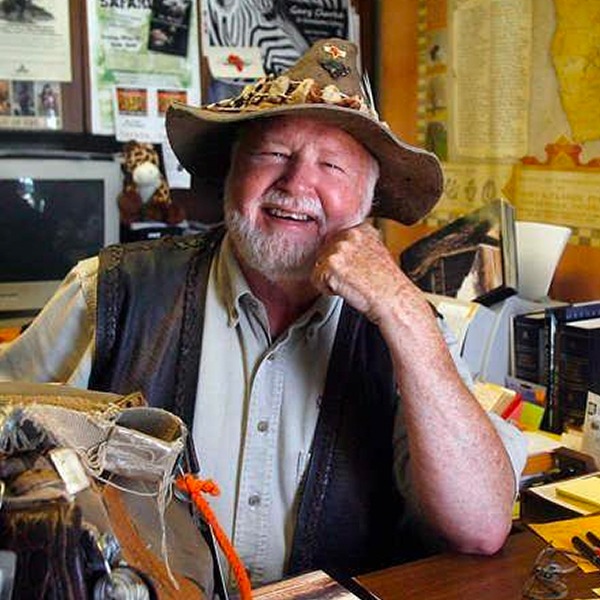

Gary K. Clarke, K stands for king. (chuckles) Just joking. I was born in Wichita, Kansas on January 19th, 1939. And grew up early years in Kansas, but then moved back to Virginia ’cause of my father’s job and then to Kansas City, Missouri. So I finished grade school in Kansas City, went through high school and started college.

What zoos did you see when you were growing up?

Well, the first zoo I am told that I saw was the old Central Riverside Park Zoo in Wichita which, quite honestly I don’t remember seeing it then. I remember seeing it in later years, but that probably was the first zoo that I visited. The zoo I remember most vividly from my early childhood is the National Zoo in Washington, DC. And my father used to take me there. And that may be where I gained my empathy for wildlife and animals. What a magical place, it was marvelous. And then when I moved to Kansas City, of course, as a youngster, as a teenager, ride my bike out to Kansas City Zoo in Swope Park. So I spent a lot of time there and all the things I’d read about animals came alive there at Kansas City Zoo.

So it had a strong influence on me. But I took the train to St. Louis just to see the zoo and I didn’t have a car. Didn’t have a car till I was probably 25 years old and went to every zoo I could just taking the bus or the train or whatever.

Now as a child, were you interested in working in a zoo?

Mark, as a child, there were two things I wanted to do in life. One was work in the zoo and the other was go to Africa. And I’d always had this fascination with wildlife and the animals of Africa and Africa itself always intrigued me. And my father, a wonderful guy, had polio, and walked on crutches, but he had a fascination with the world. And this is back in the 40s, so we didn’t have a television set or anything like that, but had a short wave radio and he would, at night, we’d get BBC and we’d hear Big Ben striking and then he’d get some African country, and he’d know what it was. And then we have these maps from National Geographic. And he’d show me on the map where we were actually hearing on the radio. Oh, it was so fascinating.

In fact, when I was seven years old, he got me my own membership at National Geographic Society. Now that’s long before they had these junior memberships, like they have these days, full fledge. So he’d get his magazine, I get my magazine. And that was really good. It encouraged me to read, and so on, so I attribute a lot of this to him, ’cause he was kind of a citizen of the world.

What kind of schooling did you have when you were progressing?

Standard and routine, I would say. Went to grade school in Alexandria, Virginia, Robert E. Lee School, whose birthday is January 19th, Robert E. Lee’s birthday. And came back to Kansas City and finished, I actually took seventh and eighth grade together at the time and went through De La Salle Military Academy in Kansas City, Missouri, and became a company commander, company C, captain of company C. And then went to Rockhurst College for two years and flunked out ’cause I didn’t study. It was so boring. Zoology was nothing but taxonomy. And I wanted to know about the living animal and what was going on, but I was working as a summer keeper, started in 1957, Kansas City Zoo. Tell me more about how your career began in the zoo world, that you got even that temporary job.

Well, actually I, on January 19th, 1955, when I was 16 years old, I rushed out to Kansas City Zoo in Slope Park and the director at the time was Mr. William T. A. Cully. And a very nice guy and well known in the zoo world at the time, started out at the Bronx. And I met him and, one of these kids, go in and raise your hand and say, here I am, God’s gift to the zoo world. (chuckles) And he said, “Well, that’s great, but you gotta be 18 to work in the zoo. Now that I think is probably a very valid policy, ’cause you are working with dangerous animals. So when I was 18, I rushed back out and they hired 12 temporary keepers for the summer, well, I say keepers, we were actually called zoo attendant or zoo attendant one or something. So my first day, I was so excited, my guys, I gotta get there, ’cause I’d been to the zoo all the time. I knew all the animals, knew those individual animals.

I didn’t know just about hippos, but I knew those hippos and those polar bears and those giraffes and I was so excited, what am I gonna get to work with today?

And of course the first day they give you a long pole with a nail on the end and a gunnysack and say, go clean all the papers in the parking lot. But that was good. That was good for me. And I thought this I gotta do. I’m gonna clean this parking lot better than anybody’s ever cleaned it. Of course you learn a lot about zoo visitors then too (Gary chuckles) when you clean a parking lot. But people pull into a zoo parking lot and if it’s clean, they take it for granted. That’s the way it should be. If it’s not, it’s it’s the first bad impression or a negative impression on the zoo.

So having a clean parking lot, having a parking lot is important, and having a clean one is very important in my opinion. Anyway, so during the summer, we did all these menial jobs, digging up broken shorelines and painting fences and cutting weeds and all this and once, about one of these young kids like me, one a week would quit, because it wasn’t the glamorous working with the animals thing. And to get out of the zoo in Slope Park, and to catch the bus, you had to go up over a hill to the bus stop. So we’d come in some morning and Joe wasn’t there. What happened to Joe? Well, he went over the hill. Meaning he’s gone, he’s outta here. And the old assistant director, Virgil Pettigrew, he was like a zoo foreman. He wasn’t really very scientific, but he’s the zoo foreman.

And all us menial guys, we were on the chain gang. And so if you’re on the chain gang, he’d say, “Let’s bow and arrow it.” Which meant bow that back and arrow that ass. Get that shovel and start digging this broken sewer line or whatever. So every week somebody went over the hill.

So by the end of the summer, I was the last guy. (chuckles) And Mr. Cully said, “Well, you’ve stuck it out.” It was kinda his way of saying who’s really serious about zoo biz?

And he said, “We’ve got a regular keeper going on vacation. We’re gonna train you for his job.” Oh my gosh, that was a dream come true. So I, and this was in what we called the north end with some miscellaneous animals, aoudad and tahr and camels, and tapirs, emus, so on. And he trained me and I felt pretty good about it. And he, this guy, he was a bachelor and he loved his animals and he knew them well and showed me how to shift the camels in the barn, and so on. And he goes off the next day for two weeks. And as you might expect, the animals knew maybe I was trained, but I wasn’t the guy. Those camels wouldn’t shift and the emu wouldn’t go in at night.

And, oh my gosh, I thought I’m a failure. (chuckles) But after a couple of days, I learned, I remember what he said and I was patient and I learned that animals accepted me and by he time we got back, things were going well. So then he goes around and inspects his whole area.

In other words, is he gonna pass, fail type thing, you know?

And he said, “You did okay, kid.” And he told Mr. Cully. And so that was it.

What was the zoo like though when you first started, what was its physical makeup?

It was, there’s no perimeter fence. It was one main, what they called, a lot of zoos had this, I guess, the main zoo building, and this was built 1909. And it was one of these combination buildings. There was a row of barred cages on one side of the interior with external barred cages. Most of those were for carnivores. So they had a pretty collection: lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, pumas, so on. And a few large primates, chimps, mandrill. The interior had a, initially a sea lion pool, but in 1950 they built the current sea lion pool.

They’ve expanded it and improved it since then. So they put hippos in the interior and a pool. And primates units for like red patas monkeys and green monkeys, mona monkeys. On the other side, a few reptiles. And at the far end was the elephant stall. And they had Asian elephants, two Asian elephants. Later they got African elephants. But that was the main zoo building.

And then outside, they had the bear pits and they were like the old postcards. We all have those old postcard, where the bars went up and curved over the top. But they had a American black bears, grizzly bears, polar bears. And then they had the grottoes built by WPA in the 1940s with giant anteaters and Patagonian cavies, things of that type. A nice monkey island built in 1946. It’s actually a pretty good monkey island. Molded flamingo pond. Then the north end, which I described a little bit ago, and in 1954, they built the African veldt, which was an old rock quarry that they then expanded and put a wall, barrier wall around to make about a seven acre display.

I’m sure Mr. Cully was thinking of the African Plains at the Bronx and he wanted to model it after that to some extent. He didn’t have lions over a boat, looking in, but he did have this collection of hoofstock. So together on the veldt, running together were zebras, eland, wildebeest, various cranes, and some waterfowl, ostrich, but we had to be careful how we managed it because we usually kept the stallions off exhibit holding yards, brought the mares in to be bred, let the mares back out on the veldt, deliver their offspring there, so on. Then he built a conical barn for giraffes, which were on development, separated by stockade fence. And then he brought in African elephants through Z. Handler. Young pair came in in 1955. So by the time I got there, they were youngsters, but I’d seen ’em come in, and so on, before I started working at the zoo. And then a couple of years later in 1958, he brought in the first gorilla, Big Man, through Dr. Deets Picket, a local veterinarian in Kansas City.

So, I mean, that was an exciting zoo for me. I wished it had more reptiles. Birds, they didn’t have a lot of birds, but some, mostly predatory birds. So it was a pretty neat.

Did you interact with the curatorial staff?

Did people stay on in their different areas?

Did they talk to one another? How did they interact?

(chuckles) What a marvelous question. There, and I don’t mean this disrespectfully, but there was no curatorial staff. Mr. Cully was a knowledgeable experienced zoo man, an animal man, and then became an administrator and a construction man and development man, everything you need to be to be a zoo director at that time. And the assistant director was Vigil Pettigrew who, as I say, was a great guy, but a glorified foreman. The most knowledgeable animal person of all was Benny Henry who had an intuitive feel for animals and was just a marvelous guy. And I learned so much from him. So there was no curatorial staff. Oh, Dan Watson was on the staff and he was the most educated.

And he was, we didn’t use the term nerd in those days, but if we had, he would have been the nerd. But he was a very positive, pleasant guy. And I learned a lot from him too. But then he went off to other zoos. So knowing there was no staff then, my heroes were the keepers. And I couldn’t wait to get acquainted with all these keepers who took care of these wonderful creatures. And in the mornings before work, instead of talking to animals, they’re talking about their car or the baseball game or their girlfriend or running out of money. And the mantra of many of them was quitting time and payday.

It was very disheartening. And it had a very small zoo library.

And during my lunch hour, I’d always be reading books up there, which they scoffed at, “Huh, who’s this kid reading all these books?

You gonna be a zoo director someday?” (chuckles) And I hadn’t even thought about that quite honestly. So I didn’t really learn much from them. But Benny Henry, yes, he was a wonderful guy. I learned a lot from him. But Mr. Cully called me in the office one day and he said, actually, you know, there’s a stint where I worked at Midwest Research Institute for two years, the reptile laboratory. And then when I came back to the zoo full time and he called me in the office one day and he says, “I know you love reptiles. And we only have a small snake collection. So what do you wanna do with your zoo career?” This is a penetrating question and a great question from this man, “What are you gonna do with your zoo career?” If it’s gonna be reptiles, then you can’t learn much more than you’d already have here.

But I know George Vierheller at St. Louis, and they have a big reptile collection there. And I could probably get you on there. Or if you wanna be a general zoo man, then I’ll let you work with every species we have in all areas of the zoo. Not only learn ’em, but be the relief keeper, and so on.” Wow, so I had to make a decision. So fortunately, that whole ploy, can I think about it tonight? (laughs) So I thought about it all right, I thought, I love reptiles, and I don’t mean to say that I’ve outgrown them, but gosh, now I’ll get to work with all these other fabulous species. I just wanna be a general zoom man. So I told him and so he let me work on all these other species, although I still love reptiles very much. So I was really fortunate.

Well, What were, so it sounds like you had a good relationship with him.

What other things did you learn from him and what were his strengths and his weakness?

He was a great guy. He and Mrs. Cully, there was a little office, a cubbyhole office in the main zoo building, but he didn’t use that. And I don’t blame him. But this is in the days when a lot of zoo directors had a residence on the grounds and that was part of the job. So at his residence, he developed an office in the residence and his wife, Mildred Cully, was his secretary. And by the way, they had a green ink typewriter ribbon. I don’t know if you ever saw these letters, anyway, when they would send out letters, they were green ink, which I always thought was kinda neat. And he would always sign these letters, zoologically yours.

And Mrs. Cully would type it out. They had one daughter, Kathy and it was not a question of me being a adopted son type thing. He wasn’t that kind of individual. But I think it was a question of him recognizing somebody who did wanna make a career out of this And like when the International Zoo Yearbook first came out, well, he gave me the brochure. And I got one and one of those originals. And he just, he did what little he could. There wasn’t a lot because the zoo was run by a park board, by Kansas City Park Board. But anything he could do, he would encourage me.

Probably the most important thing was letting me work with all these different animals. His strengths were, he knew he loved the animals, and he knew that the zoo revolved around the animals, and he knew it was for the public. And he wanted that zoo to a good for the public. He wanted that zoo to shine. And so he was somewhat of a stickler in this regard, but I think that was good. At the end of the day, this is one of these zoo situations where we had a dump truck called the manure truck that would go around to the various hoofstock areas where you stockpiled the manure after you cleaned the exhibits. And then the manure truck driver would dump it on and then he’d take it to the dump. And, boy, he wanted that truck washed every day, spotless at the end of the day, washed.

So I learned that a clean zoo is a good zoo, so to speak. And the zoo was free. There was no perimeter fence. And on Sundays, it was a 12-hour day. You start at 8:00 am and we keep the zoo open till 8:00 pm, because of the long summer days. But I loved that, I mean, just to be there the whole day. By the end of the day, the place, they used to allow feeding the animals and they allowed them to feed peanuts in the shell. Part of the reason was the concessions operator had a contract with the city was Sam Bornstein.

And, boy, he made a ton of money selling peanuts in the shell, but what a mess. On Monday morning, you were almost ankle deep walking through peanut shells, ’cause people would eat ’em too. So we’d have to get out the oversized firehoses, we’d come in early, come in at 07:00, work till eight o’clock Sunday night, take the bus or the streetcar home and be out there at seven o’clock Monday morning, the oversized firehoses. And those things are powerful. I mean, what water pressure. I’d hook ’em up to the fire plug and (Gary mimics fire hose spraying) blast that walks down, peanut shells clog up all the top of the drains and shovel those off. And peanut shells are really heavy when they’re wet too. But, boy, by noon, that zoo sparkled.

My favorite day to go to the zoo was Monday, because that was the lowest attendance day. And the place for sparkling. It’s a lot of fun.

What your question was, what are his strengths and weaknesses?

Weaknesses, I don’t know that I could cite any. He was active nationally in the old ACPA and served as president, 1962, I believe, something like that. When the old AIPE conference was in Kansas City. And that was one of the things I got to show visiting zoo dignitaries around the zoo. One of the guys selected to do that. But Mrs. Cully was so supportive of me too. And when I left to go to Midwest Research Institute, and then I came back, she’s the one that was, “I think we could find a spot for you” and stuff like that. She was always very supportive.

And when I had a chance to go to Fort Worth, Lawrence Curtis was director then, and it was a supervisory position, which today would be curatorial level. And Mr. Cully said, “That’s a totally different zoo, the way it operates, so I’d encourage you to go. I hate to see leave, but I’d encourage you to go.” Wrote me a nice letter. And Mr. Cully did, when I had a chance to go to Topeka less than a year later, then they were very supportive here too. So they were always very supportive. I’ll be ever grateful to them. So take me from this start at the Kansas City Zoo to the next phase leading up to when you became director. Well, I had that a stint at Midwest Research Institute where I got bitten by a red diamond rattlesnake.

And then, and I went to University of Missouri for two semesters and flunked out. And then back back to Kansas City Zoo. And then I went to Fort Worth in December of 1962. It was a fascinating time because the zoo had a lot of stars. Lawrence Curtis himself, Frank Thompson was assistant director. John Mertins was the curator of reptiles or supervisor of reptiles, they call it. Tim Jones was on the staff, later would become director of the Waco Zoo. Let’s see, Frank Kish was there for a while, but then he came to Topeka.

Anyway, and then they had animals stars. They had an aardvark which made Life Magazine. Had of pangolin, which made Life Magazine. Had pink porpoises, which Emily Hahn came and swam with. It’s in her book “Animal Gardens,” things like that. So that was a lot of fun. So they had an aquarium. So I got a little bit of experience there. They had a extensive tropical bird house with the little jewel box displays.

They were the opposite of Kansas City. Not much on hoofstock, more limited on carnivores, better on great apes maybe, but they were just building the then new herpetarium. And my first task was to help the rush to open the new exhibit. Every single goes through that, was to go help decorate and paint and finishing touches on the new herpetarium, which, as we talk today, is now gone, and the new MOLA, Museum of Living Art, is what they call the new harp is there But what fun it was, because that was a very innovative, imaginary building, imaginative building at the time. So that was fun, and to work with those guys. And less than a year later, during my first year there, the zoo hosted the midwinter AAZPA meeting. And Topeka came down, the park commissioner from Topeka, and park superintendent came down and made the offer to come to Topeka and when I started out, I wanted to be a keeper until I was at least 30, because I wanted that much time directly with the animals. And I felt I needed that to learn about the animals.

And then maybe when I was 30 or 35, I would be in a position to accept or think about curatorial level spot, and then maybe 5 or 10 years there. So in my 40s, I might be experienced enough, wise enough to be a director. So I started as a keeper at 18, and then at 23, I went to Fort Worth in the supervisor, curatorial level. And when I was 24, I got the chance to come to Topeka, which much too young to be zoo director, but I took it. I wrote a four page letter telling ’em everything that I felt was wrong with the zoo, knowing they would say, oh, well, we can’t do all the things you wanna do. So thanks, but no thanks. And they said, yeah, you’re right. Come on up. We need help.

And the Humane Society was trying to close the zoo. People in Topeka, if they’d say, after church on Sunday, let’s go to the zoo, that wasn’t the zoo in Gage Park. That was a zoo in Kansas City. Let’s get in the car and drive to Kansas City. That’s what they did. But I was already getting bald. I could bluff my way through, people thought it was older and wiser than I was. So that made it easier to try to function.

And I learned a lot on the job. And started on October 1st, 1963.

Why do you think they considered someone so young as yourself?

The previous park commissioner, who was out of office when I came, but was in office for many years, his name was Preston Hale and he did a lot to build the zoo up at the time. It was one of these park department zoos that sometimes it’s run by the park commissioner. It was one of these things. They didn’t have an official zoo director title or anything, but he loved it. And he used to come to Kansas City when I was a keeper and follow me around. And one of these, well, kind of a distinguished elderly gentlemen, always properly dressed, coat and tie. And he’d say, “We need a young fellow like you in Topeka.” I said, “Mr. Hale, I’m not near ready to do anything like that.” And he just kept saying, “We need a young fellow like you in Topeka,” I can’t help but think that after he, I can’t remember if he decided to retire or lost the election, but the new commissioner came in, Mr. Gooden, and the park superintendent was continuous from Mr. Hale to Mr. Gooden.

I can’t help but think that Mr. Hale might’ve said, “Well, why don’t you get that young fellow who was in Kansas City?

He’s now in Fort worth or something.” But I don’t really know, I mean.

When you accepted the position, did you have doubts about being named director at such an early age?

I probably wasn’t smart enough to have doubts. I was so excited. It was such a wonderful opportunity. It wasn’t that I was gonna be the boss. It wasn’t that, it was, I’m not sure how to explain it.

It was a feeling of because, Kansas City, there was no education department, but every time the zoo got a request for a talk, Mr. Cully said, can you go give a talk at this group or whatever?

And I was giving talks all the time to scout troops just on my own. But it was a feeling of being in a position to, and having a facility, needed a lot of work, oh my gosh. and having these wonderful, to help other people understand animals better. And it was just, that was the thing that excited me the most, I guess. So I didn’t, I wasn’t smart enough to think about having doubts until I got here. And the old guard, who were political appointees, had been running the zoo. And, I mean, with all due respect, they were older gentlemen from rural areas wearing their bib overalls, chewing the tobacco. And here comes a young whippersnapper.

They didn’t have much scientific basis in what they did. They would, we had one beat-up pickup truck. And so the foreman said, “Well, today, we have a special mix for our hoofstock, a feed mix. So I’ll go get that. So he’d be gone all day. So one time I said, “I’d like to ride along with you to see how they do this special mix.” Boy, he was teed off and incense. It turns out he drives south of Topeka to the co-op in the next little town and the guy there was a campaign contributor to the previous park commissioner, and they would chew the fat all day. And they needed to get the feed. It wasn’t that special.

Bring it back, well, we didn’t have the pick up truck all day long. I said, “I tell you what, let’s get some Purina Omolene.” (Gary chuckles) What is that? (chuckles) And they’d go around to one of these places, and they go around to the grocery stores till the end of the day to get the stale bread, the leftover lettuce leave, that’s how they were feeding the zoo. They monitored the sheriff department radio. And if there was a cattle truck wreck on interstate, the zoo rushed out to get whatever carcasses were there, with their permission, and slaughter ’em. And I’ll walk into the walk-in cooler, there’s was all these carcasses hanging there. Oh, they had a wreck down on Interstate 70 the other day, and it’s gonna feed the cats, these things. And they’d hack off a hunk and throw it into the cats who would know, and then the bones would clog up the drains. Oh, you know. You know that story.

(Gary chuckles) But the first day I was on the job, I had a little old beat up desk. I’m in the commissary smelling of fish throwing out, and all the cleaning fluids and all this stuff. And the phone rings. And there was a little thing in the paper, a new zoo guy, “Are you the new zoo guy?” “Yes.” (chuckles) “Well, there’s a prairie dog on my backyard and he’s digging it up.

Can you come and get him?” Oh, okay. What’s your address?

And whoever checked it out, it wasn’t a Prairie dog. It turns out, well, then the phone rang again, another call, I mean, all day long, the zoo had gone out and taken a chainlink fence, and put it into the ground that deep and put a guard rail around the top, and put prairie dogs in there before I got there. And they had all dug out, they were all over, not just all over Gage Park, they were all over that end of town. And everybody’s calling me the new zoo guy. Well, got a new zoo guy. Have him coming get ’em. (chuckles) Oh my gosh. That’s what I wondered.

(Gary laughs) Were any of the previous directors you worked for, did they ever give you any advice when you now took this new position?

You mean within a profession?

Well, the former zoo directors that you worked for before.

Did they call you up and say, I got some advice for you?

They didn’t do exactly that. Mr. Cully, he called, well, I called him after I got the offer. And he gave me a cautionary endorsement, sort of thing. He said, “They need a lot of work over there, but we think you can do it.” We, ’cause his wife has always, had her opinion too. So we would encourage you to take it. Lawrence Curtis and a lot of other people said, “Clarke, you’re not,” because Topeka was known in the zoo world somewhat as a political football, because the park commissioner had such a strong influence up to that point, the new one, Mr. Gooden, he didn’t. He wanted to be a business. I had a lot, yes.

I had a lot of colleagues, a few I knew at the time who called me and say, “We’re never gonna hear from you again. That is professional suicide.” If you leave Fort Worth or that new herp building and all the exciting stuff that’s going on there and all these qualified zoo people, which was right, there was a lot of stuff. And I used to take the bus, the Trailways bus down to Houston and see John Werger and go over to Dallas and see Pierre Fontaine. and Alby Turner was over in Dallas at the time, and all that stuff and it was great. They said, “If you go to Topeka, that is professional suicide. We will never hear from you again.” So they kinda wrote me off.

(Gary chuckling) When you got there as director, what were the top items, procedures, things that you wanted to address or enhance?

Well, number one was animal diets. I’m no nutritionist, but I could tell that this feeding garbage to them, it wasn’t, sometimes the food may have been acceptable. It was the concept, that’s number one, was the concept. And they were not balanced diets even if it was fresh produce sometime. Plus it was spending too much time. It was wasteful. And so the first thing we did was revise diets, make diet cards for the animals. So that even relief caregivers would be feeding the same. Keepers had a tendency to feed their favorites extra, or whatever.

Get that established, clean up the commissaries. Stop the carcasses on the road. Start getting the meat from Hill’s packing plant, which slaughtered the horses right here in Topeka, down by the river. Clean that up. Clean the zoo up. Clean the keepers up. Get some khaki uniforms. They didn’t have a lot of budget. But do some things to make, but the best thing was, there’s only, there were only, what, three keepers, three or four keepers and myself. And I had to be a keeper at least one day a week, because of the day off sequence, that we were short.

And so I had to fill in and be a keeper. Well, of course the regular keepers then would always booby trap me. First of all, they’d leave all the dirty jobs until it’s my turn to do their run. And then they would always put the hose, it was about ready to split, I’d hook it up, and all the rusty sewer lines, and all this stuff. So it was all these kind of games going on. But I caught on to a lot of those. Fortunately, I’d been a keeper myself. (chuckles) Caught on to a lot of those. But the best thing was to take this crew, I said, “Okay, today we’re gonna walk through the zoo like a visitor.” They only saw the zoo from behind the guardrail.

And it was get done as fast as you can, and go sit and have coffee and talk and, and so we’re gonna walk through zoo like a visitor. Now play like, we didn’t charge admission, any of that stuff, but I said, say you live in Topeka. You hear about the Kansas City Zoo, You hear about St. Louis, you hear about Denver. You hear about Tulsa. You hear about Omaha.

But what if somebody comes to Topeka and they walk, what’s it look like?

And they walked through and I said, “Yeah, we got some broken sidewalks. I’ll try to get those fixed, but what can we fix?” There’s mud on the sidewalks, the chainlink’s falling off the guardrail, branches fell down from the last windstorm are still there. When they would clean out the hoofstock yards and they had the manure trailer, it would bounce and stuff would drip on the public walkway and they just leave it. This typical stuff, I said, “Let’s at least make the place look as good as we possibly can.” Then I got ’em the new uniforms. Well, when we started making it look better and had a uniform, then people started saying to the keepers, hey, this place looks good and you sure look nice today. And so it wasn’t me telling ’em, it was the visitors telling them. So they started taking a little more pride in their work. So that was very important.

And then letting the people know, we have some fascinating animals here. We’ve got maybe not much, but a neat little zoo here. We need your support, come out and see us. And I started giving a lot of talks and so on. But this diet business, we had a couple of lion cubs born at the zoo who legs were all skew. And I knew of Dr. Mark Morris Jr. here in town. And they had this research lab called Theracon. And I called him and said, “I got a couple of lions.” And he came out and looked and he said, “Let’s take ’em to Theracon.” We’ll try some experimental diets.” That was how we got involved with the Morris, Dr. Morris and Hill’s Pet Products in developing the Zupreem diets.

And that all came, that’s something a small zoo can do. I mean, if you’ve got a resource in your community, join forces with that resource. So that was a good thing. And so I came in October ’63, and in April ’64 we formed the Topeka Friends of the Zoo, which we wanted to call friends of the zoo. And not Zoological Society. I felt it sounded too scientific and structured. And a friend of the zoo is a friend of everybody, or everybody would be a friend of the zoo, that kind of philosophy. So we started Friends of the Zoo and it’s been a great support arm since then.

Was Friends of the Zoo your idea or did people come to you?

No, it was my idea, I actually had a fella come to me though and say he’s with a local club, it’s not the Jaycees. It’s called the 2030 Club. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with ’em, but you have to be between 21 and 39 and you have to be in a given profession. And they do community service.

He said, “We wanna buy an elephant for the zoo.” I said, “Whoa, the last thing we need now is an elephant.” That’s like giving a subway to the city of Topeka, nice but what we’re gonna do with it?

I said, “What we need before we need an elephant,” I said, “What I wanna do, and I’ve been trying to figure out how to do it, we need to form an organization to help the zoo in many ways.” So that’s what I thought maybe the 2030 Club would be the best way to do it. Instead of me being a new kid in town, trying to find, say an attorney to draw up the bylaws of our corporation, an accountant or a banker to be the treasurer. Somebody, a printing business to do the newsletter. And on down the line, then the 2030 Club had all of these things represented in their membership. And I said, “If I could call on you folks to serve in these capacities,’ plus they had 45 members. I said, “If you were to either ask them individually to pay dues or take it out of your treasury, we would have 45 members to start this thing with. And then let’s see it grow. And make it family oriented and have family days at the zoo and all that kind of stuff.

So we did.

So this was part of your vision for the zoo?

Yeah, it wasn’t specifically Friends of the Zoo or support organization. The vision was get the community involved. And that was a good way to do it. That was one way to do it and a good way to do it.

Did you have thoughts then about education in the zoo and how did you try and start to implement this?

Yes, first thing was there were virtually no labels. So the first thing was to do labels. And not just the typical English name or common name, scientific name, range, food, longevity.

What’s a neat little behavior bit that maybe people could actually see this animal doing in this zoo?

So I try to come up with that kind of stuff. Park department made the labels, these old plastic labels for the router, (Gary mimics whining machine) type thing, you know, they were very good about letting me use some of that stuff. That was number one, but number two, I started giving a lot of talks. I’d talk to anybody and everybody: schools, civic clubs, church groups, whatever, just to get people interested. And it’s always, there’s groups always looking for a program, a free program. And I wasn’t asking for money, but I would like for ’em to join Friends of the Zoo and so that started it now.

And how important was conservation at the time you started or your vision for it?

Well, I believed in it. I thought it was one of the important functions of the zoo. I wasn’t really sure how much we in Topeka could do. We were one of these zoos that would receive injured animals. So we were a rehab facility for local species. We did work with Kansas Fish and Game and USDI. We did have trumpeter swans. In fact, we were the second zoo, I think, to hatch trumpeter swans.

And Philadelphia was right up about that time too. I wanted to do something with it, but quite honestly, there wasn’t a lot I could do at the time. The best thing we’d do with conservation, it was conservation education, was to get people aware of the importance of conservation on a local, national, global scale. But we were limited in what we could do then quite honestly.

Did you think about science and research as part of what the zoo would make out or?

Yes, and the science and research that we started out with was the ready-made one of the nutritional studies, but then I wanted to get Washburn University involved, even KU or K State. K State has a vet school. And so if we could cooperate with them in some way to help us and maybe we could help them with some programs for students, Washburn University. Mostly in the psychology department, having psychology classes come out in observational projects. Although later we were very involved with Przewalski horse because Lee Boyd was a student. And then now she’s chairman of the department of biology at Washburn. She’s been very involved with Przewalski horses. And San Diego Zoo and a lot of other places.

And that’s when we had an off-site conservation propagation center too, 160 acres out in the county with P horses and all kinds of stuff. But the other thing that we were able to do initially was some of these eagles, golden eagles and bald eagles that were brought in, because we were a park department zoo and necessity’s the mother of invention, to make a fight unit or aviary, we had the park department take two baseball backstops, the baseball back, put ’em together. So we had high enough and long enough, perch at each end, that eagles could even find in it if they were birds that could fly, if they didn’t have an injured wing or something. And so we did that in the 60s and the eagles started nesting. So we built nest structure and nest material. And of course they successfully hatched in ’71. First zoo to do that. You mentioned your breeding area.

That seems very unusual for a small zoo. Yes. Couple of things. One, we are a small zoo. Our zoo occupies about 30 acres in Gage Park, which is only 160 acres. And I was always conscientious about it. I want the zoo to override the park. I begged the park department to do a master plan for Gage Park. Well, they never would.

I said, I’d like to see the master plan in Gage Park and traffic patterns, and so on, before we do a master plan for the zoo, no. And drainage and service and utilities, all the underground stuff. Not the glamorous, the underground stuff. No, they wouldn’t do it. So we did a master plan for the zoo. Well, quite honestly, in my opinion, that’s the tail wagging the dog, ’cause we closed a major street into the park, so we could develop the zoo. And maybe that wasn’t right, but I wasn’t gonna let the zoo stand still, because the park department’s standing still. But we’ve always been limited.

So our first offsite facility was at Forbes, which used to be an air force base. And now it’s just Forbes Field. It’s the main airport in town. And they have some ammunition storage areas out there, which are now abandoned, but they’re big bunkers covered with earth and then big grassy area. They were not being used. We got permission to put animals out there. We had onagers, zebras, giraffes. So when we were limited in space for extra animals or new blood lines or animals in quarantine or animals to be shipped out, that was a wonderful thing.

Then we started the Przewalski horses out there. And that became so successful for us that we convinced the city to allow us to buy a farm in the county, 160 acre farm. And we got this regulation perimeter fence, got it approved, USDA. Not open to the public, and moved our horses and other animals out there. It was great. We were able to participate in a lot of conservation things then, that’s since been discontinued after I left. And the zoo is less capable of doing some of that stuff. But you’re right.

We were unique for a zoo our size to have something like that.

How did zoo exhibits change and evolve during your time?

We had a lot of old, a four-letter word I don’t like to use C-A-G-E, we had a lot of those, just the old barred cages. And I wanted to change that even though it’s a psychological thing with a visitor and a lot of chainlink fence. And I wanted to, mainly so that psychologically, the visitor felt better about the animals in the zoo. You know the story. You’ve got a zebra exhibit that’s this size and the chainlink fence all the way around it. And the visitors are down here. There’s a shrubbery row and there’s a guardrail, and it’s a chainlink fence. So one day you put the zebras in the barn, you come in and you take out the shrubbery row.

You take down the chainlink fence and you dig a moat. And then of course, before when you put the zebras out, you string some burlap along so then they’ll know where the boundary. Then you eventually take that down. Now the same visitor comes up and stands at the same spot, looks into the same amount of space at the same zebras and says, look, how much more freedom those zebras have, but it’s because they’re not looking through a chainlink fence. So we wanted to do that. The animals are doing fine, husbandry-wise, they were breeding, they were healthy. They’re living a long time. We felt we had adequate facility for the animal.

We just wanted to make it better for the visitors’ perception. And in zoo biz, that’s what a lot of it is. So that was one thing. The other thing was we had this old building. It was a greenhouse built in 1909. It was called a monkey house because winter, there was Monkey Island monkeys in there, and it was dull, dingy, smelly, it was everything the stereotypical old zoo facility is. So we converted that to the Animal Kingdom building, where we had glass-fronted exhibits for tropical birds or reptiles. And we had one for constrictors where the glass was recessed, it had rock work all around, the glass was recessed, had this huge log in for the constrictors to lay on.

We sawed it in two, glued it together on the other side of the glass and let it come out to the visitor. You could hardly see the glass. You could put your hand on the same log that the constrictor’s on. Yeah, that was, just little things like that, the interior lighting and stuff like that, which I thought was important. And getting in smaller creatures. Tarantulas, rhinoceros beetles, things like that. What we wanted to do was show representatives of each of the major groups in the animal kingdom. Although when he got to invertebrates, we couldn’t go much further than a few spectacular things.

But in this one building were mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and some invertebrates. And so we were trying to expand into people’s, individual’s mind that it’s not just the charismatic megavertebrates, but it’s other things too, come in and see ’em.

Now, what zoo professionals were either your mentors, or did you learn from and respect while you were in this position?

Well, certainly Mr. Cully continued, during his tenure at the Kansas City Zoo, to be, he would come over periodically. Walk, and do the rounds, make the rounds with me, and that was, well, I loved that, that was marvelous. He was great. And early, when I first came, Clayton Frye was, he was still at Buffalo. And then he came, and I met him at a conference. And when he left Buffalo and went to Denver, he drove and he stayed and spent the night in our house here in Topeka. Don Davis was very supportive. Charlie Hessel, before he was director of St. Louis, he used to run a pet store.

And then he was a reptile guy. And when I was a keeper at Kansas City, and I would take the train to St. Louis, then I’d see him over there. So we were kinda the same generation and we became buddies. So as he progressed up the line, he was very helpful to me. But actually, and Pierre Fontane, oh my gosh, he was president of AZA or at least program chairman or something. I came in ’63. He asked me to come to the AAZPA National Conference in Houston and give a paper. My gosh and, which was a great honor and kind of scary. But he was extremely gracious and cordial, but everybody I met at the time, it was good.

Fred Stark at San Antonio and Matt Marlin early on and Warren Thomas who was up at Omaha at the time, just every everybody was. It’s the days when it was like a big fraternity. It’s usually one zoo per town, maybe two, and even though you had a staff maybe you could talk to, it’s the only when you talk to other zoo people elsewhere that you get a lot of ideas and support, and so on. I was, for a punk kid just starting out, I really got a lot of support.

Now why was it important for you to visit a lot of zoos?

Oh, number one, that’s how you learn. Number two, I think the highest compliment you can pay any zoo person is to visit them in their zoo or aquarium. Number three, it’s to develop the rapport, the professional rapport.

And it wasn’t just how do you manage this animal?

How’s this exhibit designed?

It was drawing upon them and their perspective of zoos, their perceptions, their knowledge of the literature, and just communication. And I don’t know, it was just, and I learned so much every time I went. Took a lot of slides, kept a card file on things. That was a great education to me.

What was the first big development you did at the zoo?

What was your first big vision that you wanted to get accomplished?

Well, cleaning the place up and everything, as we said earlier on but that all revolves around one species, this first big development, and that is somewhat of a controversial species these days. That species is elephants. I could tell if when people would ask me a question at the zoo, I could tell if they were from Topeka or from out of town, by the way they asked me the question about elephants. If they were from out of town, they would come up to me and say, “Where are your elephants?” In other words, we’ve been around the zoo. We know a zoo’s supposed to have elephants.

Where are your elephants?

If they were from Topeka, they would say, “When are we gonna get elephants?” They knew we didn’t have ’em. When are we gonna get ’em?

Had it been my personal zoo, I would have built the rainforest first, because the concept for the rainforest was this geodesic dome, one structure with a ecosystem of live plants, birds and free-flight bats and free-flight animals roaming free, and visitor walks through. So you get multiple experiences. It wasn’t my personal zoo. It was the community’s. It was the people’s zoo.

So they were asking, when are we gonna the elephants, where are the elephants?

So elephants became the key. Well, if you’re gonna do elephants, then you should, a facility for elephants, with oversized drains, thick walls, high roofs, whatever, then you should think about what other animals that are appropriate for your zoo in that category that need that kind of requirement. So the others that jump to mind would be hippos, rhinos, giraffes, whatever, excluded rhinos, because they were more difficult to get. Hippos because, we chose hippos ’cause they were aquatic, or amphibious at least. They would be in water, they’re a bigger attraction, may be easier to get. And giraffes, so we settled on the three, the big charismatic vertebrates, megavertebrates, elephants, hippos, and giraffes. Then in the same building, we would then have had one section for large primates. Although we wanted to start with young animals.

Four chimps or orangs, or maybe eventually gorillas. So that building initially was called, as lot or more, in those days, the Large Mammal Building, but 10 years later, we changed the name and the whole theme of the building to Animals and Man, but 1964, I came in ’63. So in 64, we did our first master plan. And that consisted of the zoo, fixing up the zoo as it was, eventually phasing out the barred units for lions, and so on, bears, whatever. Kind of a central mall down the middle, the Large Mammal Building on one side and the rainforest on the other side. And the thought on that was, because we are a zoo that does experience a winter, then if it’s cold weather, people could come to the zoo, go to the indoor buildings, accessible to each other, close, and not go from polar bears to bison, and see the whole zoo. So city commission, city commission formed a government at that time. They were, we get the building design.

It was $250,000, which today is nothing, but in those days was a lot, especially for what we were getting. And was to be paid for by general obligation bonds, the city, and the city commission met every Tuesday night. So it was all set. Five commissioners agreed to approve it. The Friday before that Tuesday, a major bridge fell in over the Kansas River. Several cars went in, one fella was killed. So the mayor, this was a big tragedy for this community, mayor authorized all the bridges of the town to be inspected, half of ’em had structural failure, all capital improvements projects stopped. And, boy, I thought if we don’t get this thing approved now, as far as we’ve come, and as close as we are. And if we don’t get this project going, then the first big thing for the zoo, we’ll probably never get any project going.

So I went back and said, if the zoo pays for this through admissions, can we build it?

So that’s how the admission came about. We wanted to do an admission fee anyway, because I just felt it was better. We needed a perimeter fence. So you have to have a perimeter fence to get admission fee. And I just felt if people paid even mammal fee, it would just be better. So we started out at a quarter for adults, kids are free. But the first year we opened a building, which is 1966, it was still free. And after that, we started charging to build the building or to pay for the building through that.

So then we changed the concept to animals and man, same building, but we changed the theme, the graphics, the way we presented the animals to get the conservation element more in there and the impact of human population expansion in wild areas, on the types of animals that we see in these exhibits. And today, they still call it the Animals and Man Building. You mentioned, Gary, that you felt that cleaning up the zoo would be good for visitor services.

What other things did you wanna do for visitor services when you were director?

Well, obviously our zoo, when I first came to town in 1963, the first thing we needed to do was clean it up. Second thing was, well, the first thing was to get the animal diets and general management up to a professional level. And then the next thing was to clean the facility up, the public facility. And then wanted to improve the labels so that the zoo became more of an educational institution and more enjoyable visit. And start working on a master plan, so we could generate some interest and hopefully some funding for major improvement. There’s a lot of little things that, and we were totally dependent on the park department maintenance crew. And there was so much that needed to be done. I almost felt like I was imposing on these people, because they had whole park system.

They have, I don’t know, 45 or 50 parks in the community. And here I was wanting the welder all the time. I wanted the plumber all the time. I wanted the painters and whatever, and we didn’t even have a horticulture, so we had to call in the Park Department of Horticultures to come down. And I had to do that diplomatically, ’cause they didn’t want the zoo to be a thorn in their side. They didn’t want the zoo to be, oh, those guys at the zoo are bugging us all the time. We can’t get our regular work done type thing. But they became part of the team and they became proud of what we were doing.

And they would bring their families out and say, we worked on this at the zoo. We worked on that at the zoo. In fact, we even started having a, once the Friends of the Zoo was formed, that was another thing, ’cause then the Friends of the Zoo gave us funds that the city didn’t have for little things, such as a thank you picnic for park department employees and their families. So the summer in the evening, they would all come out and we’d showed ’em the new stuff and take ’em around and say, your father helped weld this, whatever it is. And that was another thing that I thought was very important. But education was high on my mind. And so in this new building, the Large Mammal Building, which we started planning in 1964, and then got approval, and it opened in 1966, we built an education room in there. That was the first official education facility of any kind, and all it was, it was a 60-seat classroom with these folding chairs with the little arm that comes up.

The old types of school chairs. But we had a slide projector and a screen. And the things those days were a big deal. And through the Friends of the Zoo, we started a zoo school program. That was one of the greatest things we could do, because number one, it expanded the education of the zoo. And we started a docent program too, which I thought was great. I think we were one of the first zoos to have a docent program, 1966 or so. Oh, and then I started expanding the staff, bringing in some people with some background in education who wanted to make zoos their career.

And with all due respect to the keepers we had and some of the old-time keepers we had decided that some of ’em would switch over to the park department and do something else, because the zoo was beginning to be more than they wanted to keep up with, I guess. But bringing in some other staff so that we could train the docents. And the docents would extend the zoo on a personal level. I thought that was fabulous. The zoo is the classroom, the animals are the teaching aides, but we needed people to help interpret this, so people would understand what the animals were doing and the value of the zoo and what was going on. And special programs for the blind. The Menninger Foundation was still a very prominent institution in our community then, the state hospital was very prominent. And for some of these folks with mental disabilities or whatever, the zoo was a great place ’cause the animals didn’t make any demands and accepted ’em as they were.

And it was wonderful to see all these folks come out. In fact, the zoo got an award from the Shawnee County Mental Health Association. And that’s the things a zoo should do, in my opinion. But building a new building, bringing the animals in and to raise the money for the animals, we had a program called Operation Noah’s Ark, in which, through the Capital-Journal Newspaper in town, we got a series of sponsors, mostly food products, a bakery, and a potato chip manufacturer, and a soda pop bottler, so on. And if you would save the product label, buy that, and save it and deposit it in one of our local super oil stations, each product label counted for a point and we would get 50,000 points, then the sponsors would buy a hippo for us or a giraffe or a pair of chimps or whatever we needed at the time. And the community responded. We would get at least 50,000 every month, sometimes 100,000 points. In fact, our last month we got 300,000 points.

And it was a fabulous thing, because the whole community was involved. And the hippo would come in and people would come out to the zoo and say, I ate 500 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to help earn that hippo. (chuckles) But getting people involved was great. Let me jump ahead just a moment, when we opened the, before we opened the orangutan exhibit, where we built these, structured these concrete trees for brachiation and perching, we got the visiting public, first the Friends of the Zoo members, and then the public come in to climb all these trees. And yet today I can go to the zoo, stand there incognito, see a father, come in with his little kids and say, “You know, when I was a kid, I sat on that tree perch right there where that orangutan is. (chuckles) And it’s a great thing. But Operation Noah’s Ark really brought the community together and got ’em involved. And we had other zoos contact us about doing that. And I don’t think it was as ever as successful as it was Topeka, ’cause Topeka’s a good zoo town. And they really got involved.

So now we were bringing in all these spectacular, fabulous animals that the zoo had never had, sometimes the state had never had. We had the first giraffes in the state of Kansas, had the first giraffe birth in the state of Kansas. And these are just wonderful things. You mentioned many ideas when you were young man.

Where were all these ideas coming from?

(Gary chuckles) Where did he get all these ideas?

I don’t know where, all these ideas came from, this just general, part of it from my travels to other zoos, part of it from reading about other zoos, part of it from wondering how to do things new and different that zoos hadn’t done, that could get people involved, that were in the parameters of a smaller zoo.

And sometimes people would say, why don’t we do this?

Or why don’t we do that?

I mean, people would come up with ideas. I’m not really sure how all these ideas come about. (chuckles) They just.

Did Friends of the zoo meet your expectations in the beginning and the goals you thought you wanted to set for them?

The Friends of the Zoo, in the beginning were fabulous. They were the epitome of a community support organization. They were citizens in different spectrums of our society, structure in Topeka who were willing to give of their time and talent, and if they had the finances, to even give of the finances. But it was their enthusiastic support of wanting our zoo to be special and to be better, that I think was so important. And I’ll be forever grateful to them for that. All the little things like, the money for the picnic, for the park department, maintenance crews, and so on, that was all very important. And then getting a publication out and eventually sponsoring the first safari and on and on and on. The zoo schools and the docents.

And we counted, we were dependent on the Friends of the, the gift shop, started a gift shop, things that we couldn’t do otherwise. The Friends of the Zoo did this. And so they were just fabulous in that regard.

How did the name, and why did it happen that the phrase world famous Topeka Zoo was coined?

Well, frequently I asked, how and why did we become the world famous Topeka Zoo?

And sometimes it’s with a scoff, (scoffs) what?

Topeka? World famous Topeka Zoo?

But I even had a guy who writes crossword puzzles puzzles for the New York Times call and say, “Now I’m doing zoos. I wanna make sure that world famous is part of your official title. (laughs) I said, “Yeah, it’s the world famous Topeka Zoo. That’s our official title.” (chuckles) We had a couple of things happened. First we had the first zoo to successfully hatch and raised an American golden eagle. That’s number one. Number two, we had an orangutan named Djakarta Jim, Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia spelled a D-J-A-K-A-R-T-A, it was a silent D. And he did a series of paintings. A lot of zoos have done this, but the park department said, there’s a park recreation conference in Hutchinson, Kansas.

Let’s enter one of those. I said, “Wait a minute. If you do that, people are saying we’re making fun of modern art, or we’re comparing apes with people. I mean, that’s not a good idea.” Oh, no, we’ll say that he’s an orang. So they put his name down as D period, D for Djakarta, James, his middle name, Orang, his last name. They entered it, the judges did not catch on. They evaluated it as a piece of art and it won first place, statewide art contest. So that became world news.

Air France Magazine did an article, a museum in California wanted to show his paintings. Remember the old television program “What’s My Line?” I was on “What’s My Line?” with some of this paintings. I presented one to the White House. The president of Steuben Glass in New York bought some. I mean, that’s when I wished that I had a PR department to keep up with this, ’cause I was trying to run the zoo, and all day long the phone’s ringing with all these PR things going on. But that’s a great thing though. Then we had monkeys get off of Monkey Island. (Gary chuckles) That’s not the kind of PR you want, but it went worldwide.

And Mike Le Roux was in Vietnam at the time. He eventually came back and worked his way up to zoologist, assistant director, and after I left, he was director for a while. He read it in Stars and Stripes, Pacific Stars and Stripes. So we started getting all these, this is long before all the internet and all this modern communication, all these clippings from all over the world. So at a staff meeting one day, I said, “Well,” I said to the secretary, I had a secretary by then, I said to the secretary, “Next time you answer the phone, answer it world famous Topeka Zoo.” So she did, everybody kinda, you know, so she did, and the person on the line was local and they said, “Hey, you’re right, because my cousin in Denver’s heard about us. We must be world famous. (chuckles) So it caught on. And what it was, it was a source of pride for the local community, but it caught on. It wouldn’t work someplace else because here’s this little old zoo in a Kansas prairie and they’re world famous, it’s great.

And when we borrowed the koala from San Diego back in 1986, they would call making arrangements and say, this is the other world famous zoo calling. I’ll accept that. (Gary laughs) So it’s been a great thing.

Now having said that, during your career at the zoo, what would you consider to be major events that you saw happen that affected zoos in general, and of course the world famous Topeka Zoo?

A major event during my career that affected zoos in general, and of course, the world famous Topeka Zoo, oh gosh. A major event, hmm. Well, I don’t know if it’s a major event, but I think economic impact had played a big role, what was it, proposition 13 or something in California, when park departments and zoos had to start restructuring how they finance themselves. It doesn’t affect us in Kansas as much, but that’s impact. I would say zoos, the concept of zoos breeding more of their own animals, and not bringing animals out of the wild, that’s been very important and we wanted to be a part of that and be producers, not consumers all the time. And another thing was early on, and when I was at the zoo early on, we, back in 1966, when we put in the large primate units, we used that glass. And that the glass, I think glass has been a great thing for zoos. You can be nose to nose with a 400=pound gorilla or a lion, with the king of beasts, or whatever.

I think that’s been a great thing. You had mentioned earlier a couple of names and situations.

What famous people have you met and how has it affected you as a zoo director, if at all?

Well, I met some famous zoo people. (chuckles) Marlin Perkins, one. Charlie Schroeder, who I always considered a famous new person, he’s a great guy and he came to Topeka, and he always kinda shrugged his shoulders and held his hand down and, “Well, I tell you, Gary, I’ve never seen a zoo do it quite like this, but it works.” (chuckles) That’s great. Ted Reed was extremely helpful to me. The one famous person outside the zoo world is this fellow named Ken Blanchard. He lives in San Diego. He is a management guru. He wrote this book, “The One Minute Manager,” and a lot of other books since then. And he came to town for a seminar and I was on the committee to help bring him in and elected to go out to the airport and pick him up and did so, and we had a great time at the zoo. And since then, he’s been on safari with me a number of times and mentioned me in some of his books and on his website and channeled people to me, and so on.

So that’s been very beneficial.

You’ve met presidents, haven’t you?

Well, yes, I have met some presidents. I hadn’t thought about that. (chuckles) In fact, when I met Jimmy Carter, when they formed the National Museum Services Board, and decided fortunately to include zoos and aquariums as part of that, and they had a 15-member national board, well, the zoo, AAZPA at the time, I’m not sure how it came about, but I was asked to be the board representative for zoos and aquariums. So I was the first zoo and aquarium guy on the National Museum Services Board in 1977. And the FBI did the big background check and all my high school buddies called and said, “What’s going on?” And, (laughs) God, that was something. And I guess it was okay. And so when I went to the White House to have a reception with President and Mrs. Carter, I wore my Zoo Power button, (mic thuds) and gosh, darn it, he never made a comment about it or said a word. I was so disappointed. (Gary laughs) And officially met him and shook his hand.

I guess that’s really the only one. We did present a orangutan painting to the White House when Nixon was in the White House, but he wasn’t there that day.

As director, what were some of your frustrating times as being director of the zoo?

Oh my gosh, as zoo director, what were my frustrating times?

I think it’s because of me as an individual personality, my frustrating times were not getting things done expediently. I don’t mean around the zoo on a daily basis. I mean projects, I mean the next phase of the master plan, I mean storm drainage system that should have been fixed years ago.

Why can’t we get this through the council?

Why can’t engineering department get what we need for this?

Those were my frustrating times. And the budget, preparing the budget every year, was the most difficult task. Fortunately, I had a good staff. I had a staff that could do that for me, at least outline it, and then I would have to do final approval or whatever. Those were the frustrating times. Sometimes if I’d had hair, I woulda torn it out. I mean, I know it’s what it takes to run a zoo and it’s necessary, but what I wanted to do the most was be at the zoo, be with the animals, be with the people, see all these students coming in, see these docent tours going around, see these zoo classes going, see people worried about animals, and not be worried about stupid budgets and stuff. But I know we had to do that.

So that’s a flaw in me as a zoo director, I’m sure.

When did you start the master plan and how did it develop?

Just out of your head or did you have other people helping?

Well, first of all, master plan is a general guideline and it’s not a master plan that stays forever. It’s a master plan that should be used as a guideline and then revamped because everything changes. And when I got there, and got all this initial cleanup done, then I wanted to do a formal master plan. And the one person that I knew, and had worked with, even though briefly, and he was a sharp guy, was Frank Thompson, ’cause he was then assistant director of the zoo in Fort Worth.

So I went to Topeka, I called him and said, “Hey, could you come up to Topeka for a few days?

And let’s sit down, and I’ve got some thoughts. I’d like to hear what your thoughts are,” and so on. And that’s how the first master plan came about in 1974, or 1964. And then once we accomplished the Large Mammal Building, which became Animals and Man Building, and we accomplished the rainforest, which are the first two major elements of the master plan and a lot of other minor things, then we redeveloped or redesigned the new updated master plan. And then we did even a third master plan towards the end of my tenure. But a master plan is not just a pretty picture that most people say, oh, this would be a new exhibit. It’s traffic flow and parking and service areas and delivery trucks and concessions.

And how do you haul the waste out?

And how do you get this animal crate in here?

And how do you get this dead animal out of here?

And it’s all that, it’s all these things. So that’s, and it’s financing.

And it’s, how’s the community changing?

How’s the political structure changing.

How’s the zoo gonna be managed in the future?

All of these things are very important. That’s why a master plan needs to be updated. But it would, the first one was Frank Thompson and myself. The next one was a lot of zoo input from the staff, ’cause we were developing a really super staff then, and I wanted their input. And also had consultants through zoo plant, so that’s when Charlie Schroeder came in, for example. And when we were doing great apes, had Terry Maple come up, and variety of people like that. So it’s gotten a lot of professional input.

What was your relationship with your staff, the curators, and how did you start looking at their development, their training, their upgrading?

One of the great things I had when I was director at Topeka was a staff. And the staff was superb, because they did so much. It was kind of one of these, they did most of the work, and I got all the credit. I always felt bad about that, because they did do the work. And I’ve tried to get them in positions so that they would get the credit too and make the presentations, or do the PR, do the press conference or whatever. And they were quite capable of doing that. But we started by bringing in graduates, young graduates with a degree in zoology who wanted to make a career out of zoos. Howard Hunt was our first degree person.

He went on to be curator of reptiles at Atlanta, but he started here, and I said, you know what, I mean, I knew he was a reptile guy, ’cause he was in Fort Worth when I knew him. We don’t have many reptiles here, but we do have a lot of experience at our res, so he hand-raised our first jaguar cub here. A lot of things like that, it was very important. Paul Linger came in, young graduate and started out here and became curator, assistant director and then eventually went to Denver, assistant director. John Wortman started here too. He went to Louisville and then back here for a while and then to Dallas and then to Denver. And Mike Le Roux of course came in. And I just felt it was important to let them have the professional freedom and responsibility to do what they needed to do.

And I didn’t want to interfere anymore, and I mean, they need to do it. And we’re a team and everybody knew what we needed to do as a team. But the key was they were all zoo people and they were all animal people and they loved it. Now they had computer skills, which I didn’t, Mike Le Roux developed great computer skills and Ron Kaufman, great education skills and all this business. But they were in zoo biz. And we had these, we’d take a staff picture every year and then we had a whole series of these staff pictures titled, “The Way We Were.” And it was fun, ’cause we started out with a handful of guys and the first picture’s black and white film. And then we built the rainforest, started taking pictures in there and taking ’em in color. Then we started getting female keepers.

And the staff expanded and it’s fun to see those pictures over the years. The staff has been so terribly important. A good staff is critical.

How would you describe yourself as director and how would your staff describe you?

(laughs) Oh, gosh.

How would the staff describe me?

Well, the way I would describe myself as director is, I don’t like, and I’m somewhat inefficient at budgetary things, finances, fundraising, it’s not my favorite thing. It has to be done. I can do that. I’m better at that. The drudgery of zoo biz, I don’t like that, and that’s just animal stuff, it’s animal stuff, and working with kids in education, and so on. How would my staff describe me? Oh, boy. Probably in a lot of different ways, to put it in who they were. (Gary chuckling) But always had a pretty good rapport. And we had a lot of people go through here and move on to other zoos.

And I was always proud of that fact, that the training in Topeka was accepted by other zoos as being professional and helping making them qualified. But whenever they would be in the area or come back or see me at a conference, it was always, hey, I really loved it when I was there. And how are things going, and so on. So I feel good. It’s always been a very positive thing.

You talked about development of the volunteer staff, how did the docents develop?

Was it a concept that you thought about or had seen and how significant would you say their role was in moving the zoo forward?

Well, the paid professional staff was very important, but in a different context, but just as important, were the volunteers. I mean the docents and our zoo school teachers, my gosh, without them, our zoo never would have, would never have reached into the community on a personal level and extended the zoo into the community as much as we did without the docents and the zoo school teachers. I always thought that giving tours of the zoo is great. I love to do that myself, but I couldn’t do all of ’em. And to have, it started really through the junior league here in town, because these were young women who, many of them were able to give time during the day. If they had young children in school, then they had time during the day that they could devote to volunteer activities or community activities. And so we wanted the zoo to be one of those desirable places to be. And with our staff conducting the classes, the docents loved the classes.

They loved going to these classes, learning about the animals and about zoos in general and our zoo and history of our zoo. And so that just kinda grew and it became almost a prestige thing to be a zoo docent, which was great. But then they did so many things beyond that. They’d always have a Christmas party for the staff and we should be having parties for them. They were having parties for us. And a summer picnic for the staff. And then they would bring their families, their husbands and their kids to these functions. And so that was a great thing.

But that was terribly important for this zoo in this community. I think it was one of the key things that helped really make the zoo what it was within the community. So I’m always grateful. I’ve always be grateful to those folks. And today, yet today, I’ll be someplace, there’ll be a young professional, dentist or, I don’t know, or a financial planner, and they’ll say, “You know, when I was a kid, I was in zoo school. I got a picture of me when you came to our class.” (Gary chuckles) It makes me feel old, but it makes me feel gratified. And I trekked down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon one time, and it nearly killed me. I don’t know, it was a terrible thing, ’cause I’m not really that good at physical conditions.

And I got down there and I was exhausted laying on the floor of the Canyon exhausted. And the rest of the guys said, “We’re going down to the trail to see a waterfall.” And I said, “I’ll just stay here and watch our gear and stuff.” And this park ranger came through and nice man in his uniform, young guy, looked at our permits and he says, “Hey, you’re Gary Clarke, aren’t you?” And I said, “Yeah, I’d rather not be right now.” And he said, “You know, when I was 12 years old, I lived at Topeka and I came over and you took us on a tour of the zoo and the docents gave us this and,” and that’s why I decided to be a park ranger. Oh, my gosh. That kind of thing makes it all worthwhile.

What was your relationship at the beginning with Friends of the Zoo and did it change over the years?

Relationship at the beginning was fabulous and it did change over the years. Friends of the Zoo was a group, as I said, initially, a group of really sincere, dedicated people in the community, volunteering time, effort, and sometimes finances and helping to expand the membership and the membership services to make our zoo better. Over the years, it seemed to change. The board changed. The concept changed. And quite honestly, they became a more internal self-focused thing. They seemed to be doing things more for them than for the zoo. That was a little difficult to deal with, but they were still important to us. And it wasn’t a totally unworkable situation by any means.

And then the city started pressuring me saying, now they’ve got office space at the zoo, don’t they?

Yep, well, we should charge them rent.

And I resisted that, because, well, now their members get in free, right?

Yep, now they pay dues to Friends of the Zoo, but then they get in free, which shortchanges the admissions for the zoo. We should charge them or they should pay us. And to me, that was getting awfully complicated. Now I know that society marches on, things change, the relationship between governing institutions, cultural institutions, support organizations, all changes. And maybe today you need all those contracts and things. That’s another one of my downfalls, probably as an administrator, I don’t like that stuff. I wanna shake hands. If people wanna be there and help the zoo and volunteer, we want you.

If they don’t, fine, if you don’t wanna volunteer anywhere, if you want to go volunteer at the history museum, that’s great, but the ones who wanna volunteer, let’s take the zoo and run with it. So I don’t know. That was a difficult part for me, it started changing. Talk about AAZPA. What was your impression of the AAZPA, the Zoo Association, was part of the parks department and association group. And can you tell us about this evolution of the AAZPA.

Was zoos breaking away from the Parks Association and all that time?

The AAZPA initially was formed, as I recall, in 1924. And it was a part of the American Institute of Park Executives, AIPE, and AIPE was the dominant organization, and we were the sub-organization. So all the conferences were held, they were AIPE conferences and zoos where a subset. A lot of zoo people, at that time, a lot of existing directors didn’t get the goal probably, but some direct, there were even some zoos where the parks director was the zoo director too. So it worked. And I think the reason that it was a subset of AIPE was because so many zoos in the early days were operated by parks and recreation departments, or at least parks departments before recreation became a entity that became part of parks recreation. Then AIPE evolved into or became NRPA, National Recreation and Park Association. So the American Institute of Park Executives expanded to become Park Recreation.

So that was a whole nother gamut of people. And AAZPA was still a subset of that. And I guess there were times when they would meet and the national conference would be held in the city. They didn’t even have a zoo at that time. Most major cities do now. And so they were very inconsiderate. So I think the feeling among AAZPA members at the time, it got to be, the feeling during the 60s got to be, well, we are chicks hatched in the wrong nest. We ought to be on our own, do our own thing, have our own organization, but we were tied in to them in so many ways, financially, membership-wise, publication-wise, we had some pages in their regular publication.

And we talked, one of the things where you talk about it a lot, but can we do it?