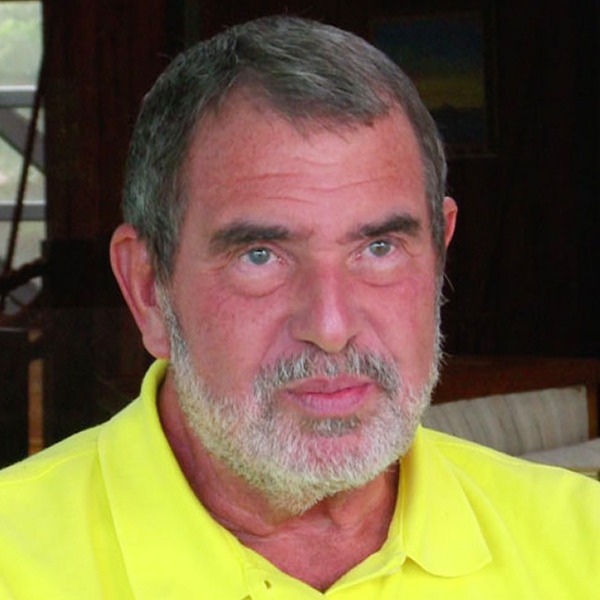

My name is Mike Sulak I was born on December 1st, 1948 at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.

And you grew up in Chicago?

All my life, yes, in the city.

What was your childhood like?

Well, we lived on the west side of Chicago. It was kind of like the traditional fifties Jewish ghetto, had lots of relatives living in the same building. And very close to us, went to public school. Robert Emmet Public School and Austin High School in the city, in the sixties, early sixties, neighborhoods started changing and there was a migration of people into suburbs or different parts of the city, we moved to in my senior year in high school, I can’t think of any other specifics you made.

Where did you move?

Moved out to Lecture Drive on lakefront in Chicago, north side, north.

Which parents?

My mother was homemaker as was typical in the fifties. And my father was in sales at various sales jobs, but he also retired kind of early. He was 55 when he retired for health reasons.

So what’s your earliest memories of zoos?

What zoos?

Well needless to say with Lincoln Park and Brookfield in Chicago. I guess I got my introduction or love, my father loved zoos. I mean, he would go there by himself if he was out on the road and had some time to kill, between calls he and he would take my brother. I didn’t mention earlier that I have an older brother, he on Sundays would be our father son’s day, usually ‘cayse my mother was not a lover of zoos, but he would take us to Lincoln Park or Brookfield commonly. And we would go with our loaves of bread, dry bread because in those days they certainly allowed you to feed the animals. And we really like enjoyed I guess Brookfield more just because the size and the yards where you can throw the bread and see the animals more openly, I guess. I don’t know what the exact word is, but did that. I never remember not doing that.

And were there certain animals at Lincoln Park Zoo or Brookfield Zoo that you really remember or that you were drawn to?

I was always like the mega vertebra. I mean the great apes. At Lincoln, at Brookfield, I forgot the elephant, Ziggy, the elephant was there for years and chained up for years and was always marveled by that. And I remember things that used to as a kid, be fascinated with the glass screens in front of the rhino exhibits at Brookfield because they’d urinate on the public and as a kid, that was something special. So I’ve certainly drawn like I said, to the mammals more so than birds or reptiles, I was fascinated with the reptiles. I never understood. I certainly remember Brookfield closing, I’m sorry, Lincoln park closing the reptile building on feed days, which I always wanted to see as a kid. I don’t remember ever having the opportunity at Brookfield.

I assumed they may have done the same thing, but really don’t remember that. But I remember being mad ’cause I couldn’t see and feed the reptiles at Lincoln Park. Now you said you moved to Lakeshore Drive.

Did you ever bring home, did you have pets as a kid or did you bring home animals?

I loved animals, I mean, there’s a whole history of that. As much as my father and myself loved animals, my mother hated animals. They were dirty things that you weren’t supposed to have in the house. She was a typical Jewish mother. The pets that I was limited to as a kid, I never had a dog or a cat as a child, I had hamsters, I had parakeets, fish. We got into tropical fish, freshwater for many years, but I never had a dog or cat till I moved out of the house. Then I’ve had dogs and cats. I remember even in terms of my love for animals, we lived in this large building in Chicago that had basements and we owned the building and the basements had these storage sheds that each apartment would get a storage shed.

And I remember, there was in one of the back, one of the separate basements, in one of the back basements, I wound up getting some mice and putting the mice and breeding mice in this shed that my parents didn’t know about, for years. Not years, for months and I was breeding mice and selling them to pet shops. And that’s when I was probably 12, somewhere, whereas old enough where I could bicycle with my mice then hamsters to sell them to pet shops.

Well, I have to ask, why did it stop?

They discover it?

Yes, my mother found out about it and that was quickly ended. But then we moved the business. I had another friend in another building who had a similar situation and there was a shed. And then we really started breading hamsters, big time. And we couldn’t produce enough hamsters. This was in the early sixties I guess. And we couldn’t keep up with demand. We had a couple pet shops want 50 or 100 a week.

And you know, we were having hard, we were pressed to be able to come up with the numbers.

So when did you first think about, well, I guess what’d you want to be when you grew up here or when did you first think about, I wanna work in a zoo or did you think of other professions with animals?

It well, it’s strange. And I really don’t know when I made the jump. It was relatively early, when I was a kid in grade school, I had no idea what I wanted to be really, when I first entered high school though, I wanted to be an architect and I started taking drafting classes and stuff like classes that would gear me towards an architectural background. But then I guess my sophomore year or junior, probably my sophomore year, maybe junior, I started thinking I wanted to work with animals and be a vet. I mean, I really thought I wanted to be a vet. Backing up just a little bit prior to high school, I was working at a facility in Cook County called the Thatcher Woods, Little Red Schoolhouse, not working, volunteering on weekends. I’d ride my bike and they’d have a bunch of kids that would service the animals and take care of the animals, that this was, I don’t even know if it still exists. I would hope it still does. There was this woman who was famous in the area named Virginia Mo, Miss Mo and was wonderful with hand rearing animals.

And she had a bunch of animals, she’d be using lactating cats to raise squirrels in the springtime, or it was just a fun, fun, fun place to work. And that was really my first experience, really working with a variety of animals. Like I say, I did that 12, 13, maybe 14, my first job paid working with animals. I worked for a pet shop when I was 16, and they were primarily fish. They had some birds and just mice and hamsters and rats and Guinea pigs, I guess, I did that until I left for school.

So would you go to, you finished high school and you go to attend where?

Southern Illinois University in Carbondale Illinois.

And you were interested in zoology then, or you still interested in architecture?

No, I mean, like I say, I changed my curriculum or in high school, probably my junior year, maybe my sophomore year. I really don’t remember exactly, that I then started out thinking I wanted to be a vet, I mean, there was a time that I wanted to be a pilot, a commercial airline pilot. And I had a lot of battles with my father about that. He didn’t want me to do that for some strange reason, but then I focused in on thinking I wanted to be a vet. And then when I went to Southern, didn’t a vet school, but I was majoring in zoology.

So you were interested in zoology and as you were progressing at the university, were you then thinking about, I want to work in a zoo or when did that kind of come to your mind?

I guess soon as I decided I wanted to work with animals, I wanted to work with zoo animals and I wanted to be a zoo vet, and there may have been impact Lester Fisher on his Arc in the Park. And I was raised with Marlin Perkins and Zoo Parade and Ark in the Park in Chicago and all that stuff, seeing those shows on television were part of my growing up and experiencing, thinking about what would be like working with animals. So you tell your father or your family, I wanna work with animals and I’d like to work in a zoo, you’re attending the university.

What does your father say to you?

And does he say, I’ll get you a job or do you say I wanna work at Lincoln Park?

Well, I mean, I don’t remember any specific questions, you know, questioning me wanting to work at zoo or be a vet. I mean, I’m sure my mother though wasn’t a doctor, a doctor, it was a doctor, a vet, which was probably acceptable to her. And I did, I guess in college, somehow I was doing some research for a summer job and seeing that I wanted to, I didn’t wanna work in zoo. I wanted some hands on experience and found out that at Lincoln Park, the children’s zoo operated seasonally at the time and was open in the summer, maybe early fall, but they close it down during the winter. And during the summer, they would hire six part-time laborers to work in the children’s zoo for the summer. They were college, as I remember, there were always college students, all guys, I don’t remember any women at the time working in the summer as laborers. They did have some other positions, zoo leaders, I think they were called. So luckily my father knew somebody at the park district because this is sixties in Chicago and everything was so political.

It may still be like that, but I’m so far removed from it, but it was totally political in the city. And luckily my father knew somebody who was very influential in the park district, and I was able to get a job at Lincoln Park. It was actually very special in terms that I didn’t get a laborers job. I actually got an animal keeper’s job at Lincoln Park, which was unheard of at the time for multiple reasons, A, it was a summer job and you were supposed to be a laborer. B, I was 17 years old at that time. And you’re supposed to be 18 to be an animal keeper, but I got to be, it went through, I went to Lincoln Park and I was working, they signed me at the farm in the zoo, which I loved. Though I was working with domestic stuff, I just had so much fun there. It was a great first experience with large animals, that were probably a little easier to deal with than with the exotics.

I mean, the difference being that with almost all of them, we went in with, ’cause they were domestics opposed to the exotics, you’re with the exact year removed from many of them. So you started Lincoln park zoo in 1967. Yes.

The general question was, what was the zoo like when you started, what were your impressions of the zoo now that you were kind of on the inside?

And the secondary question is you’re at the farm in the zoo.

What was the work ethic like?

Did you work, because you were the college kid, a little harder, did you find out that people wanted you to do the work or were you all pitching in?

Well, okay, interesting question. Interesting point, Lincoln Park back then in the sixties, the farm and zoo was like, as I remember, I mean, it was the newest thing, it was something very special. Dr. Fisher wanted to build a working Midwest farm in the middle of an urban area to show the people of Chicago. What’s a cow, I mean, because many of them had never left the city and their experience with farm animals, would it either be on television or in books, there’s no videos at the day, there’s no internet. I mean, people wouldn’t know what farm animals were like, the work ethic, I find interesting, when I went there, the keepers were generally long term employees, old, have always worked at Lincoln Park zoo, cared about the animals, would be happy to let me do all the work, if possible, I mean, and I was excited to do it. I mean, to me, it was, this is what I wanted to do. I remember, took me a couple weeks before they allowed me to work in the dairy barn and milk the cows because that was like something special to milk the cows. But I finally got to milk the cows.

I mean, the other thing that I totally enjoyed and it was work, but it was totally recreational. They had a barn of horses and they had about half a dozen horses. And they ranged from Shetland pony to mule, to American saddle bread, to quarter horse to Clydesdale. And there was a small paddock off the barn where the animals would be, where let the horses during the day. But there was also an old rink in Lincoln Park, not the zoo proper, but in the park proper that you could take the horses, where they could run, and everything was broken, where was rideable, even the Clydesdale. And we would wind up taking the horses to the rink, let them run, get on them once in a while and ride them. And then I don’t remember, it was just me asking, they suggesting, there was a riding trail that runs the whole length of Lincoln Park on the lake shore. And at that time, horses came and went.

I mean, it was at a low time for other horses. You know, the barns had closed down. There was no run, but they allowed, I was allowed to take the horses and exercise them and I would wind up going in the afternoons. I’d a two hour ride along Lincoln Park. And here I am in my teens, late teens, riding a horse, I always thought, it was such a wonderful way to meet girls. It was great. They always wanted to come and pet my horse and did that regularly. I mean, I had a colleague that joined me too.

We used to go ride in regularly and I never ever thought of me working at the zoo as a job. I mean, it was fun. It was a hobby. I couldn’t get enough of the zoo.

Did I answer the second question?

What were you, talk about your responsibilities?

Did you ever get to the children’s work or you always stayed at the farm and the zoo. No, that was my first year, when I was an animal keeper. Then the following year, the following couple years when I got the job for the summer, I was a laborer and generally worked at the children’s zoo almost exclusively. I mean, there would be a few times that there would be sick calls in the main zoo and they didn’t have enough people. And I may have had some experience with something. So they moved me out. But that was few and far days between.

What were your responsibilities at the children’s zoo?

It was a bunch, the children’s zoo had a building, which had small animals in small, strange little cages that were very difficult to clean. They weren’t designed to be cleaned. They had primates perched on poles. They had a big pen in the center where they put anything from, could be a baby tapir or a giant anteater to goodies, it was just a huge hodgepodge of animals. There was also a nursery attached to the children’s zoo, which we didn’t have anything to do with, but in those days they were hand rearing a lot of animals. And then there’s the outside area of the children’s zoo that would have, they had a large squirrel monkey cage. They’d have a calf there sometimes. They have or llamas or alpaca.

I remember them trying one year they had, oh, nevermind. I can’t remember, a turtle pool, just in the area to get out where kids could get close, there wasn’t that much contact with them though. The animals were these concrete pits kind of like, almost like the old bears grotto type exhibit, where people could interact with them. And I’d spend the day cleaning. You know, we’d have to get the children zoo clean basically by 10 o’clock. ‘Cause that’s when it opened up, we started at eight. So you also had the opportunity, you ranged around the zoo on your own just to see the place.

What kind of place did you see?

What was the zoo like when you were there?

I mean, certainly when I was there as a student, a kid, just fascinated by animals and also being in the sixties. I mean Lincoln Park was a menagerie of exhibiting animals, showing animals, most of them were in cages. They had a few, the bear exhibits, they were caged in front, open on top. It was still basically unchanged for many, many, many, many years from when they build the large, classical buildings. I mean, Lincoln Park was a compact facility. I think it was 35 acres. And I’m not sure if that included the farm in the zoo or not, but it was a very, in the middle of an urban area, it was very compact. So they were limited in space.

They didn’t have the luxury of real estate, like Brookfield, which was about 200 acres. So it was, the primate house, monkey house. I mean, there was monkey house, lion house, reptile house. They had the basic names as they were for 100 years. The primates were in cages behind, all in cages, but behind glass, the lion house was all the classical, small, giant building where you could be, I don’t know, I’d say eight feet away from a lion, behind bars. And they had the same situation outside. I guess there was something remodeling in the birdhouse about that time, but once again, too, they had the outer edges of the birdhouse was caged birds, birds. And the inside was like a free flight area in the middle.

And there was also, as I remember one towards the back end of the building. And you went to the zoo to see animals. Education wasn’t, as I knew it, as I thought about, if I even thought about it then, it was to go see animals, experience animals, see them, touch them, smell them feed them maybe, it was just to go have a good time. I think of man’s relationship with animals takes back 30 years, thousands of years, and they’ve always had animals as part of their culture, almost any society, whether they served purpose, whether they’re working animals or just companion animals, or feed animals. I mean, animals that they would use for food. I mean, there was always a relationship with animals. And I just think, the zoo was a way of seeing the animals you couldn’t keep in your house.

Did you ever have any concerns for your safety when you were working in this area?

In terms of specific examples, there was a couple times, there were things that we wound up having to do because you you’d be grabbing animals. I mean, just to relate an early story that I always liked to tell when I was working at the zoo, very early on at the lion house, in one of the back cages, and they had these small holding cages, I think we called them hospital cages at the time. I don’t remember exactly, but they had a snow leopard there that needed treatment. And I remember the senior keeper there, Willie Renner was his name. They had to grab, and I think they had to give it a shot or do something. Some way they really had to manhandle the animal. And Willie went in with this hoop net and netted this snow leopard. And that was like the first time I ever saw anything like that, other than what you see on television, zoo parade showing pictures in Africa or something, grabbing animal, I was so wowed by this, that’s the stuff that I wanted to do.

That being said, in my early years experiences that I had working with animals, or that became chancey. The first one was my first summer actually at the farm. And there was one very tough animal there. And they always kept a bull at the farm in the dairy barn, had a pen for a bull. I was working on the dairy side, taking care of the milking cows, cleaning that section. They put two people in the building. One would do the dairy side, one or two. They always had a bull, maybe a pig that was with piglets, and sheep or calves that were being reared.

And I remember he went in, and I don’t know why he went in with the bull or wouldn’t go out. He was trying to shift it. And then while he was in there, the gate closed and he was trapped in the yard. And he just, he panicked. I mean, he was certainly in a dangerous situation. I don’t remember the bull attacking him or anything, but he couldn’t get out. And I came running over there and I was able to open the gate where they could shift the bull. So that was my first experience with something that I had to do, reacting, thinking that I had help someone.

And I remember another year, another time rather, new kid, wanna do anything I could with the animals. We had an old sea lion pool, and in it they had one male sea lion, California sea lions. And they were probably six, seven females. And they all looked the same, and they were having problems with the animals, they weren’t doing well. And they didn’t know who could eat and who couldn’t eat. So Dennis Meritt, who was one of the zoologists there, thought that we should, he wanted to paint, put spray paint, these female sea lions different colors. And when they’re feeding them, they say blue fish, red fish, and be able see who was eating and be able to tell who was eating and who wasn’t. And this was the old original sea lion pool, as far as I know at the zoo.

And it was just, it was a donut, it was a giant pool, inside, in the center, there was this rock island. And underneath the island, there was this tunnel that measured, I don’t know, three and a half feet by three and a half or four by four, that just went through the exhibit. And whenever they wound up having to clean the pool, drain the pool to clean it, drain it. And when the keepers went and start cleaning it, all the animals would run into this tunnel and just stay there while they’re cleaning the pool. Well, the animals reacted. We dropped the pool, ’cause we were gonna spray paint them. And they all ran in. And what we were doing is going in from one end, chasing them out.

And as an animal comes out, they’d net it, spray paint it and release it. And then we just keep it out until we had, we needed all the animals painted except for the male and the last female. So then they’d be able to identify all the animals, makes sense. So there was a half a dozen keepers working on this ’cause you needed people keeping the animals, so they couldn’t go back in the island. You need people grabbing them. And we had a bunch of people there and they kept chasing them out and grabbing them and chasing them out and grabbing them. And it was down to the last two, the last one, excuse me, the last one that we really had to paint. And it was like, who didn’t do it, who didn’t go in there yet to chase them out.

And what you would do is you’d go in there with a shovel and you’d start yelling and banging on the walls and hope, plan to push them out the other way. So low and behold, I was the last one who hadn’t done it and they go, okay kid, it’s your turn. So I went in there and he had the shovel, I bent over and it’s all full of algae, it’s slippery. You’re afraid you’re gonna fall. You’re screaming, you’re banging this shovel, hoping the animals were gonna go. And these last two animals didn’t wanna go, to me it felt like I was in there five minutes. It’s probably 30 seconds, I mean, you have to be realistic about it, and I’m banging and screaming and I’m horrified. And then I figured, it’s not gonna happen.

And I’m just backing out. When I moved out, one of them ran, finally ran out and they got it and they painted the animals.

Was I in a dangerous situation?

I don’t know, I guess potentially, I mean, I was certainly horrified at the time doing it, in retrospect, the project wasn’t that useful because a week later, the paint was gone, so they were back to square one. But yeah, it was fun. I loved the thought of doing it. You know, now I think about it, scared at the time, but wanted to do it because I wanted that hands on experience with animals. So you were gaining experience in the beginning.

Did this change or did this alter or cement your notion of what a zoo would be like, ’cause now you’re on the inside doing things?

Was it everything you thought it would be or did you think differently?

It was everything I thought it would be and more. And I mean, but I was limited. I just wanted to work with animals. I wanted to take care of animals. I wanted to feed them, I wanted to clean them. I wanted to see them reproduce and have offspring. And I wasn’t thinking. I could have been an animal kid for all my life.

And at the time I was just happy, I was doing my dream. I was working in a zoo. You mentioned, Dennis Mayor was zoologist.

Who was the director at the time?

And how much interaction did you have with the director or any of the senior staff?

In the five summers, years that I worked at the zoo, I mean, Dr. Fisher was the director. Dr. Fisher was a special person in Chicago. Everybody knew Dr. Fisher, Dr. Fisher would say hello to anybody and everybody. And talk to everybody, he’d walk around zoo commonly. I remember, I mean, even working in the lion house, the lion house, when the office was closed, was like zoo central. The phone would ring, off calls were directed to the lion house. It was just zoo central. And you know, I remember being in the lion house kitchen and the phone would ring and Dr. Fisher would just answer the phone.

Hello, Dr. Fisher, and answer any question that would come on. I mean, he worked so well with the public and the staff, as I knew him. I mean, here I am a kid zookeeper, laborer, probably was scared when he came by, he was the director of the zoo.

What am I supposed to say or do?

And he was just a nice guy. And you would just, you would have these conversations with him. I was more probably, I mean, certainly early on, more petrified and fearful of the conversations than I was later on.

Did you have experience with other members of I guess I would call them the senior staff?

Yes, I actually became quite friendly with one of the zoologists, Mark Rosenthal. I didn’t know initially, we started at the zoo at the same time, when we started in 67, as I said earlier, I was working at the farm and he was working at the children’s zoo, but we kind of heard, we went to the same school. We went to Southern Illinois University, but we didn’t really meet till the end of the year. Close to the end of the year before we actually met and then, found out we both wanted the zoo careers. Mark was a couple years ahead of me and we became very close. I mean, to this day, we’re very close. Dennis Meritt was a zoologist. He ultimately became the assistant director of the zoo and Saul Kitchener, who was a curator and Dennis became curator.

I mean, there was all kinds of changes there. I became very friendly with all of them. And God bless Saul, he was my mentor, my friend, and invited me, offered me a job in San Francisco many years later, Lincoln Park at the time seemed like a very special place because the staff got along so well. I mean, they were friends, they traveled together. It was a learning process for all of them. I mean, Saul certainly had the most zoo experience prior to Lincoln Park, Mark and Dennis were relative newbies to the zoo business. There was also a curator, I don’t remember how the titles were in birds, I was not a bird person. And then there was Eddie Almandarz, who was the curator of reptiles.

Zoologist and curator, reptiles, I guess. Eddie grew up in the zoo, and I probably had 25 or 30 years experience, in the sixties when I’m talking about it, all of them helped me in terms of mentoring, about stuff at the zoo. I did at one point in time, it surprised me. They assigned me at one point to the reptile house and I wasn’t a reptile man, but I wanted to do it because once again, I wanted to learn all aspects of the zoo business. So you’re attending Southern Illinois University. You’re thinking about a zoo career.

What was your plan?

You worked at the zoo summers.

Did you have an idea of this career path after that?

I wanted to major in zoology, I wanted to go onto vet school. I saw that wasn’t going to happen because the curriculum that they had for vet school required more chemistry than I had the ability to pass. So I was just happy to stay in zoology and I wanted just to get a job at the zoo. I knew I wasn’t gonna be a veterinarian. I just wanted to work in the zoo.

And what did you think about doing this full time now?

How did you think you were gonna get into the profession full time?

How did that occur?

Well, once again, getting into Lincoln Park, I had the advantage of getting these jobs politically, but I also knew at the time, and I still say this today if anyone asks me about it, I mean, it’s important to get your foot into the door, volunteer at a zoo, get a job at the zoo. Once you’re there and your foot in the door, you have your chance to establish yourself there. And beyond, if you don’t have on your resume zoo experience, it’s such a small field and there’s so many people that think they wanna work in the zoo. I mean, people start working in the zoos and find out it’s not what they want it to be. I knew just the importance of me working at the zoo, yeah, at the time, I guess I would’ve been happy if I stayed all my life as an animal keeper at Lincoln Park, I was doing what I want to, course changed. And things happened that shortly after and happened probably sooner than it should have. In 1971, I was working at Lincoln Park as an animal keeper. And then I literally was offered a job at Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville as a zoologist, I literally didn’t apply for it, Saul or Dennis talked to John Zara, who was a director, and I guess they were looking for somebody and they suggested me.

And I talked to John, this was probably, I started working there in June of 1972. And in September, I was offered a job as a zoologist at the Mesker Park Zoo. And then I started thinking, career choices. I mean, and it literally, it was a smaller zoo in a smaller community. And I even wound up taking the $2,000 pay cut to become curatorial staff or administrative staff at a zoo. And here I am working full-time at Lincoln Park, living with a couple of my friends from school, having a great time, great time in the day, working in the zoo, partying at night because we had the money to do it.

And what was my responsibilities?

And then here I get offered this job.

They’re going, I have to move, take a pay cut, go to a smaller city, do I want to do it?

And it didn’t take me long to make that decision because I did do it because once again, knowing the field was so small, how often do you get an opportunity like this?

So I then went to Evansville as a zoologist.

When you went to Evansville under the director, what kind of zoo did you find and what was it like when you first got there?

Evansville is located in Southern, the most Southern extreme point of Indiana. It was at the time, the largest zoo in Indiana. I mean, since then other zoos have grown, Indianapolis became a pretty big zoo, is a big zoo. It was a small zoo that had, excuse me, basic collection. I mean, they had a little of everything. There were two buildings at the zoo. There was one building called the clay building. And that had the bird collection, small mammal collection and downstairs, they had exhibits, they had a pair of hippos.

They kept tapir in another exhibit and they had one elephant and that building was built in 55, and I went there in 72. They also had an older building called the old building actually, connect building. And it housed the cats. They had leopards and tigers and primates in that building. They had a couple chimps were the only apes they wound up, they had some Gibbons to actually, you wanna consider them apes. And then outside the grounds was very, it was like, almost at the outside limits of the city, excuse me. They had primarily large pens with hoofstock. They also had a one grotto motive exhibit where they had lions and nothing spectacular in terms of the collections.

It was a small collection. They also had a sea lion pool, which shortly after I came, we stopped using, it became just deficient. I mean, it was just falling apart. The city didn’t fund the zoo very well, small zoo, but it met the community’s needs.

So who were you working with?

I mean, what was the structure of the zoo?

Okay, so the zoo was city owned and operated and we came the park’s department. The staff at the zoo consisted of the zoo director. There was a general, excuse me, general curator. And the zoologist. When I was hired at the zoo, John hired me, the general curator had left. John hired me as zoologist, and he told me that there were two zoologists, one of them at some point in time, he will promote to general curator. He has to decide who would better fit. I think he had his own plan in mind at the time.

I mean, things did change. So I went there as a zoologist. And we would be responsible for running, just taking care of the zoo day to day. And on weekends, we worked the same days actually. And John would be covering the zoo. John would be covering the zoo our days off during the midweek. Shortly after I left, the other zoologist, who was just, that wasn’t his career. He took the job.

He was there before me, I guess he volunteered at the zoo, and then he was offered the position and he took it, but he left shortly after that. And then John hired a gentleman named Frank Kish, who was a zoo person, who worked, was a known bird person at the time. And he hired Frank as the other zoologist. And literally, I guess I was there about 10 months. Frank had only been there three, four, maybe five months. I don’t remember exactly how long it is. I mean, one day literally John said, Mike, I’m making you the curator, which just blew me away. And I was thrilled with, so once again, I mean, it came down to, there was three zoo administrators, there was a maintenance foreman and that was the administrative staff at the zoo.

And the zoo consisted of, I think it was 18 keepers and one dietician who was just, was not a licensed or trained dietician, who was an older lady that had worked there, that would repair the diets. Every Monday to Friday and then would have one of the keepers relieve her on the weekends and a four man maintenance crew. And that made up the zoo. We did have seasonal cashiers ’cause the zoo charged admission six months a year and six months was free. Give me a typical day in the life of a zoologist, early in the morning till late at night. As I remember it, I mean, John was really good. John, you did what John said. I mean, and it was his zoo, and he made all the collection decisions.

He would be making all the deals and basically we were there to carry out his wishes. I think it’s good to this day. I wish I had kept it up, I certainly didn’t do it. But first thing in the morning was a round. You always made a morning round and you would look at almost every animal. I mean, sometimes you couldn’t see some of the stuff in the yard, but you’d get a feel of what the zoo looked like. What needed be done. Let me back this up one minute, prior to our round, we had daily keepers reports and it was a very simple, literally a half sheet of paper lined, where the keepers from the night before would leave a report if they needed maintenance or if they noticed anything with the animals that wasn’t really important, that they’d contact us, during the day to come see you as something.

Oh, I noticed whatever about an animal and be on that report. So you’d go through those keepers reports before you’d make your round. So you’d knew if you had to see, take a special peak at something, not necessarily animal, it could be building, it could be a hose that’s broken. I mean garbage cans that were damaged.

It could have been anything, excuse me, you walked the zoom during the day, what would you do?

You would also wind up sometimes having to work as a keeper. Sick calls, I mean, I wanna say 18 keepers, something like that. we didn’t have too many days when there were extra people. So one or two sick calls could come and just like any other zoo, you may wind up splitting a work area string or sometimes you wound up having to work it yourself. I also, there was, I always, from the almost the day I came there, I became responsible for the records at the zoo. And at first, when I first got there, ISIS hadn’t even started when I first in 72.

ISIS is?

international Species Inventory System. It was the first national, became international, record system, computer record system for zoo animals. I mean, prior to that, we had index cards with the animals’ records on it. I mean it literally would be an index card with what it was on it, who we purchased it from. If we had our birth date, how old it was, I mean, basic information, and then we would add, comments to it, gave birth on such and such a date or died. I can’t say every was done every on every animal in those days, at Evansville, we had a consulting veterinarian and he was in theory, supposed to come out to the zoo for half a day, one day a week when we needed something. I mean, he would come out for emergencies if he needed it. And more often than not, he would tell us what to do over the phone.

And we had a small room that we would keep for our hospital purposes. Would keep the medications and drugs, but in those days, and at that place, it was so small. You wound up having to do everything. I mean, there was one, it only happened one day that I had to act as a cashier for a couple hours, ’cause they were so short and they couldn’t get, cashier called in sick. And I had to go open the gate and sit there and be a cashier. So it was a matter of doing anything and everything. And I don’t know if I’ve been specific enough, you never knew what your day was. And I think that’s typical of any zoo, of any curator.

You may have plans, but the collection or facility can quickly change those plans.

You mentioned that you made rounds, important to you important to do that kind of thing?

I think it’s really important to do that thing. I think A, it gives you a time to look and reflect at the collection, interact with employees and keepers. I mean, as time goes by and as facilities change and whatnot, you may become more distant from the keepers. And it’s important to know your keepers because one keeper could say, oh, this is a problem. And we gotta do something now because the animal’s gonna die instantly. But you know, the keeper is the sky is falling keeper opposed to another keeper. If he says, Mike, we got a problem here. You know who this person is and you know there’s a problem and you gotta do something about it.

So it’s a chance, like I say, to look at the collection, enjoy the collection, interact with people, look at the facility. And once again at Lincoln Park, we had to direct the maintenance crew. ‘Cause the maintenance crew was also the ground keeping crew. And there are probably almost 50% of their work was ground keeping, whether it be cutting grass, getting leaves, emptying garbage cans. We had to take care of the facility. If we had major repairs, we would use the recreation department’s maintenance, or have to call private contractors to make repairs. But we tried, needless to say, we tried to do everything ourself because money wasn’t flowing. So you’re the boss of all the animal keepers now.

General curator.

And how did you have any idea, you’re still young, do you have any management style?

I guess it was kind of still the old school training of zoo back in the 70s, where I didn’t have formal training in terms of management. Certainly way in the future, I mean there were classes, the city of San Francisco offered stuff in terms of taking classes. I went to AZA’s management school that certainly has evolved tremendously over the over 30 years or 40 years that it’s in business. I guess I was kind of maybe in your face type thing, I didn’t want to dilly dally around. And when I wanted something done, I wanted something done, at Evansville, you were dealing with an uneducated keeper that had been there for years and wanted to be animal keepers, but they also would have a farm mentality, I think with most of the animals in terms of their care and wellbeing.

Were you able as a zoologist or a curator to make recommendations, you’re in the collection now, to the director to say, we should do this, we should change this, and how did he take it?

Well, I mean, John would, you have different relationships with different people, but different directors, with different curators and you John how he became the zoo director. I mean, he was the general curator and was promoted when Frank Thompson was the director of the zoo left. And it was, they both I think went to the school of Hard Knocks for the zoo training, and had been in the profession for years and just had their own styles of dealing with things. John was a director and you knew he was the director. And I was still very green initially in terms of what I knew about animals. I was working part-time as an animal keeper at Lincoln Park or full time for a very short period of time. And all of a sudden here I am a manager, a zoologist and a couple months later, I’m a general curator at the zoo, I’m number two. I mean, I had oodles to learn, which I couldn’t learn enough about, whether it be going to conferences.

I went to as many regional conferences as he had allowed me to go. I wasn’t allowed to go to national conferences when John was there initially because he went to national conferences and we were too small. I mean too small to have two people going at the same time, generally speaking, initially, and then just had to be there to take care of the ship so to speak.

Just a quickie on conferences, did you find conferences beneficial to your professional growth?

I thought it was tremendously tremendous. So important, one of the most important things you could do. A, networking, though we didn’t call it networking in the seventies, meeting people, learning who they are, learning who you are, what kind of person you are, the papers that were given, learning about how different institutions were taking care of animals. I guess I kind of grew up as a transition. You hear stories about in the good old days, prior to the sixties, that zoos weren’t real big on sharing information, animals were retainable as long as you had the money to do it. You know, there was very few wildlife laws that prevented you from acquiring almost anything that you wanted. If you can afford it, there was an animal dealer that could acquire almost anything for you. And zoos were not, it’d be interesting to see how many breeding loans there would’ve been for zoos of the early sixties or prior to that, if a zoo was successful with something, it was not uncommon for them not to share how they were successful, what the facility was.

I mean, you could see the facility, but the diet or whatnot, how they were maintaining what they were giving the animal that they were successful with, and I say successful is, I want to say in the beginning, in the sixties, I would think that you were successful with the species if you could bring an animal in from the wild, successfully maintain that animal, have that animal reproduce, raise that offspring and have the offspring breed offspring. In my mind in those days, that made you successful with the species, but zoos didn’t want, some zoos didn’t wanna do it. They wanted to be the only ones that could breed this or get that. So, certainly the seventies, zoos became, they would be sharing, I mean, papers really were important what were given, what different facilities, different people were doing with different animals and the moving of animals became more freer. I think it was also limited to, as the laws changed, endangered species act went into effect in 1972, as I remember, and that certainly had impact. I mean, there were other laws, the Lacey act and stuff that was on the books for years that had had impact on animals, but zoos became more sharing. And as the world changed, what technology changed, whether it be television, video, everything, you know, the world was constantly getting smaller and smaller and smaller.

You mentioned the director, John Zara, when you were there, had more of a directorial management style, did you know Frank Thompson or did you hear things?

Did you feel from either what you heard or knew that there was a different type of style?

Well, I mean you to hear John, John thought of himself as a teddy bear and Frank Thompson was the director. So I knew Frank in terms of talking to him, I started talking to him more for advice after John left, less than a year after I arrived. And there was a period where there wasn’t a director, or I was the acting director, and Frank, who had become an animal dealer. I mean, he was very forthright in calling and offering me help, or I would call him, more so, he was familiar with the facility and that certainly had some impact or a lot of impact. Maybe some of my questions, they may have been facility specific and also animal specific for that matter. I did talk to him for quite a bit during my period where we didn’t have the full-time director, permanent director. And we’ll talk about that in more depth, quick question about the elephants.

You didn’t have any real elephant experience when you came to Mesker Park Zoo, but how did that evolve with the elephant or elephants that were there and what kind of exhibit was it?

Well the elephants was elephant. They had one elephant that they acquired as a young Asian elephant. When the building opened in 1955, she lived in a stall, I’m guessing was probably 30 by 25 in the building. And then there was this large, I mean, large by standards in the seventies, not large by standards today for elephants, there was a circular yard and inside the center of the yard, there was a pool. You could fill it up and have a pool for her. She was probably one of the best or docile elephants in the country. I mean, I don’t know exactly, I don’t remember. She was trained, they had one keeper was with her for years.

And she was trained. She would respond to verbal commands easily. She was very docile. I mean, I worked with her. I became like the elephant hoof trimmer by default. Maybe, I don’t know. It wasn’t something that I relished doing, I would working with the elephant she responded to me too, I mean, through no planned action by myself, she was just such a good animal. I remember we used to wind up chaining her every night.

That was a routine, which was common in zoos at the time. And we also, she was scared of thunder. And when there was a thunderstorm, which was pretty regular in event, we would chain her up. The chains, I mean, we used to say was a security product. I don’t know, I mean, it certainly was done, but it was interesting that there was, lights, and the bars in front of her exhibit inside were just steel bars that were probably about 16 inches wide. And then there were cross members about every 16 inches that went up to about six feet. And then it just went steel up to the top. And I don’t know, you never think of things.

There was a light, there was a door in front of the exhibit and this was the keeper area. It was about eight foot. And then about six foot wide. And then there’s little safety barrier to keep the public out. Or it was just open space. And there was a light switch right there that turned on the lights. So she was playing with the light. She started playing with the light switch.

And so we had enough sense on, okay, we’ll put a plate over this light switch and not use this. But we used to call bunny the educated elephant, this door, she would open this keep door, which wasn’t locked with her trunk. And there was another light switch and the inside could operate the same lights. And I don’t know exactly. I don’t remember exactly what happened, but she was playing with the light switch one time and she got an electric shock. Something happened. And when she backed up, she had small, she was an it Asian elephant. She had about 12 inch.

Probably about it’s eight inch tusks. And when she got the electric shock, she backed off and she broke off part one tusk. it was just split. And we knew we had to do something about it and we didn’t know how well she would do it. But once again, being the great elephant she was, we laid her down and I took a saw and I just saw it off. The keeper was there with a Angus, holding her trunk down and I just sawed off the tusk And I also took off the other one, so she would look balanced, but yeah, I was so naive. I didn’t realize how dangerous it potentially was at the time. Me still being, I guess you’re always green, ’cause the day you say you can’t learn something, you’ve got big problems, you should be moving on.

You talked about your relationship with the elephant and handling the elephant. You talked about netting, some of the skills like netting skills, some people would say are eroding because fewer animals have to be handled in that way. And there’s more training techniques and so forth, positive, negative.

What is your feelings about the handling?

Well, once again, the business has evolved over thousands of years. But in my tenure it certainly has evolved, the things that were available or known in the seventies to me were still many of the old school ways. I mean, we didn’t have the darts that are available today. We didn’t have the drugs that were available today. We had the techniques that were available at the end, at that point in time, and we had to regularly grab animals. And I certainly, at that time was learning many skills, I’m talking general curator because I was at zoologist there for such shorter period of time. All of a sudden, here I am a general curator, but I still learned from some of the older keepers there how to do stuff. It was still a learning process for me at Evansville.

I mean, certainly the first five years I was there. I mean, at some point in time, I mean, I really had to embrace the role because we wound up hiring more staff in the late seventies due to the federal government making funds available. So all of a sudden we were hiring curators and more keepers and more staff and the curators that were hiring, some were interested in the field. Some had zoo backgrounds, but never worked in the zoo, but none of them that I could remember ever had any prior zoo experience. So there the training would be, online training, you have to go grab, come here, I’ll show you how we grab. I’ll show you how we grab a kangaroo. I’ll show you how we sex a kangaroo. I’ll show you how we’re grabbing hoofstock, you know, deer or whatever.

And I’m thinking retrospectively, in San Francisco, at times we would have training stuff in terms of how we grabbing animals. I never remember doing that in Evansville. I mean, other than bringing the people with, whether it be curator and keepers, who didn’t have that experience that needed to see how something is done. No one likes to see an animal escape because of potential danger and so forth.

And in Mesker Park, when you were there as general curator or zoologist, did you have experience with animals getting out and what was your role and how was it handled?

I think of two instances specifically at Mesker while I was there. One was, we had two older chimps, female chimps that were in this old building That was probably 50 years old at the time. And one Saturday morning, I mean, literally it had like a half moon shaped window with bars on it. And I don’t know if it fell out or they pushed it out, but the chimps got out out of the building onto the grounds. And it was quite quite the day. They immediately left the building and there was some, and we were right next to a main road behind a fence. And there were some very, very tall trees that the chimps immediately went up to. And we’re trying to figure out what to do.

I mean, this is something that you should plan for, but then again, there’s almost so much planning you can wind up doing, because the chimps are 60 or 70 feet or 80 feet up a tree, there’s not much you that you could do with the capture equipment that we had at the time, we immediately called the police in the fire department. ‘Cause we wanted help. We thought maybe a snorkel, we wanted to get ourselves higher because we were trying to dart the animal. First we were trying to coax some down, which was a joke. Just come down closer, that was a joke. But we knew we had to dart the animals, but they were so high up in the tree, when we would shoot, the darts wouldn’t be able to go high enough in the trees to hit them. So we were calling for help, outside help with ladders, or like I say, cherry pickers so we can get up and closer to them. This was literally an all day affair.

I mean, excuse me. It even, on the table at the time, though it was in the summer and there was lots of daylight left, we started discussing, if we don’t get these animals by such and such a time, we’re gonna have to put them down because we it’s pitch black out there. It wasn’t light. We can’t just sit here all night with these two chimps up in these trees. So eventually, the chimps came down a little bit and threw a cherry picker. We were able to get a couple shots off and we wound up hitting them. And then they came falling down through the trees. I mean, I don’t know if it’s good or bad.

I mean, the branches were breaking the fall. We got, actually I stand corrected, we got one earlier that we were able to get a shot of. The second one was later in the one we were worried about and it came falling through the trees. We were able to get our hands on him. I mean, we lost one that day, didn’t survive, the other one survived, and we wound up, it initially survived and then it to passed and it was a traumatic experience for the zoo. At that time we decided, we’re never gonna have an ape there at the zoo again with the facilities that we had. That was certainly a growing experience for me and seeing how unprepared you could be, and even, to do it over again, 20 years later, you have it chimp 80 feet up a tree. I mean, and trees all around it where you really can’t get equipment close to it.

How do you deal with it?

But it is what it is or was what it was. And the other incident that I remember that I personally dealt with, that we had a polar bear at the exhibit, at the zoo. There were like three cages inside, small cages that would bring him in at night. And there was a moated exhibit with a small pool that we would leave out, that would be out during the day. And I remember. The keeper somehow made a mistake where he realized that he opened the door from the outside exhibit to the inside exhibit and the door was wide open to the inside exhibit to get into the keeper workspace was the door open. And he saw the polar bear look into the cage indoor holding. And he just saw the animal and he ran out and he called for help.

And I always think this was my moment of stupidity in terms of what I wound up doing, become running over there, driving up with the golf cart. And I guess we made a call. I don’t remember if we made a call to the police, and to be honest with you, I don’t even remember what guns we had at the zoo at the time. And certainly we had no, I mean, this was a shortcoming. We weren’t practicing on a range or using the guns in irregularity or even, like I said, I don’t remember ever cleaning the gun there. So we called the police. But in any event, I come there and the bear was in the exhibit at the time, went back out, didn’t come in, didn’t walk in. I wanted to, probably the first thing to do would’ve been just close the door to the exhibit where the bear would’ve been contained either in the keeper space, have access to his holding or the exhibit, but me more reacting than thinking it up.

I figured I gotta go in there and close some doors. And I just went in there screaming, making as much noise as I can. I wanted that bear to know I was coming in there and hopefully that would work to my benefit. And I ran in, the bear wasn’t in, I never was face to face with this bear, slammed the door closed to the cage. And that was the end of it. I mean, the bear never left the exhibit, you know, but it had huge potential. Your heart was pounding. I would imagine so, it’s one of those things.

You do something you don’t realize after you’re done.

What did I just do or why did I do that?

But, you know, I mean, I’m sure it’s happened to many zoo people. You just react to a situation hopefully it works out well and there’s no problem.

We’re gonna talk a little about your evolution to general curator, but how do you see your evolution from the zoologist to general curator?

How did that kind of evolve?

How do you see it?

There was no evolution that I guess you can call it evolution or enlightening?

I was so lucky to being at the right place at the right time at that point in my career, I applied for neither one, for neither the zoologist job or the general curator’s job. I mean, literally they were handed to me. I mean, I wanna say that John felt that I was qualified, or could become qualified. I would think would be a better thought, than anything else. Though we talked through the recommendation of Saul and Dennis and me interviewing with him. And he offered me the position. Though, I knew, he said initially when I was hired that one of us would become general curator because the staff is one of each, a director, a curator and zoologist, that one of us would become it, though there was a change because the first zoologist who was there when I hired, had left. And he had hired Frank Kish.

I still, I guess, my thinking at the time that Frank would’ve gotten the job, ’cause he had oodles more experience than me. But when it came literally overnight, he tells me, Mike you’re the general curator. I mean, and he said that he had concerns about Frank, that his animal experience was one thing, but his other skills he had, or mine were better than his, let’s just say, he thought mine were better than his. He could shape me. I’m sure that was helped in his thinking that since I was so early in my career in the learning process, that he could help shape me into being the general curator that he wanted me to be. I mean, but that evolution quickly changed too because literally shortly after he promoted me, he left the zoo himself.

Are we talking about months, weeks?

Months, I mean, it’s probably within six months, I don’t remember exact timing. I mean very quickly that all of a sudden, actually now that I think about it, I was probably at the zoo about a year because he left, I came there in the fall of 71 and then in the fall of 72, he left and all of a sudden I was the acting director of the zoo.

When he made your general curator, at the time, did your relationship change?

Yes, I think we talked about it earlier. It’s one thing knowing somebody and socializing with someone and then working for them, you may get a different opinion. I think he mellowed more when he promoted me ’cause I don’t remember too often. I’d be invited over on a Friday afternoon to his house and we’d have some drinks in the barbecue and just talk. And I don’t remember Frank coming as often. I was there more often, I think. So there was a bit of a personal relationship outside of the business than previously. But once again, all of this is in a very short period of time because within a year and me being 22 years old, I went there, I was 21.

I probably became general curator when I was 22. And later that year, I’m acting director at 22 years of age. I mean I’m sure there’s other zoo directors have started that way, not that I became a director, but I was still a kid.

Was Frank jealous?

No, I don’t think so. It was hard to tell with Frank. Yeah, he was, I mean a great guy and new birds like nobody’s business, old school type thing. I mean handling stuff. I mean he could go and grab anything with feathers and make it look easy. But Frank was also, he immigrated to the United States during the Hungarian Revolution in the fifties. And I’m not saying this detrimentally, he had a European attitude. I mean just how things were and you know, certainly to a small degree language maybe had some impact, and he was also not the most positive person.

I mean, his cup was half empty all the time.

How did the staff, the general keeper staff react to you becoming the new general curator?

I’m sure what they said behind my back and what they said to my face were 180 degrees different. I mean, and some of them, I got very close with and very tight with, some of them, I wasn’t their fan. I became more removed from the keeper staff, shortly after that, I was just a placeholder to keep the zoo together till they hired a zoo director. I had no interest in the position. I made that clear to the city at the time that I didn’t want it, I didn’t have the experience to do it. I didn’t know that stuff. So after a six month period, they hired Dion Albach as director. He was originally from Lincoln Park.

He had been the director at the Providence Rhode Island Zoo before he came to Evansville, became my new boss, became very friendly with him, close with his family. I remember his wife used to refer to me as her adopted son. I mean, and I would commonly go over there. And during that time, a couple years into the time, I mean the zoo changed drastically, probably about into 75. When the federal government created the SEEDA program, I think it’s comprehensive employment training act, and there was a recession going on. And so the federal government put all kinds of money into city, state government for doing projects. And you Evansville must have gotten millions. I really don’t know how much it is, but we practically doubled our staff with SEEDA a in terms of employing additional keepers.

We created additional, we changed the title 10 from zoologist to curators. I mean, we wound up having a curator of mammals, a curator of birds, a curator of education. I mean, we just did wonders in how the zoo grew. We also wound up expanding the zoo, which was the first time in many, many years that anything really new was built. We built a children’s contact area and some new hoofstock areas because of SEEDA monies. Because it literally paid for all the people, not for the materials. And that’s the cheap end of stuff. So we’re able to do lots of stuff.

Okay, let me back up, just so I understand the timeline, from the time you became general curator to the time the director left is a period of how many months?

Six or less. Okay. And then you find yourself in the position that you are in charge of the zoo. Yes. And you decided right away that this was not what you were interested in. Directorship, absolutely.

Because?

I lacked the experience. I didn’t think, if you add up all my, excuse me, all my experience at that time, three months, I didn’t have maybe for three or four years total experience in working at a zoo. But yet you were in the position now as director, whether it was interim or not. And so other responsibilities were thrust upon you, you just didn’t supervise and that was it.

Were you feeling more confident as you were going along or were you totally overwhelmed?

I was, I think totally overwhelmed. I realized, and I remember the dates because it was at the end of the year, shortly after, almost immediately after I took the position, I was reviewing the budget and saw what the spending levels were, that we were gonna run out of money Probably in November. I mean, we had been spending at such rate, and I made the city aware of that, the recreation park department aware of that, which they were, I don’t know why. I don’t know the accounting at the time in many of these things, like I say were thrust upon me, something that I never looked at all of a sudden, I’m looking at at monthly spreadsheets at the time that we were running out of money and that we wound up having to make corrections. And then the parks department had to redirect some money to us. And I won’t say I became a hero.

It was noted that, you know, how come I’m the kid here for a month?

And I just noticed that we’re running outta money, but the previous administration didn’t. And I mean, I certainly could understand. John was leaving the zoo, and he gave notice and looking for the job and maybe he wasn’t 100% into it. I mean, and maybe that was an annual at the time, many places at the end, the year you find out your spending levels, they’re above what they should be for what you were budgeted. I always found, budget in zoos general were amazing. Almost like you have bones and stuff that come up with numbers, I mean to this day, I don’t understand the budgeting process. But you were doing the job.

Did you have a vision for the zoo, if I could be director, I could do this and this I’d like to do it, or you’ve never had the thought?

I was just living from one day to the next, I just wanted to do as well as I could, but I wanted someone there with more experience than me that could teach me what all that, that I needed to know. I mean, certainly, the amount of paperwork. The amount of paperwork that was required then was a lot more than it is today. I just wanted to, every day I wanted to get through every day, I believe that was my goal at the time.

What were your responsibilities in supervision during this time?

Did they change from when you were a zoologist, again, as general curator or?

Well, at that time, we were still just a small zoo, you know, had the small staff. This was prior to 75 when the SEEDA monies came in. So during that time it was Frank and myself running the zoo and the labor, I mean the maintenance foreman and this was it. And I then wound up changing my days to Saturday and Sundays off because suddenly, I was spending an in ordinate amount of time going downtown to city for meetings that I had to do, that came with the position. But also when we were going through this budgeting process of figuring out what happened to the end of the year. I was a caretaker.

I mean, I was a caretaker director, was I learning stuff?

Sure, I learned a lot of stuff, you know, the business end and working with downtown. I mean, I may have gone occasionally to a meeting only very few and far between, but suddenly I’m going to the monthly park board meeting, I’m meeting personalities, I’m meeting politicians. And just as important as the black and white spreadsheet, dollars and cents things, it becomes very important to be able to work with people. And sometimes that’s more important than anything else if you could go and you get that slap on the back and how are you Mike, and what’s happening, opposed to, works wonders.

Aside from the budget, were there other problems that existed at Mesker Park that upon your interim, you started to notice or were aware of?

Yeah, it was an old, neglected facility. There was always problems, physical problems. I remember the clay building, which was the main building that had the bird, small mammals and hippo, that building, which was built in 55, had a boiler that was constantly going down. I mean, the money that we wound up spending trying to keep it going. And finally, and I don’t remember exactly when, they did replace the boiler. I mean, I’m looking when you talk about problems, it’s the physical plant was falling apart and neglected, after the fact, as we talked about earlier the window on the chimp cage, literally I’m assuming fell out. I mean, if they shook it, it from years of shook it and finally wore it down, I can’t say is thinking about that location. You inspect things when the last time anyone went and shook the bars to see how secure or what was going on with that.

So much of this, the work that was done was 30 and 40 years old at the time, I don’t remember animals as being a problem. ’cause the stuff that was bad, like as I mentioned earlier, the sea lion bowl was a horrible thing that was closed. We had it open initially when I went there, but it was quickly closed because it was just a maintenance nightmare that we didn’t have the funds to bring it up to par, scale, whatever you want, up to minimum standards. It wouldn’t meet our minimum standards that we wanna house animals there. We did use it for like kind of off exhibit. We did use it, but nothing for public display.

As a general curator and an interim director, were you still able to make rounds, which were important?

I wanna say I didn’t do it as regularly. I really don’t remember doing it as regular ’cause I did start doing it.

Then again, after Dion was hired and things went back to relative normal and that was then a different kind of round because then I would be making a round and then talking to the curator or curators saying, hey, what’s happened with this?

What’s happened with that.

Is this good, is this bad, do you need help?

I mean, I don’t know how often I said that. I should have said that more often. Certainly, you become wise in your years, I like to do a lot of things over again that I did previously in my former life.

As interim director, were you purchasing animals at the time or you that everything stopped?

Yeah, that really stopped because A, money was tough. Money was an issue. It was keep the place, open that up every day and close it every day and have everybody safe. We weren’t making plans for expansion during that time. I mean, you wouldn’t wanna bring a new director in and all of a sudden have him, I wouldn’t wanna bring in a new director in all of a sudden saying, not that it’s been that long of time. It’s been a short time, oh, we wanna do this, do this. You have to do that, so no, nothing. It wasn’t a large planning phase.

You mentioned that you were talking with people downtown now as an administration, making contacts and so forth.

Did any of these people who were obviously maybe higher position than you say to you Mike, we’d like you to be a guy?

I don’t remember saying that, but I know some sort of conversation had certainly came up because I did make it clear. No, I don’t remember the details of the conversation, that I said, I’m not interested. I’m not interested in a position. I just wanna wait, take care of things until you hire a director.

So when that was mentioned, I’m not sure if it was me coming forth, Mike, are you interested in position?

No, I don’t remember that. How long were you. Six months. I’m sorry, about six months. And they had, I mean, during that time, the city had brought in a couple people for interviews and I would be showing them around to the zoo, I was the zoo contact.

Was your input for a new director solicited by the people from the city?

No, not that I remember.

And when the new director came in, did you know him previously or he was new to you?

I knew of him, I knew the name. I had never met him, once again, it was so early in my career and going to conferences where you meet people. When he was the new director, and they used to have five, I think it was five regional conferences back in those days, he was in the east and he would probably have gone to the Eastern conference and then nationals, and I wasn’t doing nationals at that time. So make a long story short. I knew him because of his Lincoln Park experience.

He knew of you?

I guess when he applied for the zoo, I mean, I started checking on me. I wasn’t the name in the business at that point in time. Not that I’m a name this at this point in time, but it was certainly so early in my career. I mean, whether he wound up contacting anyone at Lincoln park because he would’ve known, I came from there. He may have done that, I don’t remember that.

You mentioned that you talked to one of the former directors, Frank Thompson, when you were heading the zoo, were there other people you reached out to, or were there people that reached out to you in a mentorship kind of role?

I talked to people at Lincoln Park on various occasions, sometimes just to, I don’t remember specific conversations in terms of, hey, I have this problem.

What would you do, what would you recommend?

But I certainly would call these people These are some of the few people that I feel I knew more than just colleagues, that I could sound off, blow off some hot air, just relieve myself. ‘Cause I didn’t have that. In Evansville, I didn’t even have, I mean, I was young. I didn’t have family there. I couldn’t go home. I guess I yelled at my sheep dog and told Chauncey what I thought of the day. But you know, there was no one really there for me to talk to. He was so early in the career.

The new director comes into the zoo.

Did he immediately start to make changes or discuss changes with you zoo change direction?

What were they focusing on all of a sudden?

Initially when Dion came in, he had his learning curve too. See what the facility was, see how the city was to work with. There was always a zoological society there that at that time, about the only thing they wound up doing is producing a newsletter quarterly for their membership, probably, and it couldn’t be held. It was in the hundreds, it wasn’t in the thousands of members, and they ran a little gift shop in the clay building that was opened sporadically, not on a regular basis. And that was only on weekends. So didn’t have a society really to work with and all during my time at the zoo, the society never really longed for a larger role in the zoo. I believe that’s changed now, but they knew where their place was or what their place was. And also was aware of the city.

I mean this, once again, seventies, Though Evansville changed. It had been a long time democratic city. And then in the seventies, there was a Republican, there was a change, Republicans came in and hadn’t been there in office for, I don’t know, 60 years, 70 years, some very long period of time. So there was lots of changes with the city government and how it’s working. So once again, with them, he had to have his learning curve. That being said, I never remember having anything of a master plan at Evansville to the day I left. I mean, I don’t even know if the word had entered my mind, my lexicon yet the zoo hadn’t changed for years until the mid seventies, when we got the SEEDA money and were able to start some changes, I mean, after that, there were some changes with the zoo, but it was almost like, it was very haphazard. What we did or didn’t do.

As we progressed, the old building that we had the chimps in and the other primates that we had at the zoo and the other cats, other than the lions, we eventually closed that building to the public, the exhibitry was horrible. It wound up, we changed it into a hospital, so to speak where we could hold and treat, had some facilities to deal with some animals larger than a darker cat dog or cat. So that was done. I mean that eventually, the building was in such disappear. I know it has totally been taken down, I don’t know, inconsequential to my relationship at Chicago.

When Dion came in, did he lean on you to ask you your advice ’cause you obviously had been at the zoo and what you thought might be changed?

As I remember it, yes. I mean Dion was very low key. I don’t remember him really getting emphatic or yelling or, need this done tomorrow type thing. He was very easy to work with and accepted my input. And he also gave me more freedom with some of the collection, you know, changes of the collections, collection management. I won’t say it’s more, but it was certainly much more than John had in terms that I had. I need a break. You mentioned that the new director gave you more latitude.

With that latitude, what did you start to try and implement at the zoo?

It’s difficult for me to remember a lot of specifics so many years ago, I mean, literally, it was over 35 years ago, probably closer to 40 at, yeah, probably about 35 years ago. In any event I got, I mean, one of the things that I enjoyed doing that once again, no one else would do. It was the records and ISIS started becoming, it was being implemented. I mean, at that time, everything, there was no computer. We had no computer at the zoo and we were inputting information. I mean, we had this card stock that had a carbon copy and we’d be filling out all these numbers for these animals. And I guess I was fascinated about, I was totally fascinated about computer inventory. I remember the Topeka zoo, Paul Linger was the assistant director there.

And I think, to me, he was the first person zoo person ever had a computer to use and was using it for different reasons. Anyway, I’m drifting. I was very interested in the inventory and basically the history of the zoo, of the animal collection. Something that I felt at Evansville was lacking and it was probably, lacking no more than other facilities at the time where they keep records of animals, you’d see card stock that said acquired antelope, and you go, antelope, eh, I wonder what it was, it could have been anything, it was the records, no one or many or most, I’m not sure what the word is. People didn’t care about the history of the animal, it was just here and now, we have the animal now and where it came from. We may not know or where it went, once we get rid of it, it’s no longer, in our purview, our record, opposed to some institutions. Now it’s created the grave responsibility for animals, but I was fascinated and I really enjoyed doing that part of the job. I didn’t have a daily routine, for every hour I had, as any zoo manager does, they have freedom to do stuff, whatever that stuff is, to a degree they could do it every day for as long or short as they want, as long as they have to meet the criteria that’s given to them from the manager.

So you’re saying what did Dion give me, whether he had confidence me, whether they had respect in me, he left me to my own devices, I guess. I mean, there wasn’t a day that he had a small off, everybody. I had a bigger than him actually, but also my own office was at the library and store room and everything, you know, there wasn’t a day that I wouldn’t be going into his office with a cup of coffee, and we’d sit and talk about the zoo or zoo stuff, or reliving stuff. I mean, which was learning to me every day it happened. I mean maybe twice a day had many days to just come in. We just did this, that happened. He was so much easier for me to communicate with than John was. And Mesker Park wasn’t a scientific institution.

Mesker Park was a zoo. And the purpose of the zoo, at that point in time was for us to maintain a collection of animals for the people, the metropolitan people of the tri-state area to come and see and enjoy.

With your newfound freedom so to speak, were you able to go to national conferences?