did a lot of classes and we did a lot of local field trips. We did out to death valley and down to Baja whale-watching and we started doing trips right away because I really felt that that was a great way to get people involved. A lot of day trips, birding trips, hiking trips, wildflower trips during wildflower season, geology trips, because the valley is actually not a valley at all, it’s a fault trough. So, I mean, we would sit right on the San Andreas. So, there’s a lot of geology to look at. And so we did a lot of that. The park still does of course.

Who were you trying to reach in these trips?

I was just trying to build visitation. So, it wasn’t so much that, I mean, some of the bigger trips you ultimately might have gotten some of the donor types to go along. But for me, it was just creating a reason for people to want to become a member, to want to support the organization because I had to pay the light bill that way. I tried desperately to, I had to operate in the black every year or I had to cut if I thought I wasn’t gonna make the budget black at the end of the year, I had to start whacking at it before the end of the year got there. I couldn’t say, “Oops. We overspent by 10 bucks this year.” That was forbidden. So, anyway I could connect people to the park and birdwatching or field trips or whatever, we were gonna do it. One question that I was thinking about was you mentioned the botanical collection that you had to start with, or you were developing.

Would you say that it’s value so to speak, rivals or is comparable to the animal collection in the type of specimens you had to acquire?

Absolutely. The botanical collection, because the board again, felt most comfortable doing gardens first, we made a pretty serious effort in really doing a good job with specimen plants, well labeled, well-documented, and the second professional staff person I ever hired at Living Desert was a botanist horticulturalist position. I hired that position and I stayed curator of animals for many years after that, but I brought the plant position in first and we certainly have spent as much or more money on the plant collection from day one, as we ever did the animal collection.

And part of that vision also was this comparative between the plants of the desert and the plants of deserts around the world?