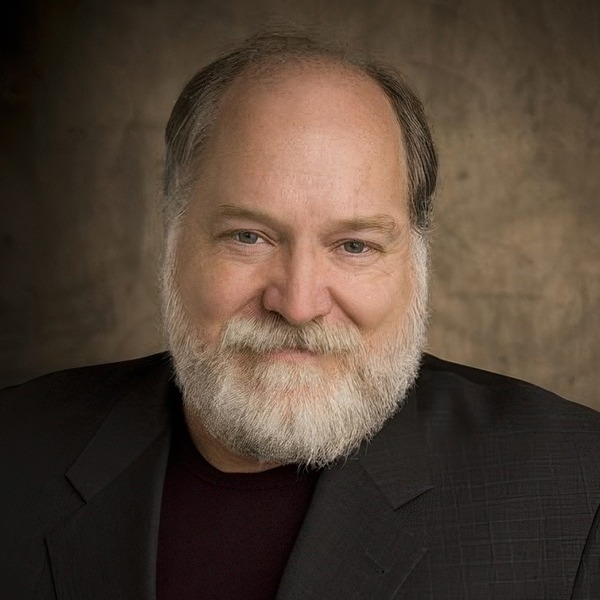

I’m Dr. Thomas P. Meehan, and I was born on March 26th, 1952 in St. Louis.

And who you were your parents, what did they do?

Dorothy and Michael P. Meehan. He went by Bud where dad was in advertising and he was the general advertising manager for the St. Louis Globe Democrat, one of the daily newspapers. And mom was a homemaker. Worked at home for most of her life. She did some work at our, my elementary school a little bit later on, but mostly, mostly a stay at home mom.

What was your childhood like growing up?

Were animals a part of your life?

Always. We had, we had dogs. We were, we were definitely died in the wool dog people. And, you know, we had, we raised hunting dogs. Dad was big into hunting and fishing and, you know, like a, like a lot of folks, my, my brothers were always bringing home, you know, the odd baby robin or snakes, squirrels, various things. I was, the, the joke is, especially my, my oldest brother was the one that always brought home wildlife and I always took things apart and to see how they worked.

And he became an engineer and I became a veterinarian. So How many children were in the family and where were you in the, in the order?

I was the fourth of five kids and they were real spread out. And my, my sister, the oldest, my sister Nancy got married when I was six. So, so we were kinda spread out in years. So I mostly grew up with my, my younger brother who was three years younger and my older brother is four years older. And were zoos. . .

What zoos did you see growing up?

What, what impression did they have on you?

Well, I mean, like most people that grew up in St. Louis, the St. Louis Zoo was a big part of, I mean, it was only the major attraction in St. Louis and we always were regular attendees of the zoo. I have pictures of myself as a, as a little guy at the zoo. There’s a picture my mom had of her when she was pregnant with my older brother walking through the zoo and being by some of the historic red rocks areas that are, that are still there at the St. Louis Zoo.

So what kind of effect did going to the zoo as a kid have on you?

Childhood memories?

Well, uniformly good childhood memories of the zoo. And, and again, back in the day, that’s one of the things that’s, that’s changed a bit now. I mean, I, I think anybody growing up in the fifties and sixties and even into the seventies, zoos were just, there was always a positive vibe about zoos. If a newspaper wanted to know something about wild animals, they talked to somebody at the zoo because they were the respected experts and they, they were just pretty uniformly seen in a positive light. And, and so that’s the way, that’s the way I, I saw the zoo when I was growing up.

And what kind of schooling did you have after high school?

Well, after, so, so when I was in, I, I went to I parochial school, a Catholic grade school through eighth grade, and then did two years of a Catholic high school and then switched over and graduated from a, a public high school. But around that, around the time my late high school time was when I, I first got experience working in, working in a hospital, human hospital. Some, a friend my sophomore year in high school, you know, had volunteered in a hospital. So I was kinda what they call the candy stripers and volunteered and, and got interested in medicine that way. And, and that sort of translated in me and of combining my interest in medicine and, and my interest in animals in looking at vet school. And So you went from high school to vet school or No, no, you need to, you need to have at, at the time it was a, a minimum of two years of college before you got into vet school. I think there was only one in my class that got in after two years. Most did three years or more.

There were a lot of people in my class that had a, a bachelor’s degree before they got into vet school, one had a PhD, so, so you do some college before that. And this was, you know, I think some of the folks at my high school had a, a slightly out of date idea of the requirements for vet school and said, you know, you really, if you wanna be a veterinarian, you really have to come at it from that agriculture angle, you know, it’s about horses and cows. And that wasn’t true at the time, but it kind of steered me into agriculture school. So I did my first couple of years at a community college and then transferred down to the University of Missouri. And I got, I was in a animal husbandry program in the agriculture school. And then you were accepted to university And then I was, and then I got accepted to vet school af after I applied. Now did any teachers along the way have any effect on your life as a mentorship or, Well, I, so I, when I was at University of Missouri, I in, I was enrolled in a program that they call the Honors scholar program. And, and what it meant was if you, if you were in this program, you, you didn’t have to meet requirements.

You could, you could sit down with your faculty advisor and make up your own curriculum based on what career path you were on. The downside of that was if you ever dropped below a b average, then all of those went away and you might have two extra years of college to get all the requirements that were now in effect. And so I was part of that program and so I met with my advisor who was actually a nutritionist in the AG school. And, and that’s how we charted our course. And, and actually once, once I got into vet school, because I had been enrolled in that program and I kept that grade point average, we threw all of our plans out the window and made my first year of vet school classes apply towards my degree. So I got my bachelor’s degree at the end of my first year of vet school, which some, some folks that I’ve talked to about that thought that was cheating. But I, but I, so I have a BS in animal husbandry and then, and then my DVM after that and, and that advisor, I, I never took a class from him, but I spent a lot of time, you know, going to his office and talking to him about plans and all that sort of thing. And I didn’t find out until later.

He told me later after I was accepted to vet school that he had written me a recommendation. ’cause he knew a couple of the faculty very well and I hadn’t even asked him for a recommendation because not having taken, you know, I thought he had, I haven’t had him for a class. I didn’t know him well enough to ask that, but he wrote me a recommendation because he thought it would help.

And, you know, maybe that’s what made the difference for me getting into vet school. So, So at what time, so to speak, in the, in your life, did you start thinking, I want to be a veterinarian?

It, it was really after I had worked in a, in a human hospital and seen medicine and worked with some doctors that I became intrigued by that and kind of put that together with my, you know, kind of lifelong love of animals. And, and the, the zoo part of it came a little bit later because when in order to get into veterinary school, you needed to spend time working with a veterinarian because how, how do you know you wanna be a vet if you don’t know what they do, if you haven’t worked in a veterinary office.

And so the way that was normally done was that you, you volunteered at a veterinary hospital?

Well, I was in high school, I needed money to go on dates to buy gas for the car, volunteer job, wasn’t gonna do it. And, and I also was, you know, from my experience going to the zoo, I was really interested in, in working as a, working as a keeper, potentially working in the zoo and getting my experience with animals and, and with veterinarians that way. And so, you know, right, actually before I finished high school, I applied for a job at the St. Louis Zoo and their response was, well, of course you wanna be a keeper. Everybody wants to keep be a keeper in the children’s zoo. You have to prove yourself first. So you did that by working in one of the refreshment stands. And so I spent a summer rolling hot dogs and selling balloons and making cotton candy and that sort of thing.

And that’s how you showed that you were a good employee and were dedicated, had a good work ethic. And then I got a call partway through that next summer, early on in the next summer that there was an opening at the Children’s Zoo. And so in early summer in 1971 started working as a keeper in the children’s zoo Full-time, So full-time in the summer. So it was sort of like what we would call a seasonal employee here at Brookfield. So this was normally what high school and college students did. They would work, it would be your summer job, and then at the end of the summer, the, the back part of the children’s zoo, the outdoor part of the children’s zoo would close seasonally and, and they would contract the staff down and run with just a, a part of the overall children’s zoo. And so a lot of the, the, the staff that were in high school or college would go back to school, come back and work at the Children’s Zoo on the holidays. But I did that basically all the way through my first year of VE school when we no longer had a, a more traditional summer break.

So your first job at the zoo is not as an animal keeper, but you become an animal keeper.

Yes. When about what year did you become an animal keeper?

A 1971. And it was just applying for it?

Well, I had applied for it the year before and they, it was, it didn’t, at the time, it didn’t require any sort of degree. As I say, it was more, more like what we have seasonal employees for here at Brookfield. So they, their qualification was, they wanted to know you were a good worker. And so that’s where I put in the work selling hot dogs and balloons and cotton candy.

What was your responsibilities as an animal keeper? Starting out?

Starting out, it was essentially animal husbandry, cleaning cages we had, and at, at the time, we, we knew more about, we knew less about contracepting big cats than, than we did about, you know, having them in a situation where, where you could get breeding. And so a lot of animals came through the animal nursery. And I think that first year we had something like something over 20 big cats, lions, tigers, jaguars, leopards, mountain lions. We had hyenas. These all came through the nursery. And this was a, a Marlon Perkins thing that, you know, establishing a nursery with dedicated keepers just to take care of newborn big cats, other primates apes. And so when they outgrew the nursery, they lived in the children’s zoo. So working with lions and tigers and leopards, the size of house cats was one of the big things that keepers did. And so coming from a family that were dedicated dog people, my exposure to 10 pound fills all was started with leopards and lions and tigers.

And so when I got into vet school and had my first introduction to house cats, it was like, oh yeah, it’s just like a baby leopard. Yeah, I, I, I get that behavior that’s just like a, just like a baby tiger. So I, my exposure was kind of backwards from what most folks experience.

And at the time were you thinking about other opportunities in the zoo world as you were doing this keeper job?

Or was this something you thought could be the rest of my life?

I love it. That was definitely, you know, when you’re, when you’re looking to get into vet school, you want a backup plan because not everybody that applies gets in. And so, so yeah, along those, you know, in those, my first couple of years of college, you know, that was something that I was thinking about while I was looking at vet school. And then when I finally got to the stage, you know, after three years when I got to the stage of applying for vet school, I actually expressed an interest in being a zoo veterinarian. And they let me into vet school despite that because I, I didn’t realize my graduating class would have filled every full-time zoo vet job in North America twice. I I graduated in a class of 70 and there were about 35 full-time zoo vets in North America at that time. So I didn’t, you know, I, I was interested in being a zoo vet, but I had no concept of, you know, how how big a pool veterinarians were versus how many zoo vet jobs were out there.

Did you have any mentors at this time?

Well, I, I, I spent time with, with Dr. Beaver at the hospital again, around the time that I, that I started. So by the time, by the time I was full-time in the children’s zoo, Dr. Beaver was established as the full-time vet at the zoo. And the, the keepers there, there was one keeper position at the Zoo hospital, and obviously they had, they only worked five days a week, so on the off days, a keeper from the children’s zoo would go up and take care of the animals at the hospital. And so, you know, I got to, I, I got to see some of the, the folks working up at the hospital and I remember being recruited as a, as a keeper to, to do things like monitoring, monitoring anesthesia, you know, counting heart rates and breath rates and things like that. So, so that was sort of my first experience, kind of behind the scenes working with a veterinarian.

So after you graduate from veterinary school, do you start a men an internship?

Well, there were, at the time there were two internships in zoo animal medicine, one at San Diego and one at National Zoo. And so I applied for both of those along with 60 or 70 other folks from across the country. And, and I actually was first alternate at National Zoo, so I was one person away from being the, the intern at national. And I didn’t, I didn’t realize this at the time, but they, their senior vet at the time went on a medical leave and then retired. And so right about the time I was coming out, they, you know, when I was had applied for the, the internship there, they offered the current intern the chance to stay on another year, and if she had left, then they would’ve taken the, their choice for the first candidate as well as taking me. And so, and, and so I was, I was really rooting for her to go on, move on to another zoo somewhere else, but she stayed put and I wound up not getting that either of the two internships and did a year of private practice. So I was in a practice, you know, a classmate of mine and I both went into a big multi veterinarian, small animal practice in Indiana. And, and then I applied, I applied for the internships again.

And now that I hadn’t done anything to advance my zoo career, I didn’t even make the final cut on either of those. So recognized that I needed to do something a little more academically rigorous to increase my chances in applying for other zoo positions. So around that time I got an offer from one of my small animal professors at vet school who had gone on and was running a small animal referral, an emergency hospital up in New York, and they were gonna have interns. And so he offered me a small animal internship. And so I took that move with my wife up to New York, an hour outta New York City and did a small animal internship. And then with that experience, my other veterinary experience and my track record at St. Louis, I was hired on as a resident. I, I got the residency at the St.

Louis Zoo, and I started that in 1979.

So the residency is different than the internship?

Yes, yes. The residency at the time, the residency was a two year program and it was the first one in the country that was, that was associated with a university, but actually located at a zoo. So I, I think I was about the 11th person to complete a zoo animal residency in the United States.

So during this residency and, and also the internship, were you thinking about how you would approach zoo medicine?

I, I think it, it’s a little bit, it’s a little bit like thinking about the, the Super Bowl at the beginning of each football game in the season. You’re, you’re engaged in what you’re doing now and learning everything you can and getting through your residency more than setting your sights on, you know, I’d like to be in this kind of zoo, or I’d like to manage this way or that way you’re engaged in learning everything you can, taking care of the animals at, at the time, even though, you know, it was a very large zoo with a large collection, there were only two veterinarians at St. Louis, there was Dr. Beaver who was the veterinarian and the resident. So you’ve, you’ve got your hands full, taken care of things every day. And then I also regularly went down to the University of Missouri to do things like residency presentations and those sorts of things. So you finish your residency and now you’re looking for a job full-time.

Yes. And how do you, how do you get the job at the Lincoln Park Zoo?

Well, the, you know, as a, as a veterinarian, it, it’s a, it’s a bit of, it’s, it’s determined by what your specialty is. If you are a small animal practitioner, you could look at practices anywhere in the country. A large animal food, animal veterinarian would be, you know, in a rural environment someplace as a zoo vet, you’re working in a big city. A big city, large enough to have a zoo that was hiring a full-time veterinarian. And, and around the time I graduated, there were three positions open. One at Zoo Miami, Miami Metro Zoo, one at Houston, and one at Lincoln Park. And so I could have wound up starting my career at Miami or Houston or Lincoln Park. I wound up interviewing at Miami and going down there and around that same time, interviewed at Lincoln Park.

Lincoln Park was my preference because with most of my family in St. Louis, there was a relatively much shorter commute to go home for visits. So I was, I was interested in Lincoln Park and I got that position At the time when you went to Lincoln Park, who was the head vet, Dr. Eric Ashkin. And, and the, they weren’t, they weren’t at the two veterinarian stage yet, but Eric had had some health challenges and, and needed some assistance. And so I actually didn’t go to work for the Chicago Park District and the Lincoln Park Zoo per se, Lincoln Park, recognizing that Eric needed a helping hand imposed on the Zoo society to create an assistant veterinarian position. And so the job that I applied for and got was as an assistant veterinarian. And I was technically working for the support organization, the Zoo Society.

What type of zoo did you find when you got on the job?

I, I, I guess one of my, one of my first experiences, that was one of the first things that interested me. ’cause I, I really had an attachment to the Children’s Zoo at St. Louis. That’s where I started out working as a keeper. It’s where I met my wife and I came to Lincoln Park and, you know, it was a much smaller zoo. It was probably a third, the size acreage of St. Louis and right downtown in the big city view of the lake. It was a beautiful place, but the children’s Zoo felt so familiar. You, when you went in, you, you went into an inside building and off to the right was the nursery just like St.

Louis. And then you went outside and this was only open seasonally, but you went outside and there was this area where there were lots of exhibits and different animals exhibited out there and there was artificial streams running through it. And, and it all felt very familiar. And what I realized after the fact was the children’s zoo at Lincoln Park was the first children’s zoo that Marlon Perkins built. And then when Marlon moved to St. Louis, he built one kind of along that same model that a lot of the same elements, but a little bit bigger and more modern at St.

Louis. And so that was the genesis of feeling very at home in the children’s zoo at Lincoln Park And in Lincoln Park at the time you were there when you started, who was the first director of the zoo and what was your relationship with the director?

Well, the director that was there throughout almost all of my dozen year tenure at Lincoln Park was Dr. Les Fisher. And Les was also a veterinarian. He started out as the part-time consulting veterinarian at Lincoln Park Zoo in the late forties. And somebody with a lot of, a lot of experience who, and moved up into the director position and had been the director there for some time when I got there in 79. And, and was a very good mentor, good to work for. And he had a veterinarian’s perspective, so, so I could rely on him, not just as the boss and the director of the zoo, but he, you know, had insight into some of the, the challenges of zoo animal medical practice.

What were your responsibilities as a young veterinarian?

When I, when I started the hospital, staff was myself, one veterinary technician and one keeper to take care of the animals in the hospital. So my responsibilities was running that staff of two people, but was responsible for the medical care of a very good size and complex collection. We had 2000 animals, half of those were mammals, half of those mammals were primates. So, so it was sort a, a medically intense job of supporting the medical needs of that entire collection.

How hard or easy is it would you say for a young veterinarian to work into the medical routine routine of a organization?

I think so. So Dr. Ashkin had been a consulting veterinarian there at the zoo, and they hired him out of small animal practice and into the zoo full time when they built the first purpose-built Zoo Hospital in 76. And so this was just a few years later. So I was really able to kind of pick up that program and move it forward. You know, I was the first per person there that had been through any sort of postdoctoral training in zoo medicine and, you know, so I got to put into practice all of the things that I had learned at St. Louis.

Was there any secrets when you first came to Lincoln Park of getting and working with the Animal Creek animal keepers to accept you?

Or had you thought about that philosophically before, Before I, I hadn’t really thought about that. It, it really was, you know, trying to develop their trust. You know, I, I remember jokingly when I, because I, I’m, I don’t know that I was aware of this, but certainly I I must have said more than a few times, well, when I was at St. Louis, we did it this way when I was at St. Louis, I did it that way because some of the, some of the keepers reminded me a dozen years later when I moved on to Brookfield, they said, now remember when you go over to Brookfield, you say, when I was in Lincoln Park, I used to do it this way. And when I was in Lincoln Park, I used to do it that way. So, so I’m, I’m sure I, I’m sure I referred back to my St. Louis roots more than a couple of times.

Were any of the animals at Lincoln Park where you started medically challenging?

And how did you handle it?

I, I think probably the, the biggest medical challenge and, and not based on animals being prone to illness or whatever, but just the volume of the collection. When I was at St. Louis, we had two, we had a pair of elderly gorillas, a handful of other great apes. And when I got to Lincoln Park, there were in the low twenties of gorillas and couple of groups of orangutans, a group of chimps. And so the, the number of great apes with their profile and, and the complexity of what we were able to offer medically was, was a big change. And, and I sort of, I sort of always felt like if there was a niche, I was mostly a primate veterinarian because those are the things that I remember taking up a lot of my time. And then we also had a rather successful breeding program with all the great apes and with the youngsters, ones that may need to be hand raised or need particular attention. You know, my subspecialty kind of became a grade eight pediatrician. So I, I’ve been around for, I’ve been around between Lincoln Park and, and here at Brookfield for something like twenty four, twenty five gorilla births, which is not an experience that pretty much anybody’s gonna get anymore.

So, so those are, you know, that, that, that was one of the big changes and one of the challenges that I really enjoyed. Now you were hired as a staff veterinarian, but you moved up to the head veterinarian position.

How did that occur?

Well, it, Or was it one in the same?

Well, I was, I was an assistant veterinarian, but Dr. Ashkin was, you know, because of declining health, he had a brain tumor and he underwent various surgeries and he was, we, we didn’t work together very long a after I started there. And so I was still officially the assistant veterinarian, you know, when Dr. Ashkin was still the head veterinarian in terms of his name on the door, but he wasn’t able to be at the zoo very often. So it was a while after he left that he officially retired. And I assumed that head vet position, but being, being the head vet at a place with one veterinarian is not a huge move up.

So your responsibilities to the collection didn’t change much?

N not too much. It was, you know, who I worked for and where my office was. But you know, those things changed after I’d been there about a year, year and a half. But I had been mostly on my own for, for that time.

How did you handle events when a routine procedure resulted in the death of an animal?

And can you relate the story of the snow leopard that died while you were doing a routine tranquilizing and lessons learned from experience?

Yes, that was a, that was a, an interesting case. The thing that complicated that was, so, it, it turns out that this was a, it was a female snow leopard, an adult that had a condition that we call eno occlusive disease now. And it was relatively common at the time and caused a lot of liver damage. And so this was an animal that we were simply immobilizing her to move her from point A to point B and doing a rou, doing routine things, trimming her nails. It was absolutely nothing of a, of a medical nature that required us to immobilize her. But because of this pending liver failure, she wasn’t able to clot blood normally. And so, and then to add one further complication, we had, we had had a request from a local TV station that had a, that had a, a news presenter that was doing a, it was doing a TV program on endangered species. And as part of that, you know, you know, it was basically about animals being trafficked in the wild.

And as part of that, they were interested in just as a sidelight a, showing what zoos were doing to help conserve endangered species. And so they just had a standing request, if you’re, if you’re doing anything with some of these animals, invite us out. So in addition to moving this animal from point A to B without any knowledge of her pending liver failure and her inability to clot, we were doing this procedure with a cameraman, a half a dozen feet away. And so we, you know, we went through, here’s how we get drugs into animals and here’s how this stuff works. And we’d done some of the interview stuff. We are towards the end of the procedure. We had already moved the animal, done our thing. The technician said I was, I was getting blood and, and she won’t stop bleeding and her neck is blowing.

And I said, just don’t worry about it, just hold it off. And he said, I am, but her neck is getting big. And I went to look at her and her neck was getting to be the size of a volleyball and, and she was having difficulty breathing, she was literally strangling. And so we were actually just finishing the procedure. So we got, we got our EKG machine, we got everything else hooked up. I wasn’t, things were compressed to the point where I wasn’t able to even get a trach tube back in or to establish an airway. And so wound up having to cut down through all of this swelling, which was all subq blood, got down in there, did a tracheostomy, put a tube in, and, and we were never able to get a heartbeat back. I I found out later that strangulation is something completely different than just cutting off an airway.

And it happens much more quickly than just an animal asphyxiating because they’ve got something plugging their airway. And she had probably been on her way out before we even started to resuscitate her, but at some point, after having gone through four or five inches of subcu hemorrhagic tissue and, you know, trying to resuscitate her and having blood from my fingertips down to about my elbows, I said, that’s it. I’m, I’m calling it, she’s gone. And, and that was the very first time I looked up from what I was doing and I looked up and I was facing the cameraman who had in the middle of this, packed his camera back up and come back in and was filming all of the drama associated with us trying to resuscitate this cat. So, okay.

So it wound up being part of a television show as well as being a losing an animal. So Now, so the press was present, but how do you feel about the press being present when procedures are being done?

Pluses and minuses of that at Lincoln Park?

Certainly press was involved in a lot of procedures, specifically when Sined was tranquilized. Yeah, yeah, I think so. So this one was sort of an odd case. It wasn’t one where usually the publicity is about you’re doing something unusual. We immobilized a gorilla named Sinbad at Lincoln Park who had gone over a decade without ever having been anesthetized because we were concerned about the risks. I mean, I think unnecessarily concerned and overly cautious about immobilizing animals. So we, it wasn’t a practice to do routine immobilization. So the fact that we got our hands on Sinbad because he was showing signs of dental disease and, and we were, we had to get in there and address the issue.

So that was unusual and it was an animal that, that hadn’t been touched in a long time. So we invited the press out. The situation with the snow leopard was different in that it was sort of their request. They just wanted to see, they just wanted to get some, what they call int VB roll of a procedure on an endangered species. So, you know, it was sort of our routine practice at Lincoln Park that if we had something high profile, that we might invite the press out. The same was done here even before my time at Brookfield. I remember that actually on the other side of this conference room, there’s a picture of a huge procedure with dozens of people involved in an elephant dental procedure that was done here. And when they immobilized her, they invited all the press.

And so there were three TV cameras, there were people from the Chicago Sun Times the Chicago Tribune. So it, it was sort of routine when you had something high profile and unusual that you would invite the press out to see it, Go back to the gorilla, tranquil for a minute, and you were concerned about a secondary procedure that was going to be done on the gorilla, and you were concerned about it. And you had spoken to your then director who didn’t seem to think it was a big deal, and he had a way of, he Had a plan Diverting the press from This. He, he had a plan. Talk About that. So one of the things, one of the things that is routine and kind of always has been in zoo medicine, since we have the opportunity to get our hands on the animals relatively infrequently compared with humans or dogs or cats, that we make the most of a procedure. So we are drawing blood samples for routine testing, we’re doing other things. And in this case, working with the reproductive physiologists that worked at the zoo, we wanted to collect semen samples from, from Sinbad because we wanted to find out more about more about gorilla reproduction. And, and so part of that procedure, it’s something that is done in, it’s something that’s done routinely in cattle and other species.

They use, they essentially put in an electrical probe and stimulate the animal to give semen so that you can test it. And the best way to do that in terms of the proximity of the nervous system is to insert this probe into the rectum and do the electrical stimulation. And as you might imagine, it’s not, you know, it, it’s not the best looking procedure in terms of being something that you want to put on tv. And so we were finishing up the dental work on Sinbad, we removed some teeth, cleaned up some things, and, and we’re pretty much wrapping up the medical part. And the doctor who was gonna do the semen collection was ready to start. And as we were getting close to that time, I was like talking to Dr. Fisher, Les we’re about ready, we need to do the semen collection. He says, and I’m saying this in the context of three big guys standing outside looking through the glass with their TV cameras, the, there were lots of press there.

And, you know, I reminded Dr. Fisher multiple times and, and finally went out and said, we’re getting ready to start, so what, what’s the plan?

And he walked out to the front, addressed all the crowds standing there and said, the, the reason we did this procedure, the the dental part is pretty much done. All of you are welcome to stay and watch while we just wrap things up. But if you’re interested, we have coffee and donuts in the library down at the other end of the building and you can go, everybody put down their cameras, they grab their notebooks and they vanished. And it, it was almost like a cartoon, you know, like you, you see the clouds of dust as this big group departed for the coffee and donuts. And Lester turned to me and said, you’re all set to go. So yes, somebody, somebody working from a, a lot of experience. Now you mentioned the director of Lincoln Park was a veterinarian.

Was this an advantage or a disadvantage to you?

I think it was, it was an advantage because I think you, you didn’t, you didn’t need to, you didn’t need to go into the background of why, you know, what it, what will this problem, what will this problem turn into if we leave it alone, what are the risks of anesthesia?

Those, those were all things that were part of his experience. So you could, you could kind of dispense with a lot of the more remedial parts of things that you would, you know, if I, if I was explaining the risk rewards equation to a keeper or a curator, somebody that didn’t have the veterinary experience, you could, you could skip past a lot of that stuff talking with a veterinarian. So, so yeah, it was good in that way. And, and, and Dr. Fisher wasn’t so much, he didn’t limit you in terms of, you know, I’d, I’d like to buy this EKG machine because, you know, it will offer us A, B and C. You didn’t get well back in my day. We got along without you. We just put a stethoscope. You didn’t get that. He understood what was needed to move things forward, you know, so you didn’t have to, it was like, I, I heard a, a, a veterinarian one time in a lecture say, we should endeavor in our careers to practice 40 years of veterinary medicine, not the same year 40 times. And you know, Lester wasn’t one of those, he, he was one that knew there were advances that should occur at each step and, and was supportive of those.

I think one of the things about the, the colleagues at Northwestern, there really was a, a battery of physicians that, as opposed to some of the things we’re dealing with nowadays where we’ve got a diagnosis, the animal’s been through the CT scan, we’ve done all this stuff, and we say we have an animal and it’s got this condition, could you help us fix that?

We would, we would rely on some of the folks from Northwestern back in the day to say, we’ve got this animal and it’s sick and we don’t know where to go with it. And part implied in that was, we also don’t have a lot of the equipment that you guys have in order to do that. So one of those was a female gorilla named Mumby who at, at Lincoln Park that had a probably early in her pregnancy, had something go wrong. She lost the pregnancy and I had been around at the zoo and treated her when, when we were dealing with those signs. And then unfortunately I went on vacation and, and I was outta town at the time. My associate veterinarian was Dr. Perry Wolf. And not too long after I left, maybe a week plus after we had treated her, following her, losing the pregnancy, she started having vague signs. She wasn’t eating well, depressed, lethargic.

And she really went downhill, I think on a weekend day one time. And, and so she called some of the folks from Northwestern and it, and it wound up turning into a, a marathon procedure, both of diagnostics. They did laparoscopy where, or endoscopy where they’re putting the scopes down and the, this is all equipment that they brought up from Northwestern and wound up figuring out that she had an infection in her, in her belly, in her peritoneal cavity and wound up taking her to surgery and, you know, finding that she had essentially all of her internal organs were covered in infectious material and they had to flush that out and, and clean all that up. And that whole, that whole process was something that would’ve been completely impossible without those resources.

Were you able to have the freedom at Lincoln Park to develop medical initiatives?

If so, what were they?

We, I guess my approach had, had always been to, you know, you’re, you’re trying to answer questions. Sometimes that’s just a one-off, you know, what, what do I need to do with this animal to treat this problem or, or diagnose this problem, which is more the detective side of it. But stepping back, one of the things that we had recognized was, while we had very good success with reproduction in the great apes, there was sort of a subset, particularly of the gorillas that had reproduced before but weren’t getting pregnant. And one of the things that we were suspecting was this cohort of the gorilla population was fairly overweight. You know, the, the, the euphemisms, they’re big bone, they’re, you know, those sorts of things. And so we wanted to put, I wanted to put some science behind quantifying exactly what was, what was going on, how, how did they compare with other gorillas. And so we had a nutritional consultant at the time who had done work with, you know, some pretty high level scientific work and in this case using heavy water, you know, the D two o, it’s, it’s water with an extra nuclei on the hydrogen side anyway, but it’s, it’s the, the process was you, you inject that, let it equal equilibrate over all of the water in the body, draw it out and, and what you can find out by knowing the animal’s weight and then subtracting the total amount of water in the body, you can tell how much of the body is regular soft tissue, bone, whatever, versus fat. ’cause fat has no water in it.

And so it’s a very precise scientific and kind of involved way to determine percent body fat. And then we also experimented with some other, or took some other measurements so that we could come up with a considerably less complicated but equally precise way of doing it. And so that’s an example. So we did that with a number of the gorillas, published a paper on it and, and determined how to make those measurements. And so we weren’t, we weren’t trying to solve an individual problems, but I had the freedom to, to take a step back and say, we wanna look at this population and try and determine whether obesity may be a problem and try and put a precise number to that.

Were you able to expand the veterinary staff during your tenure?

What were your goals?

The goals was to have a more, more complete coverage. You know, the, to have, nobody would really think about having a collection that size, you know, be the responsibility of one individual. I mean, you know, as I mentioned, Mumby mumby took place later. I was on vacation. If, if I had been on vacation and that happened in my absence when I was by myself, they would not have had it, it would’ve been complicated to deal with. So that’s one of the challenges to just having a, a one person show, but also being able to do a, a better job of addressing not just the, what we call the fire engine practice, just dealing with, you know, putting out the fires as they pop up. Trying to be more on the prevention side really requires a, a bigger staff. And so the first one of the things that I’ve done, you know, throughout my career is have a goal or have something that I would like to make happen.

And then I either push or watch for any opportunity to, to take that first step. The associate veterinarian, assistant veterinarian is a perfect example of that. Dr. Barbara Thomas at the time now, Dr. Barbara Baker worked with us as, as an extern during vet school, had obviously a passion for zoo medicine and once she graduated, she did some, some work at the Bronx Zoo and, and was, was very interested in getting a position. And she had the ability and, and the desire that I can, you know, if I can, if I can find somebody to help put me up and help support me, I could do this on a voluntary basis. And so I said, well, if you can be an associate veterinarian without me having to get the park district to find the money to pay you, which I knew they wouldn’t, I said, absolutely. And so she came and, and spent a few years with us as an associate veterinarian. And then, you know, as we demonstrated the utility of that we’re able to offer first her and then others funding from, you know, I was able to convince people within the park district that this was a necessary position to, to get on the books.

So you work at Lincoln Park Zoo till 1993?

Yes. And Then in 1993, you leave Lincoln Park to work at Brookfield Zoo.

And can you talk about what prompted your decision to change jobs?

That was interesting because I wasn’t, I wasn’t looking to go anywhere. I was happy at Lincoln Park, but one of the things, pathology, finding out why animals died, doing necropsies or animal autopsies is a critically important part of zoo medicine. That was part of my training at St. Louis. And we had a, we had a pathology program at Lincoln Park that existed when I got there using volunteers, physician MD pathologist, as well as veterinary pathologists from various institutions, from hospitals, from industry, from the medical examiner’s office. And they would come in, you know, a, a few times a week and do necropsies and it worked after a fashion, as you might imagine, the reporting and the complexity was a little uneven, but as, as times changed, particularly people that were, that were working on government research grants that were more generous, had more time, and they could, you know, take tissues and process ’em on their own dime, as those things started to dry up, people dropped out of the program, then it became more of a commitment for the ones that were left and then another would drop off. Anyway, by the early nineties, we had recognized the need to start paying for that service. And we were doing that through University of Chicago, where, which had been kind of the home base for the volunteer pathologists. We were providing funds through University of Chicago.

And then eventually that grew into a program where they actually hired an individual to help do the pathology service. But, you know, because we were trying to cobble things together, he had multiple responsibilities that probably each could have used a full-time person. And two of those were down at University of Chicago, and I was 10 miles up the road in Lincoln Park. So when we sent an animal down in a box to have a postmortem exam done, we would hear back from it much later or maybe weeks later, which really isn’t the service that you need. You, especially if there’s a group health concern, you need to know about that as soon as possible. And so we were, we at Lincoln Park were kind of looking for other opportunities. My predecessor, my at Brookfield Zoo, my colleague from across town saw some of the, he also recognized the importance of pathology, having had a lot of experience at the National Zoo where they had a full-time pathologist on the zoo staff and probably the first place to have one. And he recognized, he recognized the advantages, but saw some of the challenges I had and, and had no interest in jumping into that mix.

But we started talking about the new dean at the vet school at Illinois, who was a pathologist by training and had worked, had been the head of pathology up at the University of Guelph in Canada. And they had a relationship with the Toronto Zoo and pathology was an integral part of the resident training of the zoo residents at Toronto. So my predecessor and I are going, we have a dean of the vet school that gets zoo pathology. That’s, that’s a real advantage. And so he and I spent a year or a year and a half regularly driving down to University of Illinois and, and talking with the dean and developing the idea for a zoo path program that would be provided by board certified pathologist that worked for the university, but were based up here and could come to the different zoos to provide the service. So it started out as Lincoln Park at Brookfield and then by the time the program launched, it included shed aquarium. So we were actually to the point of selecting the person to run that program.

When I got a call from Dr. Phillips saying, Hey, have you ever thought about working at Brookfield?

I said, not really. Why do you ask?

And he said, well, I’m being recruited to go out to Davis, California to the vet school out there. They’re really interested. My wife is from there, so she’s really interested in heading out to California. And so it looks like I’m gonna be headed that way.

Would you be interested in thinking about Brookfield?

And so long story short, I did, they were building this brand new hospital and I came and I interviewed and that’s how I made the move from Lincoln Park to Brookfield. So it wasn’t, it wasn’t something I sought out, but, you know, because of that relationship that developed around working, collaborating to develop the zoo pro path program, the offer came and I wound up here and was here for a little over 30 years. So you are familiar with Brookfield and now you’ve come to Brookfield and you’re part of it.

What kind of zoo did you find when you came to Brookfield?

Obviously with my particular interest in, in the medical aspect of it, they had just built this state of the art hospital that was a real attraction. We were talking at Lincoln Park about what we can do to expand this, you know, 20 some year old facility and you know, here is one purpose built by somebody that has experience and has included all the bells and whistles, a much bigger campus. The ability, the freedom to live out in the suburbs, which I didn’t have being part of the park district at Lincoln Park. Employees had to live in the city of Chicago. So I had that freedom, different challenges and you know, it, it seemed like a, a real opportunity. Multiple veterinarians getting to work with some new things, dolphins, which I had never worked with before.

So Who was the zoo director at the time and what was your relationship with him?

Was he your immediate boss?

It, yes, Dr. George Rab was the director and I at the way things were set up at that time. I directly s reported to Dr. Rab and the, Dr. Rab was an amazing director and conservationist, but he was a super interesting personality and he could be kind of, he, he could be really challenging for people that hadn’t, hadn’t met him before. I heard stories of people doing job interviews and never actually seeing his face because he spent the entire time looking at papers and they, they looking at the top of his head. I had a very different experience because sometime before that, well, for, for a number of years I had routinely come out to Brookfield and taken part in veterinary procedures when they were doing something big here, mobilizing a bunch of big cats, doing immobilizing, all of the baboons on Baboon Island in one day. They would routinely, or, or doing elephant anesthesias, which I had experience with. I would get invited out to participate in that.

And even some things that turned out to be disaster management, it had a giraffe procedure that didn’t go well and wound up having to euthanize the giraffe. I had all those experiences and I had met George multiple times throughout that time and prior to my immediate predecessor getting hired, they had had some difficulties hiring on a new veterinarian and had some challenges in terms of communicating and essentially developed a reputation such that they put out an ad for veterinary position and nobody applied because zoo veterinarians, a relatively small field word, had gotten out about some challenges between veterinarians and others. And so their solution was to put together a search team. And George knew, George knew a handful of veterinary zoo veterinarians. Well, I was one that he knew from my time coming out for procedures. Dr. Wilber Amond, who was a director, assistant director at the Philadelphia Zoo, and Dr. Bonnie Rayfield, who was the veterinary advisor for the Oppy SSP George was the SSP coordinator for a copy and knew Dr. Bonnie very well through that.

And so he asked us all to come on board. He asked me to run to, to chair the search committee simply because I was really close, I could come out and communicate much more easily than the, the folks that were widely scattered. So through that process, I, I got to come out and, and work with Dr. Rab and basically say, here’s the problem you have, here’s why you have the problem. Here’s, here’s kind of how you’ve developed this reputation. And it was something that would’ve been, it, it, it would’ve been challenging to have that free conversation if he was my boss, but he wasn’t my boss. I worked at the zoo across town. And so I, I got to, I was in this sort of unique situation compared to all of the curators and the former vets is that I had, I had gotten to know Dr.

Rab and to talk at length about the program without being one of his employees. And so I, I think that was a huge help and, and I think, you know, may have been a factor in me getting the job after the person that was hired after that search, you know, when he decided to head to California, you know, that that may have been a factor in asking me to apply and selecting me for the position.

Was the medical staff at Brookfield larger than Lincoln Park?

Yes, yes. At Lincoln Park, 50% bigger. There were, there was a head veterinarian and two assistant veterinarians at Brookfield, and there was a head vet and an associate at Lincoln Park, roughly similar collections. But you did not start out as a staff veterinarian, you’re director of veterinary services at Brookfield Zoo.

Does this mean you’re no longer doing veterinary work, but only administration?

So I, I was, I, I can’t, I I can’t actually tell you what my position was. It might have been chief veterinarian or it was head veterinarian. The veterinary services thing wasn’t part of the title, but I was the, I was hired to, to fill the role that Dr. Phillips left, which was head veterinarian of this staff. I, I liked, I wanted to present a, a different model of veterinary care with the title of veterinary services because I felt like animal health was, animal health was a, a responsibility that was broader than just the vets. And, and there were things that we did besides veterinary medicine. And so I changed the name to veterinary services and so I was the head of veterinary services and there are always, you know, for the person that’s administering that program, there were, there was a staff of, so there were, there were two other veterinarians, there were three keepers and a fully staffed LA laboratory that had three medical technologists. And so it was quite a bit bigger staff. And so that, that does entail more managerial responsibilities.

But I was a clinical vet, as is the head of the, the program today still has clinical responsibilities.

Were you accepted by the new veterinarians and staff?

Yes, I think so. One of the new, one of the new veterinarians, actually, one of the very first responsibilities I had before I ever even officially started is there was, as Dr. Phillips was making the decision to go to California, there was also an opening for a second associate veterinarian. And so they, once he decided to make that move, they put the other hire on hold and, and actually invited me to come out while I was still working at Lincoln Park to interview candidates for the associate position. So, so for one of the associate positions was a, an existing one and, and one of the other, the, the other one was one that, that I helped select right from the get go. So, so one of ’em was brand new that I was familiar with. Right. Right off the, right off the bat. And the other was, you know, accepting of that as well.

As a director of veterinary services, did you have more opportunities to make changes in the manner in which veterinary medicine was practiced at the zoo?

Absolutely. I mean, you have the, I mean, part of it started with the, the hospital. The hospital opened about a week or two before I started. So I walked into a brand new building, but there was also a significant amount of budget that had been allocated for equipment that hadn’t been spent yet. So, so I was helping to equip the hospital and in terms of support, equipment, anesthesia, monitoring, equipping the laboratory. So one of the, the clinical chemistry analyzer that we had in the laboratory was a relatively, a relatively new piece of equipment designed by Kodak to do, you know, where you could put in a, a blood sample and a relatively small blood sample and get a whole ray of chemistry tests done on it. And it was such a new piece of equipment that after we were here and that was installed, we had people coming from human hospitals to, to see this for the first time because they were considering it for, for their operations. So, you know, we had the opportunity, you know, as we, as we moved into and kind of christened this new facility we had, you know, that that gives you much more than an incremental opportunity to kind of up your game. You know, you can, you can make a, a pretty big leap all at once in terms of the space and, and equipping that.

So I, I think in terms of surgical equipment, patient monitoring equipment, and particularly diagnostic equipment, those were things that, you know, we made a, a big jump right around the time we moved into the building. And then because of the space that we had available over, you know, over the coming years, we were able to seek out donations and look for equipment that we didn’t have, upping the game on ultrasound equipment, adding more modern radio radiographic equipment. And then, you know, one of the big ones was I was actually up on my roof shoveling snow one day and got a call from the head radiology manager over at Loyola about would I be interested in the donation of a CT scanner. And I thought about it a few minutes and I thought, I think there’s potential in this space and I think there’s potential with this donor. And I said, absolutely. And it took us a couple of years, some remodeling. We, you know, things moved along in fits and starts, but we were, I think only the second zoo in the US to install a CT scanner. And, and that has really been a game changer.

And the zoo has been a big proponent of getting that installed as the standard of care in lots of zoos and even developing a database to help radiologists interpret zoo radiographs or Dr. Mike, who has since become our director, got a grant through the institution of mu museum and library services to develop a zoo animal radiology database. The idea behind that is getting normal exams, whether they be radiographs, ultrasounds, cts, mrs.

And developing a comprehensive resource so somebody can go out and say, what does a normal, what does an MRI or a CT on a normal aardvark look like, or a gorilla or a dolphin?

And, and that’s just, that’s been going on for a couple of years now. The, the grant was a collaboration among a number of institutions. Everybody has pooled their normal exams, hired a database manager to, to essentially oversee the whole operation. And it’s probably sometime early next year it will go live as a resource for zoo veterinarians around the world to rely on. And, you know, part of that is built on some of the diagnostic capacity that we’ve been accruing Since this building opened. You had published extensively.

Was there pressure for you to publish or was this something you wanted to do and why?

I have not published nearly as extensively as a lot of my colleagues have been accused of having an ink allergy. But, but I’ve, I, I hope I have contributed to the field, you know, particularly in areas of research, some of the unusual cases, things like the gorilla that we perform brain surgery on and some of the other important cases. But I think I, I’ve had much more to do with creating opportunities for, and programs that support other folks that, you know, put our collective group between us and our colleagues and partners at the University of Illinois, you know, pretty much at the top of the heap in terms of contributing to the zoo veterinary literature.

Based on your many years at Brookfield, what impact on the field of zoological medicine did working at Brookfield provide you?

I, I think a, a very supportive environment in terms of being, I mean there, there’s a real cost in terms of resources involved in supporting a veterinary program at this level, whether it’s adding the zoo pathology program, adding veterinary staff, upgrading equipment as new thing, all the things that I talk about is, wow, the gee whiz thing, that Kodak machine, all of that stuff is long gone because the technology advances so quickly and, and throughout my time here, under different directors, under different managers, we’ve been able to, we’ve been able to demonstrate the, the advantages or the value to that program such that they’ve been able to, to support aiming the donors in that direction and, you know, providing the ongoing operating support.

Can you discuss your role with the Great eight Heart Project and how you became involved?

The Great Eight Heart Project, I, for me, it really started all the way back when I was at Lincoln Park and I was, I was named as the veterinary advisor to the Gorilla, SSP, I think as the first veterinary advisor. And we’ve had some, some other associates, other veterinary advisors, and, and now it’s a group of four of us that, that share that responsibility. And one of the, one of the first things that I, that I did, because it’s data that’s more available, you, you wish you knew more about what’s going on with these animals in real time. But data that was available retrospectively was looking at necropsy reports, pathology reports on why animals died. And we recognized a, a couple of things. One is that gorillas, the most old adult and older adult gorillas died of cardiovascular disease. And if you tell that to a physician, they say, yeah, I get that, you know, heart attacks are a big deal in people. Cardiovascular disease is a, a really important cause of death.

But the second thing is they almost never get heart attacks. The, the, the same sort of myocardial infarct, the thing that, you know, is characterized as a heart attack in humans. They have other cardiovascular disease that are not unheard of, but less typical, more unusual in humans. And so we had an interesting, an interesting issue, and I gave a presentation in 93, 94, somewhere in there where we said this, this seems to be one of the key areas health wise in gorillas, if not the chief one. We need to, we need to find out more about this. And particularly at, at the time I talked about that nobody had diagnosed these cardiovascular problems before the animals died, you know, which makes treatment pretty difficult. So we said, you know, we need to, you know, it’s certainly a challenge, but it, it would be good to do more diagnostics, particularly echocardiograms to ultrasounds to see what’s going on with the heart, to try and figure out how this thing progresses. And that led to discussions.

It, it started a, a, a group looking at Gorilla Health and then one of the, one of the other veterinary advisors who was particularly interested in that topic, right from the get go, Dr. Haley Murphy, who’s currently the director at Detroit, Haley, put together a grant to look at this issue, but not just in gorillas in other great ape species as well, because we, we put on, we put on seminars and symposiums, and we got together with colleagues and, you know, we had recognized this thing as a particular problems in gorillas. And the folks that dealt with orangs said, yeah, we see that too. And the folks that dealt with chimps said, yeah, we see that quite a bit and Bonobos. And so, you know, it grew from my interest in, in sort of one lane focus on gorillas into recognizing that at a, as a bigger problem. And Dr. Haley has just taken that and run with it. She started the, got a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to start the Grade A Park project. It started with hiring a database manager who is still with the program. And there have now, you know, fast forward, I was just at a grad, a heart project meeting few months ago, and, and there are well over a thousand echocardiograms from great Apes.

I mean, there’s a huge number and it’s, and it’s become, you know, Haley and I talked about this and said, you know, I’m not sure if we’ll ever get anybody to do echos on their gorillas. And thousands have done it. So, and, and putting that in the form of a database, collaborating with, you know, and this gets back to the, the various consulting collaborators. There’s a group of physicians, MD cardiologists, as well as veterinary cardiologists that serve for each particular species. There are people that are experts in and will interpret. So if Albuquerque or St. Louis or San Francisco does an echo on an ape, they can send it off to the Great Ape Heart Project and they will get an interpretation from an expert in that species that’s a boarded cardiologist that can, and, and give them some recommendations on what’s going on with the animal, normal abnormal and treatment recommendations, and then follow on things. They did another grant focused on pathology where they actually hired a postdoc veterinarian that was a pathologist to look just at Great Ape Hearts.

And she did that for over a year and now has finished that grant and is going into that specialty full-time. So, so the, the bottom line is we’ve, so I, I was involved in, in this process sort of from the beginning and, you know, now I’m, you know, one of the old guard, kind of a hangar on, on the Great Ape Heart Project, but have sort of been there since before the beginning. So, so that’s, that’s how I got involved in that and that’s how that program has evolved. But it’s just, again, it’s like seeing your kids do things and have accomplishments that you never could have dreamed of for yourself. So You had a bigger staff at Brookfield Zoo Zoom.

How would you describe your management style?

How do you think they describe your management style?

That’s a good question. I think, I think what I, what I tried to do was give folks freedom and direction and, you know, allowed in, you know, I have a particular interest in this species or that research. I think I tried to help facilitate that, not not necessarily focus it and say, no, that’s no good, you know, I want you to work on this, but to try and be supportive and help find the resources to, to do things. I also, I think one of the, one of the big things that I did a few years back, probably well over a, a decade ago now to, from a management standpoint, I needed to distribute some of that administrative load. So in terms of direct reports, I had, I had overall oversight of the program, but had one of the associate veterinarians be in charge of the laboratory side and the other one in charge of the veterinary technician side. And one of the things that I, I recognized along the way, you know, is like, there’s, there’s too much work there. You know, we need more, we need more veterinary staff because we were all involved with administrative stuff as well as the veterinary care and, and looking at options. We said, you know what, maybe, maybe let’s follow the lead of private veterinary practices out there.

And, and they’re not having the veterinarians, you know, the clinical veterinarians aren’t responsible for managing staff and oversight. They have hospital managers. There’s actually programs that certify hospital managers. And so what if instead of hiring another veterinarian, we hired a qualified hospital manager and reduced all of those workloads by everything that you’re putting into staff management to hr. And so we were one of the first places, and that’s, and we still have, you know, the hospital manager is now the department operations manager. And that’s been a very successful model and one that a number of zoos have picked up because, you know, recognizing that HR and personnel management is, is not something that necessarily is best served as something that you kind of do on the side. You know, it was like back in the day, I’m a clinician, but I do pathology on the side. So I let all the, I let all the animals that have died over the week.

I let them gather up and then every Friday I carve out some time, well, then you don’t get good results because animals deteriorate. And pathologists, our professional pathologists now think that something is really old if it’s been dead for 12 hours. And we used to let them wait days. So the moral of the story is, you know, clinicians may not make the best pathologists and clinicians may not make the best personnel managers. And so by creating a whole new position of hospital manager, we were able to free up veterinary time by taking something off their plate that perhaps wasn’t being handled in the best way.

How, how did you shape the zoo conservation programs as it relates to veterinary medicine?

I th the, the zoo’s conservation program, I mean, it’s been through a number of iterations as as directors have changed and as management has changed, there was a, we had a director of operations that said, you know, his definition was conservation was what went on outside the fence. We didn’t do conservation in here. We ran a zoo. Conservation was what went on out in the field, which is not something that we subscribe to today or that I subscribe to. So we weren’t terribly involved in conservation programs before. There were veterinarians that were here that, that had that, that contributed directly to conservation programs that they were involved in themselves, that weren’t necessarily the zoos program, but we could provide them the, the freedom to pursue that. And, and so we, we went from that stage to the stage where we provided veterinary services to things like Dr. Randy Wells Dolphin research program down in Sarasota, which is run under the auspices of Brookfield Zoo. And, and it is Randy’s study that’s been going on for more than half a century, which is incredible. And we started out offering veterinarians to assist with sample collection analysis and that sort of thing, to the point where the veterinarians, particularly Dr.

Langan, are an integral part of the, the work that that Randy’s doing on the, on the dolphins. Dr. Atkisson, our director, brought programs, I mean, one of the things that was amazing that he as a, as a resident, he developed a program while he was at St. Louis looking at penguins and marine mammals down at Punta San Juan in Peru, particularly built around Humboldt Penguins and essentially started a program in terms of veterinary assessment and disease surveillance in that population, which has grown into a very credible and very productive conservation program. You know, bringing the local population and getting them involved in population of wildlife in that area that they have never had. And, and it was building on a program that, that started with folks out of the WCS decades ago. But that program and that partnership that’s been developed has really taken on a much more significant conservation component under, under Dr. Mike. And now it’s become one of our flagship conservation programs. So the answer to the story is, it, it’s been an evolution and probably compared to, compared to medicine, there’s always been zoo veterinary medicine going on here during my tenure.

And, and that program has grown, expanded in terms of conservation, wildlife conservation.

It went from, you know, the change was much more marked in that it went from, we didn’t have any involvement in it to very substantial integrations of veterinary components in all of the various research progre conservation research programs, programs that we’ve got going on, What should the veterinarian’s role be in animal escapes?

Can you describe some of your experiences, both in Lincoln Park and Brookfield with major escapes?

What management lessons did you take away from ’em?

I think, and I’ll also speak here, one of the things that I’ve done with a ZA is I’ve been a part of and now an advisor to the A ZA safety committee since that committee was created. And animal escapes is a, a key part of that. The biggest role of a veterinarian in animal escapes is prevention exhibit design, you know, and beyond, beyond prevention, beyond trying to understand animal’s capabilities, developing, developing plans for how to effectively deal with animal escapes, particularly dangerous animal escapes. One, one thing that I’ve been a proponent of recently, it’s, and, and this is an experience that I’ve had part of zoo medicine, and it was a much more important part early on in my career, is being able to get drugs into an animal at a distance. We used, we used to use old metal darts that we fired out of a modified BB gun, then we developed into things that we blew out of a blow pipe and other things that were less traumatic and more effective. But part of the things that a zoo veterinarian has to use on a regular basis is e equipment to shoot a dart into an animal to inject antibiotics or whatever, or anesthetics. And one of the, one of the pieces of feedback that I’ve heard on from the safety committee is, well, we want to get our veterinarians to practice for animal escapes, but they go, we don’t need to practice. We use, we use dart guns all the time.

We, we don’t need to practice. We, we know how to load up a dart and, and shoot an animal with it. Problem is when, when you put an animal into a smaller enclosure or a bedroom size enclosure, they’re not very far away. They may be 10 feet away, maybe 15 feet away. And, and if it, you know, if you dart them and it takes ’em 10 minutes or 15 minutes to go to sleep, that’s fine. They’re not going anywhere. However, if it’s an animal that’s running around loose in the zoo, you might be shooting it from five or 10 times the distance that you would in your normal, you know, everyday work. And it can be problematic if it takes 10 plus minutes for the animal to go to sleep. So the message that I’ve been trying to get out there is darting animals with anesthetics to make them go to sleep in your routine veterinary work and an animal escape might be completely different, different drugs, different darts, different dart guns, different dosages.

They’re, they’re really comparing apples and oranges. And so trying to get that message across that we need to, that veterinarians need to understand that they are two different circumstances. The animal’s behavior is completely, you know, an animal in a space. The animal in that’s, that’s in a space that they’re familiar with may be apprehensive that they’re gonna get darted. But an animal that is loose in an environment that they’ve never experienced before may be panicked. And the amount of drug that it would take to make animal A go to sleep may have little to no effect on animal B. So, so anyway, that’s the veterinarian’s role. And my role is to convince veterinarians that a and B are different.

What importance should a veterinarian put on infectious diseases and how they may affect the zoo population?

I, I think, I mean, infectious diseases is a particular interest of mine, more from the standpoint of wildlife and things we call emerging infectious diseases. A great example of an emerging infectious disease that’s in the news on a pretty regular basis is highly pathogenic avian influenza. This is a disease that’s now jumping into mammal species out of birds. It’s having an impact on marine mammals in wild settings. It’s having an impact. It’s gotten into dairy animals, food animals, and also into some people in that regard. So, and it’s, and it’s from birds that are flying overhead. So you need to guard your zoo population as well as the public health and the health of your animal staff.

So infectious diseases is perhaps not as important as it used to be in terms of a direct threat, something that you had to treat on a regular basis. But in terms of being aware of it as an environmental threat and something that can move between people and animals or wildlife and and animals or to zoo animals, it’s critically important. Covid covid had a huge impact, obviously on the global population, but it, it’s had an impact on zoo populations as well. And we have to, particularly during the, the heat of the covid outbreak, we had to manage our animals differently than, than we did previously to prevent humans from spilling over their virus into our zoo animals. And, and we wound up having to be very cognizant of it and had it pop up in parts of our collection that I and many zoo veterinarians weren’t really expecting it. The logical thing would be to have COD attack the things that were most like people. ’cause that’s what we were used to dealing with. That’s where the, that’s where the pandemic was happening.

And, and, and so we were looking at gorillas, chimps, orangs, but instead the animals and the populations that have been mostly impacted are carnivores, big cats, canids. It’s gone through a few zoos as a few zoo gorilla populations, but we haven’t seen it in other great apes. And the extent of the gorilla outbreaks have been less numerically than it has been in the big cats. So live and learn, You become vice president of veterinary services.

How does this promotion come to you?

Well, the, the veterinary services part, and again, I’m can’t remember exactly the, the chain of events, but I think it happened around the time that we changed the name of the department to veterinary services. And, and I think it was a recognition of, you know, I, not necessarily a higher status, but, but recognizing, I think, the importance of veterinary medicine as a program. So it, it’s not, you know, Tom did a wonderful job, this is a slap on the back, but a recognition that, you know, we have people leading animal programs and veterinary services and, and we see those things on a par.

Does your role or responsibilities change in this position Like the day before and the day after the position changed?

Not really, you know, but, but I, I think it’s, you know, if you look at, if you look at what our job was, what our responsibilities were, and then the things that we were accomplishing, I think you’ve got this sort of, you know, steady progression. And then, you know, at some point you say, this is now, this is now bigger than this title, and, and we bump it up to this. So it’s, it’s almost like the difference between a ramp and a stair step in terms of recognizing the growth in, in, in the importance of a particular area. So did it allow you more freedom to shape the veterinary department or No, I, like I say, I, I think it was, I, I think it was more a recognition of what had been done than, you know, certainly not being handed an entirely different slate of responsibilities or additional responsibilities. Throughout your career, you’ve had exposure to many animals and stories during your career.

Can you relate some very specifically, the gorilla with the removable cast?

That was when I was at Lincoln Park. I used to, we used to, I used to host a nutrition meeting and you know, as, as we, as we had those meeting, as those meetings evolved, I chose topics that were of interest to, that I thought was that were important and were of interest to me. And they, they tended to attract a lot of zoo veterinarians. And so we would exchange stories among zoo veterinarians.

And one was, I, I had talked with veterinarian that she called me up and, and asked, have you ever put a cast on an adult gorilla?

And I said, well, I haven’t, but I, I wouldn’t let that stop me.

You know, gorillas have always surprised me with what you can get away with, but what are you, are you are, are you trying to fix a fracture?

’cause I think internal would, she said, no, it has nothing to do with that. It’s, I think it may have been a spider bite. The animal has a big patch of skin that Necros died and we have to do a skin graft and, and you can’t disturb those. It’ll be itchy. So they wanna put a cast over it. And I said, I’d, I’d give it a try. You know, you’re gonna have to go a joint above and a joint below so it can’t slip off. And so I said, yes.

And it was some time later when I ran into her at one of these meetings and, and asked, so what, whatever happened with that?

How did, how did that work? She said, oh, it worked great. We, we put the cast on her. The biggest thing we were worried about was that it would get an infection, a bacterial infection, and we weren’t gonna be able to see it. She wasn’t gonna be able to tell us and it could go bad. So we trained her to come up each morning and get a treat and hold the cast up so we could sniff and, and make sure that nothing bad was going on under there. So she said, we did that worked great. We immobilized her. Every few weeks, changed the cast. And you know, we got to the point where it was sort of a tossup, you know, that the dermatologists were saying, you know, maybe we could get away without it.

Maybe we ought to cover it. And they said, well, let, let’s just, let’s just do it one more time and you know, we won’t have to put the big cast on, we’ll just put a short one on. And they came in the next morning and the gorilla was there, and the cast was laying on the floor a few feet away from her. And when she saw the keepers were there, she, she quick grabbed the cast, put it on the wrong arm, and came over and put it up for them to sniff, because it’s like, I, yeah, I gotta get my treat. So she didn’t know The story of the tomato well, that licked Dr. Wolf Springs. Well, you, you sort of gave the story away. So we were doing a, a reproductive study onus, and what we were looking at was reproductive tract cytology. So we would take a swab of the, of the vulva, of the ua, and, and then look at the cells under microscope.