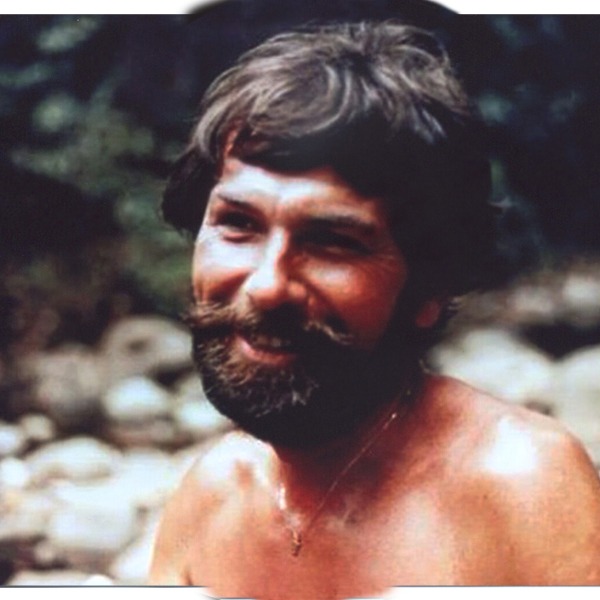

My name is Dennis Meritt. I was born in Rochester, New York, and it is the 7th of May, 2016.

When were you born, what’s the date of your birth?

Oh, date of my birth is May 17th, 1940.

What was your childhood like growing up in Rochester?

My childhood in Rochester was much different than most childhoods. I was the oldest of four children, four boys, God rest my mother’s soul. And we had freedom that children today don’t have. It was not unusual for us, particularly during the summer to say, okay, we’re out on an adventure and off we would go. And in that part of Western New York, we had lots of opportunities to interact with nature. The closest place was a vacant lot that was just down the end of the block. And we used to steal potatoes from home, build a fire and cook potatoes in the fire while we were chasing frogs and catching snakes and generally be doing what boys do. Were you a collector of animals at a young age bringing them home or was that all the brothers did it or no one did it except you, or no one did it.

Collecting animals was kind of intuitive to me as far back as I can remember. And I thought about this a little bit. I’ve always had this, not a need, but this knack for picking things up, for looking at things, for trying to understand nature and what’s in nature. And I don’t think, all these years later, I don’t think I’ve changed much because I’m still doing the same thing. I still have that, I tend to think of it as a gift now, to be able to see things and to want to understand more about them.

What did your parents do?

What did they do for a living?

My parents were, I think, typical parents for that age, it was just after World War II. My mom was a stay-at-home mom taking care of the boys. My dad was a production manager for an advertising firm in Rochester.

And what is your earliest memories of zoos?

Was it the Rochester zoo?

Did they take you there, did you go on your own?

My earliest memories were probably Rochester. That was the only zoo that was there. Occasionally we’d take a trip to Buffalo and that was the big zoo, but I believe that my oldest, earliest interaction with zoos was in Rochester at the Seneca Park Zoo. You found it fascinating or it was just one of your childhood things that you did. Oh, it was just one of those childhood things that we did. We spent a lot of time outdoors. The Seneca Park Zoo is, was and is located in a very large city park along the Genesee River in Rochester. There’s lots of hiking trails.

There’s lots of ponds and lakes. It’s essentially midland deciduous forest. And it was just a great place to go and to take a picnic lunch and the zoo sometimes was part of that, sometimes wasn’t. Also was a great place to fish.

Were there any animals that you were drawn to when you were at the zoo or that stand out that interested you?

I think the animals that I was most interested in early on before I really realized that I was interested in the profession were all related to reptiles and amphibians, if there was a frog or a toad or a snake or a turtle or a tortoise, it was right up my alley. And so whenever I had the opportunity to go to a zoo or to go to a nature center or to a wildlife reserve, I would look particularly for those kinds of animals.

Do you feel that your interest in animals started to determine a career path?

My career path is really kind of interesting. When I got out of high school, I can remember this vividly, I was planning on spending my entire salary just loafing after four years of education and my parents made it abundantly clear to me that I needed to go get a full-time job, something different than working at the corner Italian grocery store. I had to generate some funding if I was gonna live at home. And so I searched and searched and searched, and I actually interviewed at a general hospital and I was very proud when I came home and I could still remember this day, I was very proud that I came home with a full-time job. And my first paid full-time job in life was as a morgue attendant at Rochester General Hospital. And I can remember announcing as mom was getting dinner ready, that I was the new diener, so to speak, in the morgue in the hospital. And she flat out passed out and literally my dad had to catch her before she hit the floor, because she couldn’t imagine anybody would take a job like that. So after high school, you didn’t have college thoughts.

You were getting a full-time job. I was getting, after high school, I was getting a full-time job. College wasn’t even an option. It was all related to dollars and cents. And so I went to work. I worked my way through the general hospital from being a morgue attendant to a histology technician, to a lab tech for bacteriology, had a little time in medical photography and then was, and then became the special projects technician for the pathologist, who was a very famous pathologist, and for a time was the Cook County medical examiner, Milton Borod. And I did that for probably five years time. And during that time he encouraged me to continue my education.

Yeah, did that progress?

With his encouragement, and given that I had done everything I could possibly do at the hospital in terms of opportunities for advancement, I again, looked for a new position and I ended up going to the University of Rochester Medical Center, where I got a job as a research technician in the Departments of Pharmacology and Physiology. And one of the benefits of that position was not necessarily the salary or those benefits, but I had the opportunity to go to school for free on a part-time basis. And so every semester I could take two courses at the university, which was adjacent to the medical center and I began my college career there. Tell me, we’ll jump just a bit ahead.

Tell me about you’re in college now, but tell me about now how your whole schooling, we’ll get back to the other stuff, but how your you graduated from, and then you went to, and you went to where, what is your schooling?

Well, my schooling, you have to understand that I was, at that time married with two young daughters, had a full-time job, full-time responsibility as a husband and father, was essentially doing school in the spare time. And I was doing it part-time. I was, when I left the university medical center to seek my career in the zoo kingdom, I was about four courses short of my bachelor’s degree, and I didn’t finish my bachelor’s until we made the move from Rochester.

Finished it where?

I had the choice of either being a graduate of, interestingly enough, DePaul University or the University of Rochester. And at the time I picked Rochester because Rochester was more prestigious.

And you got your bachelor’s degree from Rochester?

I got my bachelor’s degree from Rochester. And then your master’s degree from. Northeastern Illinois University some years later, and after that, a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

And it sounds like you’ve had this background in the medical community, how did this thinking about some other avenues, when did that start to come to fruition for you?

I think when I was at the University of Rochester, I thought about what other employment opportunities there might be, related to animals and animal work. When I was at the university and in the Department of Pharmacology and Physiology, we conducted a number of experiments, drug-related experiments on small mammals. And again, picked my interest, and I thought, you know, if I ever was gonna, if I ever was going to make the move to a different profession or to an allied profession, I could take all of this experience from the general hospital, all of this experience from the university medical center and apply it to an area that I was familiar with, and that was animals and the animal care. So I began to explore what the possibilities were for employment in a zoo, and it didn’t have to be within a regional area. It could be almost anywhere in the United States because we were as a family, willing to make the move and to leave friends and family behind. And what was, you talked about, you were doing research.

What was the research and did you write papers on it?

Were you encouraged to be a published person or how did that work?

The research that we did at the university was all related to drugs that impact the human brain. And we were doing drug testing in small mammals, in some small monkeys, in white rats, in mice and in cats to see what the effects of these drugs were. And these drugs were, at the time, largely drugs that we would characterize today as hallucinogenic. They were synthetic derivatives of morphine-like drugs and of derivatives that are extracted from marijuana.

Where were you responsible for taking care of the animals in this study or was that somebody else?

I was responsible for doing the actual experimental work on a day-to-day basis and doing measurements, making recordings and accumulating the data.

So you’re, what would you say was your first time actually working or taking care of animals?

Was that the zoo or was it previous to that?

I think the first time, the first opportunity I had, taking care of animals per se, was, were animals that I kept, were animals that I, myself, either bought and maintained as pets or for a brief period of time bought and provided supplies to some pet stores.

So at this time that you’re working at the hospital, you’re raising animals at home?

Yes, that I was raising animals at home, at the same time, I was working at the hospital and going to school.

Reptiles, mammals?

Reptiles, small mammals, no birds.

What kind of small mammals?

Pados, hamsters, dwarf hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, almost anything that one could reproduce in a small area, small amount of space. And then you were, selling them. Selling the babies as an added source of income.

Where did you get these animals?

Oh, in 1960s, it was easy to get anything from anywhere. If you had the money, you could literally order animals of all kinds from major ports of entry in the United States. My preferred sources were in Miami, but there were animals that came from New York City, from Long Island and from the West Coast, primarily from Los Angeles. And you purchased animals from these sources, these unique animals. I purchased animals, exotic animals, people would call them, wild animals from these sources. And in those days, almost anything. I mean, literally almost anything small could come through the United States postal service. So a box would show up at the house and the box would have a dozen small turtles in it, or the box would have a pillowcase in it with half a dozen snakes or a small box would come that would be labeled tropical fish.

And it would have small mammals in it, because it was during an era when nobody paid attention to any of those things.

Your wife was happy with this?

Well, I have to tell you that my wife, Gail, is somewhat short of a saint because during her childhood, in the home that she was raised in, she never even had a goldfish. So there was a significant period of not adjustment, but a learning, and she was very much encouraging, in terms of keeping animals in the house. At one point while I was still at University of Rochester, we had a rental apartment in Pittsford, New York. And the rental apartment had built into the dining room, the full length of the dining room, essentially a natural habitat. And that natural habitat was half aquatic and half terrestrial. And in it, and at that point I had some really strong interest in crocodilians. There were six species of young crocodilians and they’re ranging from dwarf caiman to American alligators.

And as this is ongoing, you’re thinking about, was it a driving passion that I think I now wanna work at a zoo?

Or was it just another place you felt you could use your talent to earn money and enjoy the job?

When we had that family converse, when we had a family conversation about, okay, what’s next?

What do we do?

I had done just about everything that I could possibly do at the university in terms of procedures and learning and perfecting surgical techniques and learning how to take care of animals. And I knew that I was being directed or driven to use the skills that I had in an animal-related job. And the first thing that I thought of, we thought of it was okay, let’s if, if that’s what it’s gonna take, let’s find a job in a zoo. But the Academia didn’t call you at that time to be- Academia didn’t call me at the time. I made some very good friends and in fact, they’re still dear friends during that time that were, that were my either advisors or professors who encouraged me to do, to look further into the animal world about no Academics was not even an option, because I had just struggled through my bachelor’s degree. What was your next move once you had made this decision how did that kind of come about. Well, beginning in about 1965, I wrote a series of letters to every major zoo or aquarium institution or wildlife center or wildlife park that I could think of, looking for an available position. And I didn’t care what it was, I wanted to work at a zoo and it didn’t necessarily have to be a staff position.

I was looking for any kind of starter position to essentially get my foot in the door, get my feet wet and to see whether this was something that I wanted to do. And we were really more than willing to walk away from family, walk away from friends, walk away from where we were very comfortable, in terms of the community, with the thought that if it didn’t work out, I mean, if we went somewhere and it didn’t work out, that we could always turn tail and come back and go back to places that we knew and family and friends that we loved.

Write the letters, what happens?

I wrote all of these letters. 1965, I wrote all, this is 1965, and I wrote all of these letters and there must have been, oh, easily more than two dozen letters directed specifically at that time, to either the director or the curator, whoever it might be, providing, you know, this is who I am. This is what my experience is, this is what my goals and objectives are. These are the kinds of animals that I maintained. I’m really interested in a zoological position. And out of all of those letters, I got two responses and they’re really very funny responses, looking back at it in hindsight. The one from Brookfield Zoo here in Chicago, came from Ray Pawley who was then a curator of reptiles, but he also was apparently the personnel manager for the animal department who very nicely wrote and said, “Thank you for your inquiry. We’d be happy to entertain your application, for a position if you had some zoo experience.

When you get some zoo experience, please write us back and we’ll see if we have any available positions.” And I was left with this quandary.

Okay, how do you get a zoo position?

How do you get zoo experience, if you can’t get hired by a zoo in any position. And then the second one came from Milwaukee County Zoo and it came from the then director, George Spydell, who wrote this very nice, and I still have it, handwritten note that said, “Don’t give up, a lot of my colleagues will not even bother to answer your inquiry, shame on them, keep going, there’s a place out there for you. You just have to be persistent and determined.” That made me feel really good and was what I needed to keep up this search for a position. So you continued to write letters. You had this job you’re- I continued to write letters. I continued to explore things. I took it upon myself to go to the mid-year meeting of the then AZZPA, which was in Buffalo, New York. I went to that meeting.

I was encouraged to go to that meeting by my local zoo colleagues at Seneca Park Zoo. I went, I met the then director, Clayton Freight, who just sort of took me under his wing. And he said, I’ll talk you around. You know, I’ll talk to you around. We’ll see what we can find for you. Yes, you should have a job in a zoo. I’d give you one, but we don’t have one. And I got introduced to the then director at Cleveland, who was Dr. Len Goss, a veterinarian, who interviewed me on the spot during the conference and said, “Okay, I want you, I want you to come work for me at the Cleveland Zoo.” I have to go home after the conference, I gotta do a few things.

We gotta get some paperwork cleared up. He says, “But I think we have a position for you. I don’t wanna make any promises other than be patient with me, and we’ll get this taken care of.” I said, “Okay, great,” I came home from that conference and I was jumping out of my shoes literally. And then about four days later, Clayton calls from Buffalo and says, “Lester Fisher in Chicago has a position open for a zoologist, are you interested?” I said, “Well, yeah, but I’ve got this thing going with Len Goss.” And he said, “Well, what you, there’s nothing better than having two positions at the same time.” He says, “Why don’t you follow up with that?” So I call Les, talk to Les on the phone, Les didn’t know me from a hole in the wall. I didn’t know him. And I flew out to Chicago, my expense, which is really funny and interviewed with the famous Dr. Fisher. And he offered me a zoologist position. And I think at the time there were two vacancies and said, “It’s your job.

The only promise that you have to make to me is that you will finish your college education,” because that was during the period when I was four courses short. So I assured him of that, went home, said, we’ve got a job. We all agreed that it was the right thing to do. And in the snow storm of 1967, we moved lock, stock and barrel from an apartment in Pittsburgh, New York to Rogers Park, to a garden apartment, which we all know in Chicago was a basement and began our zoo adventure.

What happened to Dr. Goss?

Dr. Goss followed up and called several weeks later and said, “I’d really like you to come out here.” We had made the move to Chicago and he said, “Oh, I’m so sorry, it took me so long, but it just took this long. Good for Les, you’ll enjoy working for him. I’m sorry, we’re going to lose you.” And we still remained good friends. So you come to Lincoln Park Zoo in 19- 67.

As, what was your title, what did they hire you as?

My title in 1967 was zoologist. My office was in the West end of the Lion House. I was issued four used uniforms. And I was told what my schedule was, which was essentially work three out of four weekends, and have as your days off, when you don’t have weekends off, work every Tuesday, you have Tuesday and Wednesdays off. And this zoologist position, can you give me a kind of, what was the hierarchy of the zoo when you then started, you were one zoologist out of whatever, there was a Lester Fisher director. Les Fisher was director. Jean Harts was assistant director. There was a general curator called George Irving.

There was a zoologist in charge of reptiles, and that was Eddie (indistinct). There was a zoologist in charge of birds, and that was Jim Mizaur. So that left me with the zoologist in charge of mammals or whatever else needed to be done. So your direct boss was the general curator.

Yes, that my direct boss was the general curator who was a, how should I put this?

A gentleman nearing retirement who always had done things his own way, and you were expected to do things the same way.

Did you have specific responsibilities given you, or was just you’re in charge of the mammals, period?

All mammals?

My responsibilities essentially, were learn the mammal collection, help where help is needed supervise on a day-to-day basis the entire mammal collection, focus on the children’s zoo and the nursery, because that area needed almost constant attention because of the number of infant animals that were being hand-raised in the zoo nursery.

What kind of zoo did you find?

You’d had experience of going to Rochester Zoo, but what kind of zoo did you find at Lincoln Park when you started?

The zoo at Lincoln Park, when I started was largely a reflection of WPA days, some leftover conservation core work, the collection was a very good collection. There were animals there that I had never seen before. I had a lot of book learning, but I didn’t have a lot of firsthand experience with some of the animals. There was general resistance to my presence by the senior, by some of the senior keepers and some of the animal caregiving staff, because I was characterized as the college kid who was coming to Lincoln Park to show them how to do things.

What form did that resistance?

What was that form of resistance?

Yeah, the resistance was sometimes it was subtle. Sometimes it was overt. Sometimes it was direct in your face. Sometimes it wasn’t doing things that should have been done just to see what kind of arise they could get out of me. The senior keeper in charge of the zoo nursery, Dick Reichert, was by all accounts, by anybody’s account, was an honoree so-and-so, but deep down inside, he was this gentle, caring, concerned person, you just had to get through the veneer. And one of the things that I learned was that I just didn’t push things, I didn’t enforce anything. I tried to learn from the considerable experience that was there and then change things for what I thought was the better as time and circumstances allowed. And that seemed to be an effective strategy with some of these old timers who had been doing it, some of them for 20 years or longer.

That strategy kind of developed, or you kind of had that as you were going in?

The strategy developed because I learned, after I ran into the wall two or three times, that the only thing I was gonna do accomplish was to bruise myself. And so I worked with what I had. You have to remember that during this era, a significant number of the employees at the zoo were, or what would be characterized by almost anybody as political hacks. They had their jobs because they were politically connected. They had their jobs because they worked for the organization. Some of them were alcoholics, some of them were derelicts. Some of them were deviants, a significant number of them, when their paychecks came and they had the sign George’s check sheet that they received their check, signed an X because they couldn’t write their own name. Some of them couldn’t, I learned, if you just assume that everybody can do what you can do, that you can read and write, some of them couldn’t even read and write.

So to try to implement any kind of written guidelines or instructions for whole areas of the zoo, whether it would be bird, mammal or reptile, just wasn’t gonna work because they couldn’t read, or they were incapable of understanding what was going on.

You talked about your management style then, what was the director’s management style and what was your immediate boss’s style?

Did they conflict?

Were they in sync with what you were trying to do?

Les Fisher’s management style was pretty much what Les Fisher’s life has always been, easygoing, friendly, outgoing, everybody’s buddy, don’t make waves under any circumstances, do whatever needs to be done, but do it in a politically correct way. His number two, Jean Harts, was essentially in charge of the zoo and the personnel and the collection. He was the person who acquired animals. He was the person who sold or traded or declared animals surplus. He was essentially the man in charge of the interior of the zoo, while Les was right up until the very end, the external force of the zoo. He was the person that, he was the person that everybody thought about when they thought about Lincoln Park Zoo after Merlin Perkins. Were there any major issues or things that you saw that the zoo was facing when you first came there as well, as just, or as you moved through your responsibilities as well I guess. I think the only evolution that took place from a personnel standpoint, was that we made a conscious effort.

I mean, we made a conscious effort that people would be cross-trained, that they would know more than how to take care of antelope for instance, or how to take care of the chickens or how to take care of the handleable animals in the children’s zoo. There was a conscious effort to begin to cross train people, so that on days when people weren’t there, or on days when people were sick, that you had the logical people to put into those slots.

Did you find that the zoo had good record keeping?

A good question about record keeping, the record keeping was essentially non-existent when I arrived at the zoo and one of my first responsibilities was develop an inventory system. There were lots of ledgers in buildings that had either daily notes or scribbles on a page, in a bound volume that went back many, many years. That essentially was the inventory record that the zoo kept. There was no formal carved file, except for some very old and geriatric animals that had been there almost from the beginning of the modern Lincoln Park.

Was this something they directed you to do, or this was on your own?

Now, this was one of my, this was one of the things that I were supposed to accomplish over the course of time, no rush, no hurry, do it with detail, get as much information as you can from the old records as new animals come in, include that information. And each animal in the zoo had, at that time, essentially a four by six or a little smaller, I think it was probably a four by five inventory card that had all of the available information that we knew about that animal, common name, scientific name, its sex, where it came from, whether it’s kept, or born, or wild-caught and any incidental notes about it. And those were kept in individual card files in the various areas, in the bird house, in the small mammal house, in the reptile house. And I kept a master copy, master file in my office. So that at any one time I knew exactly what was in the zoo collection and where it came from and what its history was.

As zoologist, did you, or were you required, or did you desire to make daily rounds of your kingdom?

I couldn’t be kept out of the animal areas much to the chagrin of some of the old time keepers. I made a point of being not only around, but in every area, front, back, up, down, if there was a closet, if there was a basement area, if there was an off-exhibit area, if there were holding stalls, if there was a storage area, I wanted to know where it was, what was in it, who had access to it. And I wanted most of all, to have a key to it, so that I could go any time that I wanted to go.

How important would you say these rounds were to you or to people who aspire to be in a profession?

I think these rounds were very important to me. I learned a great deal by just being in the animal areas with the animals and with people who took care of the animals. It was an essential part of my day I, before I did anything else on any given day, I was out on the zoo grounds looking at the animals, talking to the people who were caring for them. And I think that was important. It was important to me from a learning standpoint, but it also was important to them in terms of our developing a relationship and developing in trust in one another. And gradually some of the barriers broke down and some of the old timers would teach me their little tricks. If you ever have to move this animal, this is how you do it. If you ever have to get in there and grab this animal, this is how I would do it.

This is, these are the nets that we use. These are the tools that we use. This is a quirk of this particular ostrich, or this is a quirk of this red kangaroo. And so I got to know some of the animals in the collection as individuals. Give me one individual that stood out. One individual that stood out. One individual stood out. Well, I had never experienced a great ape before.

I mean, I had seen great apes, I had seen chimps, I’d seen harangues, I had seen gorillas. One day when I was in the old primate house, the then senior keeper, Roy Hoff said, “Come here, kid, you wanna meet an orangutan?” And so I went behind the scenes with Roy and Roy did what he did to me, after hindsight gives you a 2020 vision. He did what he did to every newcomer. And that was he simply unlocked the cage door and out flew this full grown female orangutan, who literally, and as you know, it’s like being suction-cupped, they simply grasp onto you. And there’s no way to get them off until, or unless they’re ready to leave. And he got the biggest chuckle, first of all, of my reaction to having an orangutan, making kissy faces to me and hanging on to me, as he walked down the service area and locked the door and left me there sitting with the orangutan. Sort of, okay, you wanna be a zoologist in this zoo, you wanna know about orangutans, here you go, buddy. You indicated there were others who zoologists, who had other responsibilities.

What was your read, did they all have the same, did you all have the same responsibilities in your different areas?

Did they all have the record keeping, et cetera?

And what was your relationship with these zoologists?

I think my relationship was really good. Eddie (indistinct), who was the zoologist in charge of reptiles and the reptile house later to become curator. He really was my mentor. Eddie kind of took me under his wing. In fact, in the beginning, we lived in the same apartment house. He at one end, up top and we at the other end, down in the basement. And so we got to be good friends. It also was clear to him that I knew a lot about reptiles and that we could share.

We could share that information. We could share that excitement with each other. And I also knew that if I was ever gonna make a mark in the zoo, that it had to be with mammals, Eddie was par excellence in terms of his ability, his intuitive knowledge with reptiles and the guy who was in the, Jim, who was in the bird house, he wasn’t going anywhere, he had that under control. And I really didn’t develop an interest in birds until somewhat later in my career. And so it left me with mammals and Eddie provided the tutorage that I needed, in terms of the subtleties of the political life of the zoo. He helped you then went your way through the, I’ll call it as you did the politics of the zoo. Eddie definitely helped me understand the politics of the zoo, understand some of the quirks of the personalities involved in the zoo and tried to keep me on the straight and narrow. You said there was a senior general curator when you started.

You’re the college kid.

Did you bump heads in philosophies?

Did or was he happy to have you there and a new era was being issued or did he expect you to fall in step with the rest of his zoologists?

The then general curator, George Irving, was an interesting guy. You have to understand that this was my first job. I was literally beside myself with joy that I had this position. I went to work a week before I should have, and he made it perfectly clear to me that I couldn’t begin employment at the zoo, despite what the park district had said, because it was midway through a pay period and he didn’t keep the books that way. And I said, “I’m here, they told me to start, I’m starting, I’m ready to go to work.” He said, “All that’s fine, but I will not put you on the payroll until the next pay period. And if you’re here, you won’t be paid for working for this week.” I said, “Great, I’m in, I don’t care about the paycheck.” And I went to work, that was our first interaction.

And did he essentially, or you know, it sounds like you had a lot of freedom, but did he give you the freedom?

Did the upper management essentially give you some general guidelines and then go do what you wanna do?

Did you have a lot of freedom?

I had an exceptional amount of freedom. I mean, any errors that I made were mine to make, I was essentially given a free hand with everything, from record keeping, to diets, to the management of a collection, to a more limited extent to who worked where and when, which was George’s realm. And I just dove into it. I mean, completely dove into it as an example of the degree of freedom my first weekend earned. There was a camel born, a dromedary, it was the first dromedary to be born at the zoo in a long time. The senior staff member on call, there was always one on the grounds, and one on call and the senior staff member on call was Jean Harts, his assistant director. And so the camel’s born, I looked at the mother and I said, she’s got mastitis. I know she’s got mastitis, I’ve seen mastitis before, the baby was trying to nurse, the mother was kicking the baby.

It was a Sunday afternoon. The zoo was full of patrons, something needed to be done. And my first inclination was I have to get that baby camel out of there. If the mother has mastitis, she’s never gonna let the baby nurse. And so I talked to the keepers in the area and they said, “Oh, you aren’t going to, you don’t wanna do that. But then we’ll have to hand raise her.” And I said, “Well, that’s no big deal. We’ll move her over to the children’s zoo. Or you can hand raise her here adjacent to her mother.” “Oh no, we can’t do that.

That’s not part of our job description.” I said fine, I said, “But I think we ought to take her.” And they said, “Well, you can’t do that without calling the assistant director.” I said, “Okay, I can do that, but we’re gonna take it. So get ready guys.” So I called Jean at home, got him. And he said to me, and I told him my story. And he said, “Here’s some advice for you, kid, don’t ever call me again when I’m on call on the weekend, do what you want to do.” So I get off the phone and said, I guess I can do what I wanna do. So the boys and I, I said, “Okay, you would distract the mother, and well, I’ll grab the baby.” And we went in the outdoor pen in the old antelope zebra area and grabbed the baby and pulled it inside. And then I didn’t know anything about raising a baby camel got a Coke bottle, got it to a lamb’s nipple, got some canned milk and water made an appropriate dilution. The baby began to nurse, all was well with the world. And then the second thing happened, somebody called the press.

And one of the old time sometimes, or tribune photographers showed up and said, we want a picture of you and the camel. And so I fed the camel and they took a picture and it showed up on the front page or the back page or whatever page of the newspaper the next morning. And then I got my second introduction to the politics. And that was, that morning I called into the director’s office and the director said, “You know, public relations is the responsibility of the director and I’m the director. So you will,” essentially what he was saying is, you will, if you value your life, you will never ever do that again, with or without anybody’s permission. And I tried to explain to the best of my young abilities, that it wasn’t my fault, that I had no control over it, that it had just happened. And he said, “All that aside, you understand?” I said, “Yes, I understand.” And then the assistant director, as I was coming out, pointed his finger at me and said, “You remember our conversation of the weekend.” I said, “Completely fully you and I are on the same plane. I understand exactly what I should do.” And that after that, it was get out of my way, because I knew I couldn’t do any wrong.

Now, at some point you said, reptile and trust, you’re gonna be the mammal guy. You developed this interest in edentates.

And how did that get started?

Was this as you were a zoologist in that position, and why?

I think a couple of things, a couple of things occurred during my career that were purely opportunistic. One of them was I wanted to go South America. I had read all of the early natural historians. I had read Bates. I was aware of the work of Beebe at the New York Zoological Society. And I knew I had to go to the tropics because I had to understand for myself, I had to feel whether it was a place where I wanted to spend some time or it was a place that I was terrified of. So in 1972, by then I had graduated from the University of Rochester. It was instilled in my position probably about then I was being called curator.

And I think it came with a little more money. I applied to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia for a grant to undertake a trip to south America, to look at small mammals, but particularly those small mammals that are generally referred to as edentates or xenarthrans or the armadillos and the sloths and the ant-eaters. And I had an interest in them because they were essentially animals that nobody loved, nobody cared about. They were animals that were interesting to me because of their natural history, their lifestyle, their feeding habits, they were animals that were not generally seen in zoos. Lincoln Park had a wonderful small mammal collection. And I thought, these animals really ought to be here. This is something that we could do, but I need to learn something more about them. So the American Philosophical Society founded by Ben Franklin, saw fit to find enough funds with a little bit of family money as well, to send Gail and I to Argentina first, and then to Paraguay second, and to spend a month away from the zoo, two and a half weeks in Argentina, and a week and a half in Paraguay.

Gail was with me the whole time in Argentina and part of the time in Paraguay, because we had two small children that were needed to be taken care of by a family member during our absence. And I really, I really fell in love with the land, the people, the environment, and the animals that were there and made some very good friends, some who were just interested people who happen to have a way to get to places where there were animals. And one was a commercial animal dealer who was largely a bird exporter out of Paraguay. And that was the start of my infatuation with South America. It was also the first time that I caught, except for North American animals, it was the first time that I’d ever captured animals in the wild that I actually went like Frank Brooke, bring him back alive, to find where the animals lived, to see them in nature and to be able to capture them, acclimate them for later shipment back to the zoo and to learn as much as I could from them. We’ll talk a little more about that in a second, but I wanted to go back to zoologist to curator.

Was this a title change?

Was there another zoologist coming up and you became, there was a new position created for you. Did that affect all the zoologists or part of them. Zoologist to curator occurred for all of us simultaneously. It occurred because there was a pressure, Les primarily, Jean to a lesser extent and via Jean and Les to the park district to get us some more funding and benefits. Keepers got an annual raise. It was largely related to the current economy. The zoologist positions pretty much stayed the same. If we got anything, it was a little bit, it was less than what the keepers got in terms of percentages.

We all simultaneously put pressure on Les to do something for us. Remarkably, Les always got raises, but his staff didn’t and it got to a point where he realized that he needed to do something. And I think what they decided downtown was, in order to give us additional funds, they had to change the titles. And so the job descriptions, as one knows, within the park district had to be rewritten, which took forever. When the jobs descriptions were rewritten, regardless of what your job was, we moved from zoologists to curators and there became formal, essentially, curator mammals, curator reptiles, curator birds, largely a reflection of the areas that we each and all were responsible for. So your responsibilities essentially were the same. It was a title change. It was a title change.

It was a title change and a title change necessitated by the need for additional salary. And the salary could only come if there was a new job title. So now you’re the curator of mammals and you are interested in edentates, you’ve been to South America.

Did you have a goal plan that you wanted to do with this, this group of animals and were you free to do whatever you wanted?

I didn’t, I don’t, I think in the beginning with regard to the edentates, I didn’t have a plan. I had a loose plan, the loose plan would have been, I’ve got to understand these animals. The way to understand them is either look at them in nature or the way to understand them is to bring them into captivity and to study them in captivity. I think it all began that way. It was reinforced by the trip to South America and the subsequent shipment back from South America of a range of animals as a consequence of that trip, that had never been done. Two things had never been done by a staff member at Lincoln Park Zoo before, a staff member had never had researcher travel funds. A staff member had never caught animals in the wild and acclimated them for shipment back to the zoo. And as a consequence of that South American trip, a number of armadillos of a couple of species, at least three species came from Argentina and also from Paraguay.

And a number of other animals came to the zoo, that the zoo had a potential interest in, both in terms of birds and reptiles, largely out of Paraguay. For instance, the importation of green anacondas that occurred at Lincoln Park in that 72 through 74 period of time were animals that I captured along with other people in Paraguay. And it was the first time they had been exported into the United States. They had been in Europe before, but they’d never been in the United States. So they came to Lincoln Park, they came to Eddie. Eddie was thrilled to have these yellow anacondas. Additionally, birds came to the bird collection, Bellbirds came, seriemas came. It was just after the United States had put on a bird ban on citizen birds, on parent-like birds, but there were other, there were other birds that were available.

And so when the shipment, when the consignment arrived in Chicago, it included all three major groups of animals, a significant number of animals, all of which had been acclimated prior to shipping, they had been hand acclimated part of my responsibilities in Paraguay while I was there at the compound, was taking care of the animals every day, and making sure they ate, making sure they were well taken care of. And out of there came, out of that Paraguay shipment came the first tamandua, came the first giant anteater for me, came some of the first primates and they were all very well-received, both in terms of health and circumstances when they arrived at Lincoln Park Zoo. And the zoo was very supportive of those efforts because they knew what they were getting as opposed to getting animals from an animal dealer. I got no compensation for any of those animals. The zoo paid the paid the collectors or the animal dealers directly for whatever was exported. So what do you feel, you’re looking back, your contribution to this group of animals in the research or the husbandry you did has been. Oh, I hope, I think with regard to edentates, particularly in South American small mammals, I think I opened the door. I opened the door for other people to be interested in these very unique, very, in many respects, bizarre animals that hadn’t been well exhibited or only exhibited occasionally and hadn’t lived very long.

I think my contribution was that I did several things. I introduced the zoo world to animals they already knew, but hadn’t done much with, I worked on their nutrition, on their behavior and on their reproduction. And I had a lot of help along the way from the veterinary staff, the keeper staff, and from colleagues in other zoos. During that time, you had a philosophy, I believe, of, you published during this time about these animals.

What was your general philosophy about the sharing of knowledge?

It’s an interesting question about the sharing of knowledge. During my first job, my first job at the Rochester General Hospital, the pathologist, Milton Borod, believed very strongly in, that if you study something, if you find results that you should publish. He also believes in a kind of a second law. And the second law was you give credit to people who have helped you along the way and with the work. And so when I went from the general hospital to the university medical center, my boss there, Dr. Jean Boyd, he was of the same philosophy. If you work on a project, you get credit for the project. And so, publications were shared publications. And so when I got to the zoo and began, I began to understand about these animals and their needs and their nutrition, I thought it was important to share that knowledge much as I had been taught by those two previous employers.

And that’s been my general philosophy, I’ve added a kind of an additional thought, and that is that you should publish where it’s going to do the most good. Many people publish in journals that will in peer review journals that will give them prestige because they published in this journal or that journal. My philosophy was I didn’t really care as long as it was peer reviewed, I didn’t care what the journal was, what the publication was, as long as it would hit the audience. So if you look at my CV, you’ll see that my published works are in some very strange places or so it seems, unless you understand what that philosophy is. During that time, during the time that I began to publish and others on the staff began to publish at Lincoln Park, I think International Zoo Book, Zoo Yearbook was the annual Bible of zoo information. If you needed to know anything about animals in your care or about exhibits or about nutrition or about veterinary medicine, that was the place to go. And that was the place to publish. And fortunately, they were very gracious in their acceptance of articles for publication, both from me and from other members of the staff, as well as from others in the zoo world.

Knowing that you’ve done this work with edentates do you think there needs to be more work done on the edentate group in zoos now, or has it all been done?

I think the one of the, one of the sadnesses of my life in terms of reflection is that the significant edentate collection that was at Lincoln Park, when we made the decision to divest ourselves of that collection, to disperse it to other zoos, for one reason or another. I look back on that as that was a very hard time for me, I understood the need to do that. I trusted that others within the profession would take that, take those animals and take those groups of animals and would carry on the legacy that had been started at Lincoln Park, not just mine, but all of their caregivers staff, as well as other staff members at the zoo. But sadly, it only worked for a short period of time. And those animals are very uncommon, very rare, very unusual in zoos today, largely because the animals aren’t available. And because there isn’t the interest in them from the professional staff that there was during my time at Lincoln Park. And that’s sad because they’re very interesting. They have all kinds of, if you need to put a use to an animal, you can use them in education programs.

You can use them in interpretive programs, you can use them in all kinds of conservation efforts and regrettably tragically, it comes at a time when the animals simply are not available from nature, because there are no more, or essentially are no more commercial animal dealers, but there’s a series of regulations and regulatory agencies that don’t encourage you to do importations. And there are very few people in the profession today who would do what we did and that is go to nature, find the animals, spend the time acclimating them, import them into the United States into your collection and to others. That’s a tragedy. You talked about this grouping of edentates and your freedom as a zoologist or a curator. And you had kind of picked out a space within the zoo to hold this collection that you were working on. Was there kind of tell us how that, I got permission to do it. And also was there a pushback from the senior management or did they just, again, let you go and do what you want. It’s an interesting question about housing and off-exhibit housing and how do you develop it and how do you gain the space.

It became very clear to me, that we needed to have significant numbers of animals in order to do reproduction, that we needed significant number of animals to know something about their behavior, their activity cycle, their nutrition. I look for an off-display area. The lion house was perfect. It essentially was a storage space for animal crates, probably 50 years worth of animal crates. It was perfect in terms of an environment because it was warm, they were tropical animals. It was well lit, it was off-exhibit. It was little traveled, it lent itself to that. And so it began very slowly, you know, a pen here, a cage there, a walking exhibit here, and the park district construction people were very cooperative.

And essentially I was given free rein, I was on one hand, not discouraged. Let’s just see how this plays out.

And it also interacted with a pathologist that we had on staff who had an interest in, what are the pathology, what are the disease processes related to these animals?

What happens when these animals die?

What can we learn from them?

And so it was kind of a one, two effort on our half, on our behalf to convince the director Les Fisher, that this is something that the zoo needed to do, and we were willing to do it. And as a consequence of that, she and I wrote a grant proposal for funding to study the diseases of this group of animals and was going to submit it to the National Institutes of Health or to the National Science Foundation, and Les decided that he ought to send it to his colleagues in Washington at the national zoo first to get that, get an overview of it. And strangely enough, about three months later, the national zoo and its research scientist, John Eisenberg, recruited two PhD students to go to South America to study this very group of animals that we had proposed this work for. You were kind of groundbreaking there. We were pioneering. A philosophical question. You had this freedom. Do you see today, as you understand the profession, that the curatorial staff does not have, or do they have that freedom to pursue their personal Academic interests, or are they, do they not have that freedom.

To talk about the curatorial staff then, and the curatorial staff now, and degrees of freedom or the ability to shape one’s own future it’s the difference, it’s 180 degrees from where it was during the time that I was at Lincoln Park. I think our philosophy, what the curatorial philosophy was better to ask forgiveness than permission. Just if you think it’s the right thing to do, then you go ahead and do it. And then you take the repercussions, if there are any. We made very few mistakes and everybody on the zoo staff from top to bottom looked good for some of the work that was being done. And so the director and the assistant director, and the general curator were all part of taking credit for the significant advancements at the zoo, which was a wonderful thing. I think if I had to compare that to today, I think the curatorial staff, even though they’re probably better educated in terms of, it’s very unusual in major institutions for a curator not to be a master of science or not to be a PhD or not to be a DVM PhD or not to be a primatologist or not to be an ecologist. But they’re lacking something that we had.

And that lacking is they appear to be, at least to me, afraid to make decisions, afraid to make decisions in the sense of, oh I have to check, I have to see if we could do that. I can’t make that commitment. I can’t give you an answer to that now. Part of that is because they simply don’t have the street smarts in terms of zoos and zoo animal care that we had during our days at Lincoln Park, they don’t have the street smarts and there are impediments to making independent decisions because there’s a whole hierarchy now of, I wanna say regulatory or legislative for internal committee discussions that have to take place before anyone would commit themselves.

Why don’t they have the street smarts?

They don’t have the street smarts because they don’t have the experience. They don’t have the experience because they’re unwilling to take a chance. They’re unwilling to take a chance because there are repercussions. They’re unwilling to take a chance because there’s this structure in place, which is an impediment to essentially learning on a day-to-day basis. You indicated that when you became curator, your responsibilities didn’t significantly change, but yet at that time, the zoo was undergoing major remodeling/renovation.

What part did you as a curator have in that?

As part of the growth of the zoo, part of the growth of the zoo and part of the restoration of the zoo, it undertook several capital campaigns. All of the staff were involved in both public relations, as well as the design elements of those campaigns.

And so additional responsibilities, including participating in planning meetings for facilities, providing direct things like how big does this area need to be?

How warm does it need to be?

How much space does it need to be?

What kind of safety features are there?

What kind of feeding elements do we need to build into it?

What kind of considerations are special for this group of animals, those sorts of things. And that was just the start of several, now to this day, probably a hundred million dollars worth of restorations, renovations that took place at Lincoln Park Zoo, and it fell to the curatorial staff. So if it was a mammal area, I had to be there. If it was a bird area, the bird curator had to be there. And if it was reptile area, the reptile curator.

Did that take you away from your other daily responsibilities or was it just added up?

I would say that it added on to responsibilities, but it added on in a very good way, because it gave the opportunity to share one’s knowledge and share the experience and to translate it from what was there now to what could be there in the future. There’s no question that it was a lot of additional work, but I think the satisfaction of seeing it to completion was in some way very nice compensation for the effort. At this point in time, the senior management did change. The assistant director did leave and a new assistant director, or the general curator left and new staff came in.

How did that happen?

And how did your relationship change or did it, now, you’re a little more experienced, you’re not the new guy. I think over time, we all know that institutions change both in terms of their hierarchy and in terms of what their needs are. People retire, people move along. People go to new positions. The same thing was true at Lincoln Park. I think internally the impact that it had on me, as well as the other curators was that we continued to grow. We continue to evolve. Our collection went from a essentially posted, stamp-type exhibits with animals that could be largely acquired from commercial dealers to more concern for interpretive programs, more concern for education, more concern for conservation.

The new staff brought experience with them, brought some of these ideas with them. And I think the zoo gradually evolved and had to evolve particularly with the capital improvements that were being made. We, our role changed significantly in that our emphasis went to conservation and went to education.

And these people that were coming in, they were bringing that philosophy, I mean, for example, when the senior curator, general curator left, did they replace that position?

Oh, when George Irving, the general curator retired, when George retired, that position became essentially a person to oversee the curators and the staff in the animal collection, it was no longer essentially a timekeeper position. It was a position that was in a sense required by the growth of development of the zoo and its philosophy. So they brought in a new genera curator. They did bring in a new general curator.

Your relationship with that individual, now that you’re the more experienced guy?

I had no difficulty with any changes that were made in the staffing. I saw that as an opportunity to share what I knew and to learn from them based on their experience at other institutions, and by and large, I think we were very compatible.

Did you find that in the position of curator now, that you had to do more managerial practices, were you more interested in that, were you losing your animal interaction or did it essentially, again, stay the same?

The growth from zoologist to curator, and then the addition of professional staff caused, or me in particular, and I think the rest of the curators to take a step away from what we like to do best, because we had to become managers. We had to become, essentially, people concerned about personnel. We had to be concerned about scheduling. We had to be concerned about legislation. We had to be concerned about all of those intricacies. And so with every step and every positions you take from, as you move up the ladder, so to speak, you step away from the things that you like the most. And so that change, particularly with the addition of professional staff, it was, yeah, it was a step away. There’s no two ways about it from what was the true pleasure or the true joy of every day at the zoo, but it was a necessary change.

It was all part of logical growth.

And still you were making daily rounds?

Still making daily rounds or a lot more meetings, or a lot more interactions. The zoo society was coming into its own. As a friend of the zoo, as a supporter of the zoo required more public relations, more special presentations, more donor tours, which all took time away from the day-to-day management of the collection. But on the other hand, it was absolutely essential for us to do in order to grow.

At that time as curator were you or just senior staff involved in the budgeting and policy making at the zoo?

During the time that the zoo was, during the time the zoo was under the park district’s management, the director was solely responsible for the budget. There were a bunch of codes in budget items.

Each of the curators would be asked for a major pieces of equipment or major expenditures, or to put forth what conference or meeting would you like to go to next year, how much would that cost?

There was a overall collection budget. And the largest part of that collection budget was, were the funds to purchase animals, for animal purchase and for animal transportation. And we all fed out of that, so to speak, pot, and that largely was determined by the director, but in concert or consult with assistant director.

Was there a commitment to professional growth?

You mentioned conferences, ’cause that costs money. There was, it was absolutely essential that the zoo grow professionally. It was doing that in terms of the staff it was taking on, it was doing that in terms of the capital improvements. The, so the staff needed to have interchanged, needed to have something more than conversations on falling with colleagues. And the way to do that was at the annual or the twice annual depending on the circumstances conferences where one could get together with our counterparts in other institutions, in (indistinct) relationships, and to reinforce the relationships were there. And that was very important because those relationships that occurred both on the telephone and even at those meetings, all were relationships that lasted a lifetime, they were gentleman’s agreements, they were handshakes. They were at a time when your word was your word, if you gave someone your word, that that was the way it was going to be, no matter what.

During this time did you have mentor or mentors outside of the zoo itself?

Was Dr. Fisher a mentor or other people outside the profession?

I think there were some significant mentors for me during this time. In tropical America, Dr. Nick Gale, was a very strong influence on my life. He was a DVM, PhD, doctor of public health, he was a civilian employee in the United States Army in the area of the former canal zone. Many trips were made to Panama while I was curator and general curator, largely because I was undertaking my master’s work. And my master’s topic was the two-toed sloth. And so I went to Panama to study sloths in the wild. All of the colleagues that I had met along the way, Clayton Freiheit, Danny McClowsky, Jim Dolan, Larry Kilmer. I mean too many people, too many people to name, all had influence on me and on my decisions and on my growth in the profession.

Was there anybody that when things got tough for you had a decision that you got on the phone and you kind of talk with them?

I think if I relied on anybody for insight in the animal world, it was probably Jim Dolan in San Diego. He was probably my go-to guy.

And then during this time, were you helping or were there new policies that were being, as the zoo’s growing, put forth at the Lincoln Park Zoo?

And what kind of say did you have as a curator in that?

Well, with the growth of professionalism, everything became the written word, the printed word. And so there had to be a collection policy. There had to be euthanasia policy. There had to be a formalization of the processes for record keepers, for a record keeper. They had to be all of these, essentially cookbook recipe type information sources that in the case of your absence or in the case of you no longer being there, that this information could be passed from person to person.

Was this something came from the top down to you to say, take care of it, or were you making recommendations to the higher ups to say, we need to get some of this stuff in?

Well, it came from the top down, but it came from the top down largely because there was pressure by the National Association of Zoos and Aquariums to formalize policies and procedures within zoos and aquariums and wildlife parks. And so the edict would come from AAZPA, now AZA, and then it would be passed from the senior staff down all the way down, oh that this is what we had to do, this is why we had to do it. And here were the guidelines that were provided. And when the assistant director left the zoo, a new assistant director came in from within the ranks.

Your relationship stayed the same?

I think so, I think my relationship didn’t, I don’t think there was any, there’s no, in my recollection, there’s no visible change in relationships with a change in hierarchy. Actually the departure of the assistant director and the hiring of a new person as a general curator/ assistant director was a welcome relief because it moved along some of the old and provided an opportunity for the new to get a foothold.

Were there situations that you can tell us about that you might’ve learned something new on the job that you did not know before?

Well- I learned from the first weekend that I was on with the camel, that you have to be very quick to grab a baby camel because adult camels can kick both rear legs off the ground at the same time, and you have to be away from them. I learned from an old timer, senior keeper, Joel Mcchale, that if you want to move an ostrich, the way to move an ostrich is to get an onion sack and two belts. And you put the onion sack over the ostrich’s head so that it doesn’t know where it’s going. And then you put one belt around his neck, on the right-hand side, and one belt around its neck on the left-hand side. And you stay away from it and you lead it anywhere you want it to go, and it will willingly go, just like driving a car because it can’t see, and it doesn’t know how to resist. That those were among my basic. And there were dozens more I can assure you, but those stand out in my mind. I also learned how you could appear to rake a yard so that it appeared to be clean, but you actually hadn’t cleaned the yard.

You had just raked it so that you looked like it was clean. There were all kinds of little tricks that I learned from my comrades. And you had indicated and said at one time that you felt you worked at Lincoln Park Zoo, move on word, but that you worked at Lincoln Park Zoo during a golden age.

Can you kind of tell me what you meant by that?

It was a golden age, at like in part, because we had the degree of freedom that we had. It was a golden age at Lincoln Park because there was, there essentially was no animal anywhere in the world that we couldn’t acquire if we could make the contacts. It was a golden age because the director of primarily, either allowed, probably allowed or didn’t really care what we did, as long as it all turned out in the end. It was a time without oversight. It was a time without committees. It was time without regulations. It was a time without the Endangered Species Act. It was a time when there were animal dealers, specialized animal dealers in the four corners of the world that you could count on, they were people that you knew, they were people that you could trust.

And again, I go back to the, your word is your bond. If they said they were going to do something for you, they did it for you. If they said I have this and it should go to you, and this is what his condition is, that’s, those were all, that was all a truism. We were very fortunate to live in that time. And a whole bunch of things happened during that time that could never, ever, ever happen again. When we moved from Rogers Park to Evanston, and our girls were growing up, Gail worked part time at an orthopedic surgeon’s office, but it was a time at Lincoln Park when we had outmoded and outdated facilities for great apes, primarily for chimps and for gorillas and the merit house in Evanston was an ancillary nursery for several years, for a handful of chimps, and more than a handful of gorillas that got there first six weeks or their first eight weeks, or a little more, being taken care of by just two of us, because my philosophy at the time was better to have one or two people taking care of an animal like that and getting to know the animal and its peculiarities, versus having a whole bunch of volunteers who were ready and available in a zoo nursery situation, to confound the insight into the animal’s behavior and into the animals’ needs. And so there are fond memories of all kinds of creatures being at the house during that time from new dad with a broken leg, to a black and white ruffed lemur who needed special care, single orangutan, several gorillas, as I said, and lots of chimpanzees. The assistant director at Lincoln Park Zoo left to become director of another zoo, opening that position.

Tell us about, you know, how that transpired and why did you decide to apply for the position and were you just the choice automatically, or were there other people within the zoo that wanted it or internationally that wanted it?

When the then assistant director went on to become director at another zoo, the position opened. And I don’t, as I look back on it, I really don’t know how it all happened. I don’t think I was the heir apparent. I think there were certainly would be interest from the outside. It was an enviable position because the zoo had some significant status and reputation then. There had been a lot of the staff that had gone on to become zoo alumni and had institutions of their own either in leadership or just under leadership positions. And I’m really unclear, I’m really unclear how it happened. I think in reflection, first of all, I’m very glad that it happened.

I’m glad I had the opportunity, but it did, as I alluded to earlier, it brought me one step further removed from the things that were most important to me, at least in the early part of my career. And I had to make that conscious decision about would this administrative position eliminate those possibilities that I had for the collection and for building the collection. And I think the answer to that is, yes, it did, but it was worth assuming the position, because then I could do things at a different level to improve zoo life, both at Lincoln Park and for its staff and all the way around, but also for the profession.

What were you thinking though, when you said I could improve?

So you had ideas or you had goals that you felt I can now further them and what were they?

Not so much stated goals or list of goals or something put on paper, but rather philosophical goals, attitudinal goals about how to treat the collection, how personnel would treat it, how people needed to be treated as individuals, how we could make the zoo a more inviting place to be, how to open it up to the community, to share the idea that the zoo was an island in the city. It was a refuge that anybody could come there literally at no charge whatsoever. And to enjoy stepping out of the city into this kind of island of vegetation and animal life, to lose themselves, to leave their worries and their troubles behind and to just enjoy the moment. So this wasn’t happening before, or it needed to be happening to a greater extent. In my opinion, it needed to happen to a greater extent. We needed to open ourselves as an institution, to the larger community, beyond what we were doing. And so we had a role to play primarily in education, but also we had a role to play in conservation, a role to make long-term commitments to both national, international programs in terms of animal management, in terms of the conservation of species. Were these conversations that you had with then Dr. Fisher, who was the director before you assumed the position.

Did he understand what you were going to want to try and do, or was he telling you what he needed for you to do in this new position?

I think when, I believe that when I interviewed for the position, he had a list of things that, he had a list of things for me, that for me, an individual, that he said, these are the things that I’d like us, which means you, to accomplish. And these are the things that we’re going to have to put aside in order to make those accomplishments. And so it was clear from the start that part of my day-to-day interaction with the collection was going to take second seat to the administrative responsibilities that he was giving me. And essentially the, essentially the assistant director was the director in the director’s absence and all of that and all that it entailed, which meant that it was a learning curve on my part to take on some things that I had only occasionally stepped into, public regulations, donors, soliciting donors, working with the zoo society to raise funds, in the director’s absence to give public speaking engagements, commitments to the community for a zoo, personal appearances, those sorts of things, which I had done some of, but there was a whole bunch more associated with that position. And it was during a time when the zoo was very visible, the zoo was trying to raise funds for additional capital campaign. The responsibilities were being shared across the board, and it was clear to me that that was something that I had to do as part of this position.

Was your relationship with Dr. Fisher the same?

That is, his management style continued to be what it was, was he, was there a different relation, kind of laugh.

So was there a different relationship because now you were in a new position, so it changed a bit or stayed the same?

I think our relationship, we always were good friends, we were colleagues. I took his daughters to Africa one year, we babysat for his house and his dog when they were away on trips, we had that kind of a relationship, but we were not truly friends in the typical way that one would characterize a relationship with another person. And it was almost as if, it was almost as if there was a line that I could not cross because, and I didn’t know what that line was, but I knew it was there, because that was his realm, that was his sphere of influence and activity. And that I shouldn’t dare go there because it would not be in my best interest. That became apparent during annual budget reviews and personnel discussions, financial decisions, particularly with interactions with the park district. And to the best of his ability, he tried to keep me out of those discussions so that he was the only one who actually knew what the details of things were. And I never quite understood that. There were times when he, there were times when I felt that he clearly believed that I was challenging him in one way or another, by what I had done or what I had not done.

And he would let me know in uncertain terms. And I think during my tenure as assistant director and then as the director of collections, he and I took probably two famous Lester walks.

And if Lester wanted to go for a walk with you, that it wasn’t good, but the Lester walk was, oh-oh, what do I do now?

And then you go back through your brainstem and you go, okay, what have I done?

And it usually was something that was not, it had nothing to do with anything that you thought that you were guilty of, it usually came from left field, and I never quite understood that relationship. For instance, one of the things that he was absolutely nutcase about was renewal of permits and payment of renewal of permits. And if one of those permit renewals was one millisecond late, he was on me like flies, literally, on manure. And I never could quite understood that, because I would do the paperwork and then it would sift its way through the system, either through the park district or through our own internal system, to see that it got filed, that the check got written and that got filed. And there was invariably, it didn’t make any difference if I started a year ahead of time, it would always be sort of last minute because it was always dollar-related in getting a check drawn, and he was absolutely insistent on that, and if we ever had any sharp words, it was related, it was related to his desire to have those things done faster than they could humanly be done. And didn’t wanna understand, or didn’t wanna know what the impediments to doing that was.

Did you still have the freedom that the other assistant directors before you had in the purchasing and the disposition of animals at the zoo?

Yes, I had all of the freedoms of the previous administration. The freedom that was a little questionable from time to time was that during the same time that I was assistant director, I was very active in the American Zoo and Aquarium Association. And he had been one of the founding members. I was essentially a non-director who was elected to the Board of Directors once. Then as a general curator was encouraged to go up through the ranks and I was told that I couldn’t, it was not in the institution’s best interest for me to work my way to the president of the association. And then several years later, I got back on the board, was in a similar position, they wanted me to make my way to be president of the association. And he was being kind, 100% dead set against it and said, you can’t assume that position, even if you’re elected to that position, if you’re elected to that position, this institution will not help you in any way, shape or form. You don’t have the title or the experience to assume that position of responsibility.

And I remember saying to him, with or without your help, I’m going to do everything that I can to assume that position, and I did. I did, and it was probably one of the most rewarding times of my life, and I don’t think he ever forgave me for it. I mean, even to this day, and I don’t understand why, because he never explained himself. And I always felt that it was in somehow, he conceived it as a threat, and I, you know, people who know me know that I am the least encountering person that you know in terms of threats, that I just like to get along and go along. But that was important to me because I had launched for the association, the species survival plan. I was very active in the national and international conservation arena outside of the zoo, as well as inside the zoo. It was a time of tremendous opportunity in terms of interaction with federal agencies. And I think, you know, jealousy would be too strong a word to use, but there definitely was a, I had crossed the line and I clearly had threatened something, whatever that threat was, but I’m not sorry I did it.

I’m not sorry I did it. I’m very pleased with the accomplishments that were made during my time on the AZA board and during that presidency.

And then we’ll talk more about that, but did you feel that that, were you still collegial though, in your day-to-day and things you had to do as a system director?

Oh, on a day-to-day basis, despite our differences, sometimes of opinion, we were, we had a job to do, we had a zoo to operate. We have funds to raise, we had programs to give, we had animals to manage, we had people to hire. Yes, we were, there were never was, I never felt uncomfortable. Our day-to-day interaction was very collegial.

When you first assumed the title of assistant director, was there any big concern looming that you had when you started the new position?

I don’t think in assuming the position of assistant director, I never gave it a second thought. I just thought it was a logical evolution of where I had been, where I’d come from, that I could use the skills that I had and just move on. I don’t think I ever questioned whether I was capable or competent to do whatever the task was, either specified or unspecified, that was before me. You mentioned that you now had new interactions.

One of that being with the zoo society, how did you specifically have to interact with them?

Was it at the level of use in the executive director, or was it things that you were told to do and you interacted with the zoo society?

I was in my interactions with the zoo society, I was pretty much guided on where I was to go, not so much what I was to do, but what the boundaries were, what the limits were, who I was to help and how I was to help them in terms of the zoo society being a friend of the zoo and being a significant supporter of the zoo. And I didn’t object to being guided at all, because for me, this was a new experience and I developed good friendships and relationships with people in this society, from the executive director on, down through the various, for the various specialties and departments. Now you talked about that there was budgets and there were these new capital improvements that were ongoing in the zoo.