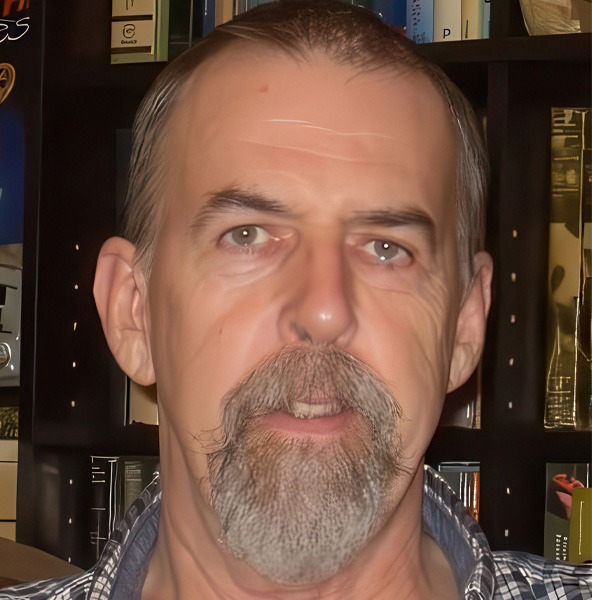

I’m Douglas Richardson. I was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on the 20th of May, 1957.

What was your childhood like?

Initially, very stable and then my family decided that the grass was greener and we did the worst researched immigration to North America.

Since the pilgrims, What did your parents do?

My mother was, she did a bit of office work. My dad was, and Scotland was a proof reader for various newspapers. When we eventually ended up in America and getting a job in the papers, it was a union closed shop and my dad ended up being the assistant gardener on the estate of the granddaughter of JP Morgan.

What are some of your loose memories of zoos Going to Edinburgh Zoo on Easter Sunday?

Most years before we immigrated to North America, some, I mean, I can remember very vividly my first trip to London Zoo was in the summer of 1966. We were down on a family holiday, beautiful hot day, which most Scottish people are not acclimated for. And my parents being exhausted and allowing a a 9-year-old child just to wander off around the zoo on his own, which I was, I was having no argument with that. And there was a couple of zoo programs on, on British television, on the segment of British TV that was aimed at children. So this kind of four o’clock to five o’clock window and one was called Zoo Time and it was hosted by Desmond Morris, who was used to be the curator of mammals here. And, and so when I visited the, what is now called the Cassen House, which was originally the Elephant Rhino Pavilion and the Snowed Avery, a large walkthrough, Avery had just been opened. So, and I’d seen them on tv. And so seeing one, seeing London Zoo in the flesh, the one thing that was disappointing is chichi, the giant panda was on breeding loan to Moscow that summer.

So I didn’t actually get to see a giant panda till till much, much later. So yeah, my first zoo was Edinburgh Zoo. My second zoo I visited was painting zoo again on a family holiday. And my third zoo was London Fourth Zoo, probably Riverdale Zoo in the old Toronto Zoo, which was really disconcerting because in Britain we don’t have free zoos. And I remember my dad we’re walking through and we realized we were actually already in the zoo and he actually had his wallet out looking for somewhere to pay. And the idea, we thought we’d snuck in ’cause the idea of of a free entry zoo didn’t exist. So that was, that was peculiar.

When you were young, did you have the idea of working in a zoo?

Absolutely no question. That the it, I just wanted to know every aspect of them, what went on behind the scenes. I mean, as I, I think I, I mentioned earlier or about Joe Davis at the Bronx taking me on a behind the scenes tour after my, my chat with him and, and then going, you know, down into the Old Lion House basement and all the mouse deer and rabbit hutches and, you know, all these animals off exhibit and how this worked. And, you know, meeting, he actually just came in to ask for some leave. Mickey Quinn, the the keeper that used to look after Oka the gorilla at the Bronx Zoo. And then Joe telling me a story about Mickey Quinn, who was apparently a big circus fan. And he all, when Ringling Brothers came to Madison Square Garden for two weeks, he had one week’s leave and then one week sick. And he was at the circus every day.

’cause he knew all the guys in the circus. So it was, it was that, it was that first look behind the curtain as to how worked, and I mean all that did was, you know, it just made me even more wildly interested to find out more to be, to be part of that community. So now your career, 1975 to 1980, you were a keeper at the Edinburgh, the Bronx and Loman Wildlife.

First of all, how did you get your first J Zoo job at Edinburgh Zoo?

I’d started out as most people do, by writing letter after letter and getting no result at all. And I’d actually been living in London. I’d come back from America to, I’d been half promised a job at London Zoo that never materialized. And so after doing a bit of pub work and a bit of work in parks, I was sharing a flat with my uncle and aunt and we ended up, my uncle’s job ended up moving back up to Edinburgh. He was in research.

And so we all moved back up there and I went into the zoo for a visit and I was chatting to one of the keepers and it was, I said, do you know, is there any vacancies?

He said, yeah, actually there is. And so I managed to get an interview off the cuff that day and called up a week later and I was like, I’ve not heard anything yet. He said, alright, right, yeah, you’ve got the job. And that’s how I landed my first zoo job. Plus thinking that they’re gonna have me looking after at the Children’s Zoo or working with Budgies or something. And I was, you know, put in the wine house on day one, you know, couldn’t get any cooler than that, you know, But you leave Edinburgh and you go to the Bronx suit.

Yeah. Why?

I went back to, my parents still lived on Long Island and I went back for a visit and, and of course I visited the Bronx Zoo. And again, you know, I was curious that, you know, any vacancies, I got an interview with the head of, I suppose what we passed for HR and said, right, you know, you show up in a couple months, you know, give you a job. And so went back to Scotland and went through, I had to go through the immigration process again, which in those days, getting a green card was not particularly difficult, particularly when your parents or lived in the States and, and got a job at the Bronx Zoo. ’cause it was, you know, it was the Bronx Zoo, you know, this was a serious Sue Edinburgh. I was still an important collection, but a fairly parochial one at that time. So getting offered a job at the Bronx Zoo and then sort of rocking up and it turned out it was me and one other guy that were the only recent, well actually we were the only keepers that had previous zoo experience. Everybody else had been Bronx Zoo man and boy. And who was the director at the Bronx Zoo when you were there, Bill Conway.

Did you ever, ever have an opportunity to interact with the director?

My first interaction with, with Bill Conway was amusing and unfortunate. They had not finished, opened Wild Asia and they had it a weird system, Astor, who had basically bankrolled the, the Wild Asia project. She’d given some money for a party, but they couldn’t have everybody there. So if you’d worked at, at in Wild Asia, 11 times or more, you got invite to the party. And as luck would have it, because the way the keeper system worked there on the mammals, you would get dodged about from section to section. And so I’d done 11 times at Wild Asia.

And so I got, and I was only there, I’d only been there a couple of months at the time and I’m in Wild Asia and, you know, being the, the zoo freak that I am, and you know, I’m looking at all things like, well, you know, why have they do, why have they done that way?

Why have they done it this way? Anyway, I’m stand, I’d had way too much beer and I’m standing on the loading dock and this guy in a suit comes up and he goes, well, so what do you think of Wild Asia?

And I was like, well, I’ll tell you.

And why have you got heated areas for the ammo tigers?

And you realize that the roofs in the Indian rhino stalls are too low, so you can’t put rhinos together. Otherwise, the male, when he mounts the female is gonna go through the ceiling and apparently you’ve only got two and a half tons pressure on the hydraulic doors on the elephant. So when a five ton bull steps in the way, you know, it’s basically gonna force the door open. And I looked over his shoulder and there was keepers behind him going, no, that’s Bill Conway like that. And I’m going, yeah, okay. And another thing. And then I stepped backwards and fell straight off the loading dock onto my back. Bill Conway did not ask how I was doing. He just turned and walked away.

So that was my first interaction with, with Dr. Conway. But you leave the Bronx Zoo and you go to La Loman Wildlife.

Why did you leave the Bronx? And where is La Loman Wildlife?

La Loman Wildlife Park no longer exists. It was originally called Cameron Bear Park. It was the Chipperfield organization who started all the safari parks. They looked at a different model. So instead of Africa, they’d do a bear park. They actually had a drive through polar bear enclosure, which didn’t last very long at all. I’d been promised to a job running the primate section at Glasgow Zoo, which also now no longer exists. And because I was being career minded, you know, I was looking for that promotion and I came over and again, it was like, when I came to London originally, the job wasn’t there when I arrived.

The director had made promises that he couldn’t keep. And so I was like, I was at a loose end that they were looking for a, a manager for the non drive-through area at the Bear Park or Cameron Wildlife Park. And, and so I opted for that for a few months. And so that was based, so I ended up as, as with many of the places I worked, it wasn’t necessarily the initial plan. But you’ve worked at three Zoos now. Did you start the form a philosophy regarding zoo management at that time or no, I suppose an, an embryonic approach looking to make it as professional as possible. This, I, you know, I was still, it was still an era when, you know, zookeepers were looked down upon where zoos as an institution were not held in particularly high regard unless you were a London Zoo, for example. So I suppose it was like, okay, right.

How, how, how do we raise the game, I think was what I was, was my philosophy.

How, how do we make it better?

How do we, how do we educate keepers?

How should we be keeping our animals?

So I suppose a lot of the things that the zookeepers of today would rather take for granted didn’t exist or, or were, were in a, they existed, but maybe in isolation. London Zoo had a keeper training course, but it was only for London and Waid staff. And it actually, it, it acted in part as a basis for the National Keeper’s course.

But yeah, it was how, it was a philosophy of, okay, right, how can, how can we improve this?

How can we turn this into a profession, which it wasn’t From 19 80, 19 84, you’re the head charter war keeper, how Howlet Zoo Park, how do you get to Howlet Zoo Park?

A guy I used to work with at the Bronx, Jim Cronin, he was working at Howlet managing the small primate section as a, and the, there was a vacancy for the head of the carnivore section ’cause the head keeper had been killed by Tiger. And so Jim had sung my praises to John Aspen, all the owner. And I came down for an interview, which we did on the hoof as we’re walking around the zoo, got the job back up to Glasgow, packed up all my stuff and, and came down to hers. Was there pressure, because John Aspenal was kind of bigger than life. Was there pressure on you to go in with the animals Every single Sunday when he did playtime with the tigers or some of the tigers Dougie coming in today. And it was, my answer was always, no, not least because 11 days into the job, the former head keeper’s second in charge, who was serving his notice got killed by the same tiger in front of me. And there was no way, you know, I was playing those games. That said, there was about three or four times where it all went wrong when Aspenal was in the tiger enclosure.

And basically I went in to chase the cat off to get him out. So there were a handful of occasions where I did go in with the tigers, but it was always to basically save his life. In 1984 and 1986, you’re now overseer of carnivores at Dudley Zoo. You leave Howlet because, and you go to Dudley. How come A very good friend, mark Akin, who cut his teeth as a keeper at Howlet, partially on the cats, but primarily on the elephants. And then he went down to work the elephants at Portland and he got killed by one of the bulls.

And for me that was, it was okay, right?

I’ve, I’ve, I’ve seen enough friends getting killed or, you know, been in the proximity when they have been. It was like, okay, right, I need to find another job. And that was the first sort of head of carnivores position, if you like, that had come up. And so I, you know, applied for the job and got it at Dudley. Now in 1986 to 91, you become head keeper of carnivores at the London Zoo.

What kind of zoo did you find and how do you get this job?

My opinion of London Zoo had changed. We’d always kind of, in the Scottish contingent, we’d always seen it. No, we had good friends down here. We’d always seen it as a wee bit too regimented. But Dudley Zoo was not, was, was not well funded. The senior management team, the, the chief executive in particular was a very un unpleasant individual. And so I knew that Ernie Swain, who was the head keeper of, of carnivores, the Winehouse here at London, I knew he was retiring and I applied for the job even though they’d never advertised it. And London had never advertised a head keeper position ever.

And anyway, couple weeks I’d gone on holiday, I’d come back and the chap who’s just recently retired as director, him and I were sharing a flat and Dudley and, and Derek said, oh, Brian Bertram, who was curator of mammals at London at the time, said, he’s Doug, Brian Bertrams coming up to the zoo tomorrow to have a chat with you about the head keeper job. And I was like, yeah, right. Pull the other one. And he’s going, no, really. And it wasn’t until I got into work the next day and the curator came up to me, said, Brian Bertrams coming to see you today, so you’ll be here about two. And I was like, oh, right, this is real. So we had a chat and it was, I was told, this is, you know, this is off the record, you know, you’re not allowed to tell anybody. ’cause London had never done this before. They then advertised the job and they asked me to apply formally and then went through the interview process and I, about three interviews for the position, it was hugely controversial.

London was Unionized Zoo. And you know, here’s me taking one of the few options for promotion and some outsider, some young outsider, I mean, I was 29 at the time, and most head keepers when they finally, you know, walked into the dead men’s shoes, that was their, their predecessor. They were usually in their, their forties, late forties by that stage. So it was unprecedented in a range of different ways. I remember my first day, I don’t think I’d received that much uniform from a zoo that I worked at.

And for, if we added all the uniform I’d ever received from every zoo I’d ever worked at, it wouldn’t have amounted to the double arm full of stuff that I was barely able to see over the top of being Charlie Kitchen side, a former o overseer taking me up to the stores, right?

You need two pairs of them and three pairs of those. And tr I even got socks.

I said, I said, where’s the underwear?

He said, that might come next year. So it was, it was a, I thought at that point that’s in my zoo career. I thought that I’d, I made it, this, this was, you know, no one had done this before and, and you’re at London’s, the Zoological Society of London with all the history behind it, you’re now a head keeper there. But in 1991 you become the collection manager at the London Zoo. There was a, this was the start of the financial, real financial troubles at the zoo. And so there was a huge, there was a major redundancy program of animals and people, about a third of the staff lost their jobs, including some of the curators. They created new positions that we all had to apply for. So I applied for one of the animal collection manager.

So I actually applied for the assistant curator, ’cause I thought that sounded better, but they wanted me for a collection manager position. So that was, I suppose the, my first foray into a curatorial position. But though I got promotion, a lot of my colleagues lost their job. So it was, one couldn’t, there was little cause for celebration at the time, if you know what I mean. But in 1995, you’re now curator of mammals at the London Zoo.

Yeah. How did that come about?

Basically a little bit of making an argument for it. The, one of the other collection managers wanting to step away from that side of things with the, with exotic animal sections. And it, it was my aspiration curator of mammals at London Zoo. Certainly in the UK scenario, and maybe to an extent internationally, certainly within the uk it held as much kudos as most other director positions. So it was one of the golden jobs. And so after watching Zoo Time as a kid with Desmond Morris, I now have his job. But yet in 1999, you leave London Zoo to become the director of the Rome Zoo.

And, but for a short period of time, how did that come about and why did you leave The where did I leave London or why did I leave Rome?

Why did you leave London to go to Rome, but such a short time and then leave Rome?

They, an ex-girlfriend was involved with, she was managing the Genoa Aquarium, which was, it was the same organization that had now had the contract to manage Rome Zoo. And they were basically looking to, they, nothing new had been built since the 1950s. And so basically they were looking for someone to basically rebuild the entire zoo. And so I, I’d been to Rome coincidentally the previous year on holiday and seeing the zoo and in all its flaws and, but you know, obviously, you know, Rome was one, it was at one time one of the great zoos of the world and, but had definitely fallen by the wayside. And so the opportunity to rebuild it was quite attractive. But, you know, not long bought a house in London, cur of mammals at London Zoo, had no particular desire to move. And they kept calling.

And I eventually when asked, okay, what will it take?

And I, I gave the, okay, I, I gave what I thought was a ridiculously large amount of money that they would have to pay me. And then they called me the next day and said, right, we’ll pay you that. And it was like, oh, Douglas, you pr So basically I’d, I’d argued myself into taking the job, but I jumped into it. It was interesting. I discovered that I had no particular foreign language skills after going to Italian lessons twice a week I can hold a conversation with a mentally defective three-year-old child, order a beer. That’s about the extent of it. I had a real problem with the lack of a Celtic work ethic in a Mediterranean culture. They’d also, when the, this private company had taken over a, a, the vast majority of the, the keepers who were or municipal employees left to take out, they were offered other jobs within the city.

So there was only a handful of experienced keepers. Then they hired all these university graduates who didn’t know the first thing about working in zoos, but all had very firm opinions of how it should be done. And it was, it was an incredibly frustrating experience. But, well, I got a few things done, got a few big projects, finished master plan for the zoo, hired my successor, and I was headhunted for a place in Canada. And you go to become the Chief Operations Officer, general Cur Mountain View Conservation Center, and you are there for a short period of time, but then you go to the Singapore Zoo. How did the Singapore Zoo come about In 2005, I had a parting of the ways with the owner of Mountain View who’d gone through quite a number of staff before me. Not a pleasant person, not a pleasant experience, and then just trying to get a zoo job. But try, obviously when you’re up to a certain level, it becomes less of a target rich environment.

And then I’d, I’d applied for various positions in the states without success, not even getting interviews, which I thought was strange.

I was curator of mammals at London Zoo. What do you mean?

I don’t have an interview and a curator position at Singapore came up. I applied, they got straight back in touch with me, flew myself, my wife out to have a lookie and an interview, obviously very interesting place, fantastic zoo, amazing animal collection. And so it was like, okay, right. There was nothing else on, on the card. So took the job there and had a, a three year contract and it was really useful to have had three years experience in a tropical zoo with all the unique problems that you have in the tropics in a zoo that you don’t have in a temperate zone zoo. So our idea of vermin wasn’t so much mice and rats and cockroaches, but spitting cobras, black scorpions, and very large reticulated pythons that were trying to kill your monkey collection. And, and then in 2008 you leave Singapore and you become head of Living collections at the Highland Wildlife Park and you win the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquarium First Trailblazer Award for a revolutionary polar bear exhibit.

What was the revolutionary?

Most old polar bear enclosures had basically been lots of concrete, lots of steel. I think the a ZA recommendations for polar bears is still a 16 foot high fence. And I went, I was asked to rehouse the single, so the, the last zoo polar bear in the uk it was an old female at Edinburgh Zoo or, or Sister Zoo. And, and they wanted to do something very different, large area, but there wasn’t much money available.

So I had to come, okay, right, how can, how can we do this cheaply?

And so it was devising a barrier technique that was inexpensive, which also enabled you to fence in a very large area. And that was, that was kind of the turning point in the change in how polar bears are kept, certainly in the uk.

What do you think made you a, a good manager?

A good zoological manager?

I think probably the most important aspect is having started from the shop floor as a baby zookeeper and working my way up. So I had a good understanding of, of what to expect from people, what they should expect from me. So having worked for a, a wide range of good, bad and indifferent bosses, then I, I, I would like to think I had a, a good idea on how to approach dealing with people and be a, a good manager from the animal side of things. Having worked with a wide range of species, primarily mammalian, I was able to get a very broad and deep understanding of how to manage primates or carnivores or elephants or ungulates and relate that to, to how I dealt with the staff and manage the animal collection. I mean, I remember being told one story, it was a curator who had never worked in the zoo before and immediately came in as a, a curator of mammals and asking the keepers and the story just went around the zoo and it was from some years back, so how many oranges do you feed the sea lions, you know, and it was that, and so what the keepers also knew about me was they couldn’t pull a snow job on me either because I’d done their job, I’d worked with their animals or at least, you know, similar species. So I suppose having, being able to generate that level of respect as well as respecting them for what they had to do, I think that’s what I, I would think, I think that’s what made me a good zoo manager, zoological manager. Now you’ve done many jobs in, in the zoo profession.

What skillset do you think a zoo director needs today as compared to when you started?

I mean, zoos have become much more complex organisms, and I mean, particularly when one is looking at it from a, not so much a UK perspective, but say a North American or a continental European perspective where your zoo is funded by local government, one doesn’t necessarily, you certainly didn’t used to have to have any kind of financial chops. Nowadays that’s very different. The the whole social media marketing, you know, in being in the public eye is a lot more intense than it ever was when I started in, in, in the zoo game. So the skills that are needed are varied. My concern would be that in many cases, the, the key understanding of having a zoo background of having, you know, worked on the animal side, the, to use a mark marketing parlance, the, the core product of the, of the industry that we’re in, many CEOs don’t have that. And so they sometimes, the only people they can understand are those in marketing, are those in finance, because that’s the language that they have learned to speak. They don’t speak zookeeper, they don’t speak zoo curator. So when, in this day and age, when there is a, a zoo director that ha has come from a zoo background, but has also developed all the other skills that require, they’re, they’re an individual that warrants a, a level of respect that I may not feel comfortable in giving to one who doesn’t come, who’s just come into the, the zoo community from the outside.

But at a very senior level. I’ve seen a couple of good ones. I’ve seen a lot of bad ones. There are many zoos. They’re small, medium.

What do you think a small or a medium size municipal zoo could do today to be involved in wildlife conservation, either on a national level or possibly internationally?

There? I mean this is a, this is a, a subject that comes up quite often and, you know, for, for smaller zoos being okay, how, you know, there’s no way I can be a zoological society of London or, you know, WCS or San Diego. They just don’t have the capacity staff, financial, whatever it might be to do that. But there’s a, there’s a tiny little zoo in the southwest of England called Sheldon. And I mean, it, it literally is a couple of acres, maybe five maximum. They punch way above their weight and they take on, and it’s not just local projects, it’s international projects.

And so, you know, being involved with you, something like, you know, pangolin conservation in Vietnam is okay, right?

You know, you need the commitment, you need to be able to raise the money to attend meetings or make a contribution to a center in Vietnam or wherever it might be. And being able to, and everybody’s gonna have access to, there’s gonna be local people with money that might be able to contribute towards something like that. I think the, the, the limitation is only down to the imagination of the individual. You don’t have to be a Bronx to make that, you know, you’re not funding an entire national park. You’re doing whatever you can do. And certainly in the UK there is a, there’s a lot more emphasis on looking at native species than say was the case when I came into the business where, excuse me, where paying attention to local species conservation was not on anybody’s agenda. And that was very much certainly in a, a UK zoo scenario is very much on, on people’s agenda. So there’s a good chance that just small zoo, right, you know, maybe you can’t make a contribution to tiger or rhino conservation, but you can probably do something for red squirrels or reintroducing pine martins or the in, you know, the numerous number of invertebrate species that are in that are critically endangered and in some cases extinct in the wild.

Everyone can afford to have say a commitment towards an invertebrate no matter what size your zoo.

Well you talked about finances and, and considering financial resources available to the small or the medium sized zoos, what do you think should be the focus of those kinds of collections?

Should it be regional endangered species, more typical collection of the endangered or non endangered species?

What kind of collection should those small and medium zoos try and achieve In this day and age with the state of the planet?

I don’t think any collection, no matter how big, medium or small it may be, I don’t think they really can afford not to have a collection whose major emphasis is on highly threatened species. Be they as part of insurance populations, be it as part breeding for reintroduction or basically as say in the case with tigers in this day and age, we’re not really looking at reintroduction at the moment. They are there as flagship animals for their, for their wild counterparts.

They, I mean, do we need another meercat exhibit?

Do we need another African plains exhibit with common African stock on it?

I don’t think we do. So the emphasis I think has to be on threatened species and you can still have a representative collection, but everything will have a, a conservation emphasis.

Can you talk a little, can you talk about animal welfare groups in Europe and their relationship with zoos?

Can you give us your thoughts on that?

I mean, if you’re, if you’re talking about groups that are and are in particular anti zoo, would that be correct?

Correct. Okay. Dealing with them is, for me is almost as much fun as having sex. Many years ago when I was working at London, there was a very important or very high profile anti zoo group who were launching a video and there was clips of London Zoo on there and we managed to get a look at it and they were having a press conference and I managed to convince my then director to finally let me off the lead. And I had to take someone from the press office with me. You know, there had to be a grownup in the room to make sure I didn’t do anything silly. And they presented the video and it came to the sort of question and answer period. And there was lots of press there. And to their credit, and the individuals who were high profile in this group knew me and I put my hand up and to their credit, they called on me.

They could have ignored me. They didn’t. And so I stood up and I immediately said, right, I’m Douglas Richardson, I’m curator of mammals at London Zoo and all the cameras just immediately sit drowned. And, and I just caught them off guard. And I said, look, there was, there’s, you know, there’s, there was images in your video that any good zoo person would be happy to stand shoulder to shoulder with you and, and agree that, you know, someone should be, should lose their job or be prosecuted over because of what, what you showed on the video. And you could see them going, that’s not what we expected. And then it was, but you, you had images there. You didn’t name any of the zoos, but there was a, there was a black manga bee monkey from, it was obviously an Antwerp zoo and it’s pacing up and down.

I said, did you bother to ask what was the history of that animal?

And, you know, ’cause there was lots of, of Belgians that lived in what was then Zaire. And under the new regime they came back, they came back with pets. And when the manga be trashed, the living room, they ended up at the zoo.

Did you find out if that was one of those animals?

And I used about three examples like this. And you know, I said basically, you know, don’t paint us all with the same brush.

Anyway, the BBC producer that was there came up to me, said, would you be interested in doing a debate with them live on BBC?

And it was like, oh yeah. And we did a very long, it was, I think it was a good two or three hours debate on Radio four, major UK radio State National Radio station. And I’m proud to say that I think that won the argument. But what was interesting was the zoo community, particularly in the UK when organizations like the Zoo Czech or which became the Born Free Foundation, when they came up, the, the policy of the, the British and Irish Zoo Association was ignore them, they’ll go away. And that never happened. And all they got was more column inches in the Sunday papers and whatnot. And, and what I’d been pushing for was a much more aggressive, let’s take these guys on, you know, when they, when they raise their head above the parapet to give them a proverbial slap and to take them on publicly. And so when my director was, at the time when he let me off the lead and I was able to do this, London Zoo was the main target.

You know, the, the, the National Zoo. The most important collection, most high profile collection in the uk. We were the big target. ’cause if we could, they could take us down. Everybody else was easy. But during that period, every time they raised their head above the parapet, I was there to give it a slap and then they stopped. So having this, and I’ve, I’ve spoken with a number of zoos about this one, I did some work for most recently who have serious problems with a, a local anti zoo group. And it was like, you have to take these people on.

I said, and you’ve got knowledgeable people. You have, you, you, you do the interviews, you do the debates, you use examples you make, you’re not just arguing with them. You’re informing everybody on the outside who only sees their argument, only hears their argument because you’re not saying anything. So I’ve always opted for a more, shall we say, aggressive stance. But it in a lot of ways it, it’s a protective stance. I’m proud of what I do. I have no problems with the word zoo or anything like that, which I know a lot of people in the, in the community know, oh, well, you know, it’s not zookeepers anymore, it’s animal caretakers. There’s a, there’s been a whole almost a, a, a hazard to say a woke approach to the terminology we use.

But then I’ve seen a lot of places where they’ve changed their names. They’ve gone from, we’re, we’re no longer a zoo, we’re a wildlife center. And then all of a sudden their visitor numbers go down because the public don’t know what they are anymore. And then they go back to calling themselves a zoo. And it’s like, oh yeah, that’s, yeah, I remember that’s what you are. We should be proud of what we are, where we’ve come from and where we’re going. And the place that we have within the international conservation community because the Good Zoo community is now one of the most important forces for good when it comes to conservation. Sorry, that was a very long answer.

Great zoo must compete with other cultural institutions.

What do you think there is their strong point and how do they sell it?

You go to, I mean, there seems to be a lot of zoos these days that have lost faith in their, in the, in what they do. And so they now have to have animatronic dinosaurs and Lego sculptures and various other non-animal aspects to their operation be that, as, you know, temporary exhibitions or in some cases permanent ones. And some places do them better than others. The last institution that, where I was running the animal department, the Highland Wildlife Park in Scotland, everything we did was animal focused. It was almost like an old school approach. The species selection was all cold weather adapted stuff. But I made sure that we had animals, that we had breeding recommendations for that, you know, we, we had lots of baby animals on the ground. We made sure that I used to do a, a column for a local newspaper and, and that was once a month.

We made sure we had a, a fluffy news story every month and a serious news story every month. And this was during the worst financial recession since the Great Depression. So basically from 2008 when I started and when I left, we had more than doubled the attendance level during that harsh period. But it was, it was an old school approach. Zoos are, the focus is animals. And, and yes, we had a lot of baby animals, but it was all always for good reasons and, you know, but it was the, we had that level of publicity. We ended up getting a huge local support. And because in the central Highlands of Scotland, it’s a huge tourist area.

We got to the point when people are staying at small hotels, right?

We have a spare day, what do you reckon we do?

Oh, you should go to the Highland Wildlife Park. It’s brilliant. You know, they’ve got tigers and polar bears and, you know, and huge enclosures. It looks fantastic. And so we were able to completely change the, the, the significance of the collection, both in the eyes of the, the local population and the, and the eyes of the general public and in the eyes of the, the professional community in the, within the zoo community. We, we raised our profile considerably, but it was all animal oriented. And I think that’s what a lot of zoos, they miss that one though. They think they have to do something else, and I don’t think they do.

Now you’ve been in this position many times, what would you include in a training program for curators?

I did a, I was asked to do a talk at, it was actually a keeper’s sort of three day workshop called Keeper Fest at a place called Jimmy’s Farm in Wildlife Park down in, in the south of England.

And they asked me, I said, look, can you do a talk about what it takes to be a, a good curator?

And it was like, okay, right, okay, this is, this is right up my street. And so I basically, I came up with a list of, I think it was 16 key points. What it starts with is you have to have been a zookeeper. You, you, you ha you know, you know, whether it’s, that’s the level you came in at or whether say in the German system where you might be a trainee curator, but you’re working on the animal sections as well. So you get that, that firsthand experience. There were things like, you know, I’ve, I’ve worked with people where we’re doing a new project. Here’s the, here’s the new exhibit that we’re building, here’s the plans. And they look at a plan and they, they don’t know how to read.

So they can’t make intelligent contribution to it. I mean, I did a job in Rome and we had a, a a, a zoo architect firm doing the new bear enclosure. And, and I wasn’t happy with, the exhibit was great, but the holding area was, I didn’t think it was particularly safe and it was clumsy.

And so, you know, I said, look, you know, can I need to change a few things?

And it turns out, because of planning permission, we had to stay within the footprint. And so over a lunchtime, I changed the interior design.

And the architect was like, how did you do that?

I said, well, I’ve, I’ve always been interested in zoo architecture, but I taught myself how to read a plan, how to alter it, how to use tracing paper to basically come up with something new, another be kind to the maintenance department. That’s absolutely crucial. When you want a nest box made for something, you, you, you want them on side. You know, you want them to be interested. You, you want them to know that you respect their skills, which rolls into never be too proud to learn from anyone. When I was working in Singapore, we had to catch up all of the false gals. I was having the area modified, so we had a better chance of breeding them. But we had to, you know, we were creating barriers.

We had to catch up and move them. And I’d never caught a big crocodile before. And so the, there was a number of keepers at Singapore that had a lot of crocodile experience. And I said, right, okay, today I’m working for you. You have to tell me what to do. ’cause I’ve never done this before. You’ve done it. I’ve not, and because of the Asian mentality, giving the boss instructions is a really hard thing. And there was a couple of times where the guys were like, no.

I said, come on. You know, I said, tell me what to do. And anyway, they, they taught me how to catch crocodiles. There was one guy who was getting a bit cocky by the end of the day and giving me lots of instructions of, okay, right, you’re pushing it now. But it was never be too proud to learn from anybody at whatever level. You know, they, the, everybody has a contribution to make. Having people, being able to give your staff the, the, the permission, the power to be able to contribute to a discussion, to come up with a new idea. You know, I would do the designs for new exhibits and Right, I’m leaving, here’s my drawings. I’ll leave it on the mushroom table. Right.

It’s time to you guys. So have a look at it, you know, have I, you know, have I missed something?

Is there something else that you’d want there?

I did a job recently for Dundee. They wanted a new gibbon enclosure.

And I said, right, what have you got?

And the keepers had done some drawings and I made sure that everything they wanted was incorporated in the plans I gave them. And it turns out everybody was really happy with it. ’cause I, I took what they had and made it easier because I’d been a zookeeper. I know what it’s like to have to go through doors that are half my height and catch your back on it as you’re going out or coming in. I’ve never understood why a lot of designers and architects thought that keepers were tiny people. So it’s, I think having a consideration for others, a trust in others, and are an in depth knowledge of the job, of what it entails and the animals that you’re responsible for. And never fake it. If you don’t know, say you don’t know.

What changes have you seen during your years in, in the zoo field regarding visitor attitudes?

Huh. I mean, certainly when I was first brought to zoos as a child visitor, which for me was the, the highlight of my year, certainly the uk the, the zoo visiting season opens on the Easter weekend. And so going to Edinburgh Zoo where I was as a young child was, for me that was like the best thing ever. And obviously in that, in the, those early, very early sixties, feeding animals and whatnot was very much accepted. It was part and parcel of a zoo visit, often to the detriment of the animals, A lack of respect for animals. But it has changed dramatically. And I think a lot of it is to do with the profile of zoos. There is a, a greater understanding that zoos have a, a, a serious role to play. I think it’s rather different in, say, in, in Germany for example, where zoos are seen as, as cultural institutions and have been for a very long time.

That’s not really been the case historically in, in the uk. But now we have a very discriminating zoo public. And as people now, they, they want and need permission to come to the zoo. So the zoo has to be a good place doing good things for people to be, feel comfortable bringing their kids to the zoo or indeed coming as you know, visiting as adults. So there, there’s been a real shift in how people behave in a zoo environment for the better.

What issues caused you the most concern during your career and how do you see the future regarding those same issues?

I think, I mean the, the one that I think initially caused me the most concern was that historically keepers were never listened to. You know, you were there to do the grunt work, you were not part of the decision making process or even able to make a contribution that has, in a large part changed in good zoos. It has changed. I’ve seen a lot of good people historically leave the profession because they couldn’t afford to be zookeepers anymore. You know, they were, you know, getting married, gonna have kids, and financially it just didn’t work anymore. That’s changed in many places, maybe not as much as it could. Certainly not in the uk, I don’t think on a bigger issue. I think there are, I mean, I remember the first conversation I had with a, a zoo director and one that I worked for about the potential use of euthanasia. There’s a number of topics that zoos won’t engage with, certainly not outside of a professional audience.

And, and I’ve always been a, a key advocate, both of, of honesty and transparency about what we do. And in particular, if we’re going to manage animal populations long term, there are tricky subjects that we need to grab hold of with both hands. And, and I think the, the, the discussion, the reasons for using euthanasia as a population management tool, I think has been key in, in my time. And I’ve certainly played a role in trying to open that discussion out. A new one I think is dealing with geriatric animals. Historically, you would’ve seen, okay, it’s mass, the gorilla at Philadelphia Zoo, it’s his 50th birthday. And there was a time when animal longevity was a, a a a measuring stick for how well you were, you were able to look after this species or that species. Then it became being able to breed the animal.

That was the, the real measuring stick.

Now we, you know, more recently where okay, right, is the welfare of the animals, is the environment they’re being kept in, is it challenging enough for the species concerned?

But now we have a situation where we are looking seriously at, okay, now, you know, the, I bought a book recently about dealing with geriatric zoo animals and it’s like we’re going backwards. Making every effort to keep old animals alive is actually contradictory to managing healthy populations of threatened species. They’re taken up space, they’re no longer breeding animals. And I think from a welfare point of view, I think it is entirely questionable to keep an animal alive way past its sell by date. And I think the geriatric animal issue, I think that’s, that’s one that hasn’t really been addressed even within the zoo community. So this idea of, of celebrating a, you know, the, you know, our, you know, our hippo is now, you know, 52 years old. I’m not sure that’s a cause for celebration because if that animal was to die tomorrow, I guarantee you’ll find all kinds of problems at the postmortem that we weren’t aware of. And so I think it’s, that’s, I think that’s a, that’s a major issue that has changed and, and how we perceive it.

And certainly the way I perceive old animals, I don’t see it as a good thing. I hope I’ve answered that question properly.

Are are, are there issues that elucidated some of them, are there other issues that you’d like to see zoos address in the future?

I think, I mean, I think the, the, probably the biggest one is that zoos, many zoos get, they talk up their, their contribution to conservation in, in whatever capacity, be it in, you know, breeding programs or, you know, funding research, field research or, you know, supporting a, a protected area in a range country. But most zoos pay not much more than lip service to it. We, the zoo community makes a much bigger contribution than they did historically, of course. But it’s, if you take out the few major contributors, the, there’s a logical society of Londons, the WCS, the San Diegos, the National Zoo in Washington. You take those out the equation Frankfurt Zoo, just to make sure there’s a continental example. You take those outta the equation, then the, the amount the contribution drops significantly, it’s less so in Europe. I think it’s a more of a problem in North America. I think, you know, this may be a question that you’ll come up with later on, but I think one of the issues is, you know, how much we’re paying for exhibits now.

I think the figures are obscene. I mean, and this is something that the, the anti zoo group have, have, have come up with that, you know, well you’re paying, you know, $10 million, which even these days is a, a minimal amount for a new gorilla exhibit.

You know, would, would that money not be better spent protecting gorilla in the wild?

And I used to rail against that line of logic, but now it’s like you, you can create a good gorilla exhibit that is not, that is great for the animals, but doesn’t cost a fortune to create some stage set of the wild. I think it’s, and, and and range countries who see these examples and they try and emulate them and they do it badly because they don’t have the resources, they don’t have necessarily the expertise. So I think that that’s, that, I think that’s a big problem is that to be a good zoo now, or be viewed as one of the top zoos that you have to spend millions and millions. I mean, I remember when, when the, the Bronx Zoo opened Congo and I think it was between 30 and 40 million US. And I remember at the time it was like, oh wow, you know, huge figure. And believe me it’s a great exhibit, don’t get me wrong. But nowadays that figure pales into insignificance with what people are spending on exhibits. And I, I think in the, in the bigger scheme of things, I think it’s a hard one to justify.

And let’s follow up. When a zoo spends multimillion dollars on a gorilla or elephant or a tiger exhibit and critics ask why this money is not used to help animals in the wild.

You say what?

I think that when, if you’re, I mean, and this is one thing that the American zoo community has been much better at say, than here in, in the us And that at that’s raising donor money for these facilities. I think they miss a trick in that you’ve, you’ve got your, your wealthy family who’s, who’s, you know, they’re interested in funding your, your new tropical house or your new grill exhibit or whatever it happens to be. And I think that there is the possibility to, to make them aware that there’s another way of going about this and we can take a, a good percentage of your generous donation and we can put that into a fund that’s, that’s going to support this wild population or is gonna help protect this, this poorly protected area of gorilla habitat. Or we’re going to, you know, provide conservation jobs for poachers who usually make the best park guards ’cause they know the business we’re gonna, we’re gonna fund that as well. And so I think you can do both and you don’t need to necessarily do this hugely elaborate, as I’ve already said, stage set, which is what a lot of these exhibits tend to be. You also have this unfortunate situation where the more natural it looks, then the more restricted the keepers are for providing enrichment. Because if you have this wonderful arctic diorama for your polar bears, you can’t give them a big blue plastic barrel to play within in the pool because it ruins the illusion. And I think that’s a mistake.

And I think it’s also something that where a lot of Z zoo management, they have a disconnect with their public ’cause the public do not give monkeys about having that big blue barrel and that polar bear enclosure. They do care about watching that polar bear trying to kill this big blue barrel in the pool and appearing to have a great time doing it. That’s what the general public want to see. Active animals, not necessarily stage sets.

What do you think about private breeders and, and can they be partners with zoos?

I mean obviously like, like zoos, there’s good zoos, there’s bad zoos, there’s good private breeders or private holders, there’s bad ones and it’s incredibly easy to differentiate between the, the good, the bad and the ugly. And I think for, I mean you, I mean I’m, you know, my background has primarily been with mammals. But you know, having an informed look at how the, you know, the Herpetological zoo community or the bird community works, that having private people involved with some of these programs is often they can actually do better with those species than we have done in the regular zoo community. So I think private breeders have a very significant role to play. There is an argument made that, well it’s all down to one individual and you know, what if that person dies or they lose interest or they go bankrupt or whatever it might be. Well that happens to zoos as well. I mean, you know, the place we were in, we are in now, I mean it came very close to closing in 19 91, 92. So, you know, even these traditional zoos, they, they don’t necessarily have a guarantee of, of longevity.

So you use the resources you have for the time that you have them and to the best of your ability. And good private people, I think are crucial because it allows us to actually expand the sizes of the populations we have as zoos lean more towards the a, b, c animals, the big charismatic stuff when it comes to the, the small and, and interesting but you know, maybe not a big hook for the public. I think that’s when, when private holders really come into their own ’cause you’re able to augment populations. When I was here in London Zoo had win an extensive small mammal collection and, and quite a number of rodent species. And we’d keep, you know, one exhibit colony and then say a mini downs river mouse for example, one exhibit colony, two off exhibit colonies. But then we’d also have relationships with private holders so that we were able to expand the population. ’cause to be frank, not many zoos were managing many downs river mice. So, you know, the private community for us managing a small mammal collection was crucial.

And, but I think it is even more pertinent when it comes to reptiles birds and probably increasingly in vector Brits Is the national park we talked about the wild is the, within Europe is the national park and helping national parks, part of what zoos think about being partners with them.

Can they be partners?

I, I think it depends on the situation. I think as, as we look more and more at returning animals to the wild where they may have disappeared wild cats in Scotland, or a good example, links reintroduction in parks on continental Europe. I think there’s a strong role to play. I think it, it’s, I I think it’s better described in the role that American zoos have played when you look at animals like the black-footed ferret or the California condor. Yes, these animals have, have, you know, extinct and become extinct in the wild bred in captivity. And then been returned to protected areas. So there, there is this, I think, a good, you know, mutually beneficial relationship between good zoos and protected areas within your own country or a neighboring country, or even further afield. I think there’s a, there’s a, that’s an important relationship to have.

Some zoos do it very well. Some zoos, many zoos don’t do it at all. But it’s a, it’s an important one, I think. And the ones that do it well are the ones that we should be looking at as an example. Okay. Right. You know, that’s a big zoo that’s got this relationship with this national park. We’re a small zoo. Right. There’s, there’s gonna be a role that we can play. There will always be a, a role that, that any zoo can play in, in making a contribution to gazed areas, either in their own country or, or further field.

What would you say is a difficult concept for zoos to understand and implement regarding their relationship to conservation?

Sorry, could you ask that again?

What was the most difficult concept for zoos to understand and implement regarding their relationship to conservation?

This is gonna sound a bit more like a hobby horse, but I think when it comes back to understanding how wild populations need to be managed, and as I said, you know, managing captive populations, one runs into the same problem we have. There’s an argument in many western countries about banning the import big game trophies. Now, you know, I’m not a hunter myself. I have no desire to be so, but if you speak to the serious field conservation community, well licensed, well managed big game hunting has a positive conservation role to play. If anybody is well placed to make that argument to the general public, to the politicians, to the decision makers. It’s the zoo community. But the idea of promoting an argument that involves killing animals, most zoos will run away from, nevermind, engage with. So I think that, I think that our, our ability, our, our position within society, the zoo’s position within society to be able to explain conservation, both the fluffy side and the, the side that is hard to get your head around.

It, it, you know, to, to the, the average person killing animals, particularly ones from threatened species seems completely contradictory to protecting them. But in actual fact, there may be a very positive role to play. And, you know, if we look at the disappearance of large mammals throughout the, particularly hoof animals throughout the, the us, a lot of it, the, these populations have come back and a lot of it has been supported by the issuance of hunting licenses and that regulation of hunting. You know, I remember there was a sign in at the Bronx Zoo, it was one of my favorites, that there’s, there’s more whitetailed deer in the Eastern US now than there was when the pilgrims landed. And I think a lot of that is down to the, well, part of, it’ll be down to the lack of carnivores, but a lot of it will be down to, okay, there’s a lot of people that are interested in hunting whitetailed deer. And so, you know, it makes sense to have a large population to support that. And it’s the, the issuance of licenses. There’s areas of, of Kenya, Northern Kenya in particular, people think, well, you know, people go to Kenya to look at national parks, Northern Kenya, the climate is rough in some aspects.

It’s bandit country, it’s high-end hunting that supports conservation in northern Kenya. It’s not a tourist industry. And I think zoos do themselves and conservation a disservice by not endeavoring to explain the, the, the, the difficult, the harder aspects of conservation, particularly conservation in the field that, you know, we, we are the ones that should be turning to the field community and going, it’s all right guys, we’ve got this, you know, we have an audience. We can explain this. And they don’t.

How do he inspires you then to be more active in conservation?

Oh, threats of physical violence. No, I think set the example. You know, there’s, and you know, the, we, you know, we’ve come back to this theme of, you know, the, okay, the big zoos can do this, the smaller zoos have a harder time doing it. So, but I think it’s making more of the examples of the different sizes and complexities of, of zoological institutions and making a big deal about the ones that really are punching above their weight. They’re making that, that conservation contribution, both in the nature of their animal collection and their, their activities beyond their, the zoo fences.

You know, what, what are they doing in range countries?

What are they doing in their own country?

You know, what are they doing for, you know, conservation of species with within the UK or the US or wherever they happen to be?

So I, I think it’s making more of the examples and celebrating those examples and having some kind of mentoring program where, you know, and you know, whether this is something that the regional zoo associations can play at is, right. You know, we, we looked at your, you’re one of our members. You’ve been a member a long time. We’re looking at your conservation contribution and we’re not really seeing something very tangible. You know, we can provide a mentor to maybe help you down that road. ’cause most places will want to do that, even if it’s just to make sure that they look good. They’ll, they’ll want to be seen to be institutions for good that are making a, a, a significant conservation contribution. But some places need to be shown the way.

Does space continue to be a problem for Zeus As alright?

I mean, I’ve been responsible for making polar bears a palatable species for zoos within the UK in particular. And, and a lot of it was to do with space. How we kept that species before in general was appalling. So now we’re looking at a, a very large scale enclosures, you know, measured in, in acres and not square feet or square meters. And I think there are species that where they do need the space, but I think a lot of it can be down to species selection. We have a lot more places that have large acreage and, and can manage species that need to be kept in large herds for all kinds of social reasons. When I was working here in London, with the exception of, of the giraffes, the oke section started to move towards managing forest species like pygmy hippos and the copies. Because managing a forest species in a, a smaller enclosure is simpler, you know, from welfare point of views is easier to meet their needs than say a herd of wildebeest who need large numbers in a large area.

So I think it, a lot of it’s down to species selection. And so go back to a previous question where it said, you know, like, you know, what’s the emphasis I think it should be on people keeping, you know, conservation, important species, threatened species, zoos, waste a lot of space by keeping quite a lot of animals, which are in no at no risk of extinction whatsoever.

So, alright, do we need another meca enclosure?

No, we don’t. Do we need another European enclosure?

Similar sort of social unit, similar sort of lifestyle to mere cats and to the general public. You know, Sue Lake could probably pass for a mere cat, you know, you one can make substitutes, but, so I think the space issue would not be one if we stopped devoting as much space to species that don’t really need our help.

Do you think animals need to earn their keep?

That’s a good one in as much as how things have changed with keeper experiences and whatnot and you know, right. You know, you’re allowed to feed the animals, then you’re not allowed to feed the animals and now we’re charging you extra to feed the giraffes. And so there is a, has been an element of not, so whether it’s the animals earning their keep or just the ability for zoos needing to extract more, to generate more income, I think there should be a reason for every species that is in a zoo. And that reason can be incredibly varied. But being, you know, it’s part of a, a breeding program where, or we’re trying to learn more about this species, we specialize in that particular group of animals. I think, I think every species has to have a, a reason for being in the collection. And, and most good collection plans will have a, a column for justification.

You know, why, why do we have the, you know, why is this species here?

And it may be a common one, but it’s used as an analog for a threatened one that either we’re trying to learn more about them or we’re using it as an example for, from an educational point of view for, for the public.

So yeah, to use your term, do they have to earn their keep?

Yeah, that, but yeah, there needs to be a justification would be the way I would, I would put it.

So what is your feelings about zoo feeding programs?

Well, I mean, I’ll be honest, when I was running the animal department at the Highland Wildlife Park, we we’re ahead of our, our sister and, and more senior partner, the Edinburgh Zoo in starting, you know, keep it for a day programs or meet the polar bear, you know, you know, hand feed the tigers, that sort of thing. So we were kind of ahead of it. We, we used it as a, a revenue generator for buying kit and supporting Scottish wildcat conservation. So I think that there are zoos, I know Chester Zoo, I think they still do it. They used to from all the keeper experiences or feeding the animals, you know, you know, meet the giraffe, meet the tigers, the all the money went into a fund that paid for keepers going to zoo conferences and things like that. I think as long, I think as long as there’s a good justification and it’s done in a, a sensible way, you’re not, you know, it’s not 10 groups of people a day feeding the giraffes, you know, it’s the, it’s the, it’s, it remains a, at best, a once a day, twice a week, whatever it is, activity for that group or that individual or that species.

I’m sure there are some zoos that probably oversubscribe to these activities, but I would like to think that most do it in a sensible way and do people get a lot out of it?

The polar bears at Highland Wildlife Park, we’ve seen people burst into tears, not because they were frightened or anything like that, but they were just so overwhelmed by being obviously with a fence in the way. But being that close to a live polar bear and the, and for us, it, it, it, you know, for anybody that works in the zoo business, you know, you sometimes you have to be brought back to reality that, that what we do is pretty special and the, the exposure we have is pretty special. And if we can, I think, I think we have a, a responsibility to share that novel experience with the general public obvi, albeit in a, a limited way. But it’s also one of the things, you know, good publicity when that family that met the polar bears and burst into tears. And if, you know, they’re at some family dinner or down at the pub or whatever.

And what did you do last weekend?

Oh, we met the polar bear at Highland Wildlife Park and it was absolutely amazing. And they’re doing a great job and the bears are really well looked after.

What better publicity could you want?

What, what better way to get the message across about, about polar bears or the roles that zoos play or whatever, you know, the, the general public had our best advertising tool.

Is there a wild out there or have the majority of wild spaces been turned into managed wild zoos?

I generally use the term mega zoo. I think, you know, people have this illusion still of say, you know, eastern or southern Africa being, you know, this big wild place. And you know, more and more of these parks are privately run, they’re fenced areas, they’re highly protected. There is a need for active exchange of animals from, you know, one protected area to another or one private reserve to another. The few wild places that exist are disappearing rapidly or, or becoming more managed. Obviously, you know, things like climate change is gonna have a, an impact on some of these places will disappear because of of, of what’s happening in our climate.

Will we be able to recreate them, you know, if the the Great Barrier Reef gets bleached over, are we gonna be able to create a, a new bar, great barrier reef somewhere further north or further south?

The, I think one of the most, there was, we had a, when I started here at London, there was an American vet who was on the team Barkley Hastings. And I, I think I’m correct in saying that Barkley was the first vet zoo experience that went out to provide vet support for the wild populations of mountain gorillas in Virunga National Park because of, you know, tourism and, you know, not just snare injuries, but you know, running into respiratory problems because of the proximity of visitors and whatnot. And, and I think more and more the, the skills base that we have developed in the, in zoos is more and more applicable to how we need to protect animals in the wild.

So to go back to my definition of mega zoos, you know, that, that our ability to manage small populations, to transfer animals, the, the drugs that we have developed for dealing with animals up close and personal, just our whole approach to, you know, how do you, if you have to fence an area off, what kind of fence do you need?

So there’s all these skills that we have that we take to a degree we take for granted in the zoo community are increasingly applicable from managing what passes for wild places.

Now How difficult do you think the future for Asian and African elephants in the wild is?

I think that for the African bush elephant, I think there are, because of the, the national parks, I think they’ll, they’ll be need to, they’ll need to be more manipulation of the animals. But I they will continue to exist in what passes for a wild state. I think the likes of forest elephants and Asian elephants, because they’re basically a forest species, I think they’re the ones that are, they’re more likely to be in a lot more trouble. I think there needs to be a great deal more imagination, particularly in an Asian scenario. There’s been a lot of time, a lot of effort spent on finding ways of dealing with elephant human conflict in, in eastern and southern Africa. I think, and and to an extent in India, I think there needs to be a lot more in Asia to, to deal with the problems of stopping elephants going through farms or, you know, creating, you know, ways that elephants can go to traditional feeding grounds without running into problems with people. I think it’s a difficult one, worst case scenario for the Asian elephant, I think you’re gonna be looking again at, at zo areas where, okay, yeah, we have a, a population of elephants and basically it’s contained. I think that will be the sorry, state of affairs with, with, with some exceptions.

That said, and now because I do quite a bit of work in India, I, I was sitting in an airport, I think it, it might have been Mumbai and waiting on a flight. I’m just looking out the window. And here we are in one of the most populous cities, certainly the most populous country in the world. And, and there’s all these birds of prey flying overhead in the middle of Mumbai and a country of 1.4 billion people. And they still have elephants and they still have tigers. More of a problem with leopards coming into urban areas, but they still are able to protect wildlife.

I think, I think India isn’t, is is a really interesting example for other Asian countries and, and maybe, you know, west central African countries to look at and how have they squared the circle of people living in close proximity to big dangerous mammals?

And I think part of it’s cultural, but I think part of it has been, there’s been a real concerted effort to make sure that that is possible. Will it continue to be so, remains to be seen. But I think, I think India’s a really interesting example.

How’s this, would you say zoos or requirements have been in achieving the reintroduction of species back into the wild?

What are the issues? Some examples?

I think the issue is that the list is very short or certainly a lot shorter than it should be. I remember, you know, we, if we were, if we were into an argument with a an anti zoo person, there would, it was the classic, and this would be in the, in the seventies and eighties, and you’d roll off, you know, Arabian orx, European bison, schulsky horses, maybe golden lion tamarinds. And there’s, those would be the classic examples of, you know, here’s where zoos have made a, a very significant contribution and the species have been reintroduced. Or in the case of golden lion Tamarinds, the ca captive population has augmented a shrinking wild population. I think there needs to be more reintroduction. I know that Howlet Zoo or the Aspen Oil Foundation in the UK was criticized initially for sending gorillas back to Central Africa. And I, and I’ll be honest, I was one of those critics, I have very much changed my mind and they are now held up as an example of, of a good protocol for reintroducing gorillas or great apes back into the wild. I think we need to do more experimental reintroduction.

What, you know, the, the classic problems with the golden lion tamarind reintroduction where they were kept initially in enclosures where all the perching was bolted down and when they were released in, in Brazil and they touched a branch that moved, it’s like, whoa, what’s that?

Or they had no fear of snakes. So the researchers following the radio collar of a tamarind that’s already inside a red-tailed boa, we need to, with every reintroduction there’s species specific issues. So reintroducing animals that may not need to be reintroduced, but at least if we can learn how to do it. I think there’s two sorts of reintroduction. There’s ones for good conservation reasons. The, the, the wild population no longer exists or it needs to be augmented.

But the latter is, is more normally the example or once where, okay, let’s find out how do we do this?

How, how, how do you reintroduce a polar bear?

If we get into that situation where, you know, we’re having to return the, the polar bears to a, a reconstituted a arctic, how do we do that?

What’s, you know, big dangerous animal like that.

How, how do we approach that?

I think the Russians have been doing some really interesting stuff with tigers that I don’t think has received the, the focus that it should, you know, reintroducing elephants or big carnivores or big primates, you know, the, the, the, the really complex ones. The ones that are more likely to cause an issue for the local population.

I think those are the ones where, you know, we, we don’t have enough information, but even reintroducing small stuff, you know, can we do it?

Is it easy to do some species?

You open up the books, you let them go job done others soft releases, training, training them to avoid predators. You know, the, I was involved to a degree with the Vancouver Island Marmite reintroduction breeding for reintroduction project when I was working in, in British Columbia. And, and the first animals that we could breed them in captivity, no problem. You know, the first ones that got released, they’d come out of their hibernation chambers and look up and there was a golden eagle overhead and they’d just sit there and watch the eagle as it came down and got them, or the wolf or the mountain lion. And so having to come up with a method for teaching them to avoid predators involve the 12 volt car battery and the taxidermy specimen so that they were negatively reinforced. And that changed the survival rate in the wild black rhinos. Rob Brett, who was affiliated to some degree with Theological Society of London, he was involved with black rhino transfers in Laikipia in Kenya, and they had major problems when they released the rhino and, you know, they would run into conflict with maybe some resident rhinos or they didn’t stay put. And I said, and I was chatting with ’em or I think a beer in the pub, and I said, well, I said, when we get a rhino in a zoo, before you let out the crate, you take a load of the feces out of the enclosure and you put it near the gate so you don’t have as far to walk with a wheelbarrow.

And, and the rhino will continue to defecate on that location. I said, you know, you’ve got these rhinos you’ve soft releasing them from, from Bomas. Yes. And he went, yeah. I said, right, well then, you know, collect up all the shit and then redistribute it out. So when the rhino gets released, it’s got a familiar smell and that chain both the interaction between the resident wild population and these transferred animals and the, the ability for the animal to stay put and not just go wandering off. So, so yeah, that, that crossover of technique.

What do you think are the major differences between zoos in North America and those in Europe?

How we feed our animals for the kickoff and specifically carnivores. I look at North American carnivore diets and it just makes me want to cry. I have seen an adult tiger virtually inhale, its minced meat diet. Whereas, you know, we, and you know, we’ve always fed them actual meat on the bone joints, more increasingly whole animals. And it still tickles me that, oh yeah, another research project into how, you know, feeding carcass, carcass feeding for large carnivores. And it’s like, what really we, we have to go through that exercise one more time. And again it’s, you know, marketing types going, oh, well you can’t do that in front of visitors. I mean, I remember here in London, I I hung a, a big white rabbit.

It was dead off a bungee cord for the servs. And, and the visitors were about 10 deep at the windows watching this rabbit getting torn into pieces by the cerebrals when they used to, when they once a week feeding in the reptile house here at London Zoo, I think it was every Friday afternoon they used to do it. And you know, you had to get to the reptile house an hour or two beforehand, otherwise you would never get into the building. It was such a popular activity. So this idea that that zoo visitors will be repulsed by feeding carnivores actual animals is a bit bizarre and actually unfounded. I think if they, if television stations brought back live gladiatorial combat to the death, it would probably be the most popular program on television. The fact that unfortunately, and this is a, a problem that we don’t seem to be learning in Europe, is that a number of of breeding programs have collapsed in America because of the widespread and in judicious use of contraception and breeding control. And then when they want to breed from the animals again, they’re not able to.

And so, you know, the, the program gets augmented from, from Europe where we have been less inclined to do that. But, you know, I see issues with, I’ve been helping a couple of zoos with, with breeding and, and introduction of lions for breeding. And I’m thinking having to help zoos show them how to breed lions or how to do a lion introduction. It’s this is, this is cat keeping 1 0 1 breeding moratoriums, which again, have been more prevalent historically in America than in Europe. And the staff changes, the older keepers leave, the new ones come up and then they have no experience of how to breed this species or that species. And so the wheel gets constantly reinvented. There’s always a situation where the people say that, you know, whatever’s happening in America eventually gets over here. And un unfortunately with the, the zoo, I think some of the negative aspects or or what I perceive as, as, as negative aspects of how animals are managed in North American zoos coming over here and causing the same problems have, have we not learned from these mistakes.

So I think there’s that, I think there’s, again, there’s the, if it, if the enclosure looks natural, then it must be good for the animal when in actual fact, going back to something I’ve said previously, it’s basically a glorified stage set and not necessarily good for the animal. I think there’s more attention to appearances than purposes. That’s, this is an incredibly broad stroke criticism of North American zoos and, and certainly not all are guilty of it and most do some things really, really well and better than anything in Europe. Other thing, other stuff maybe not so much and vice versa. And so I don’t want to appear too critical of, of my American colleagues who I in in general have a reasonable amount of respect. For Recently there have been some zoos requesting donations of pets to feed their animals your comments. I I I love the Danes for their boldness. I really do. In, in Denmark where this has happened, no one blinks.

It’s not an issue. I actually recently my wife and I made the decision to euthanize our dog. Obviously the body did not end up being used as food for a zoo animal. But I think a lot of it comes down to making that, being able to make that decision and what’s actually gonna happen to the animal. Extending on that is that I did a, a paper for a zoo journal and it was entitled Tigers Don’t eat meat and they eat animals.

And this is something that certainly in the west, we, for the many people that that disconnect now, you know, where does milk come from?

It comes from a, a carton or a bottle. It doesn’t come from a cow anymore in many people’s minds eyes. So the fact that that animals eat other animals is something, again, is another discussion point that zoos have failed to explain to the, to the general public. And so, so a story like that, when it breaks the reaction from outside of Denmark is short quarter, but then no one’s getting their, as we say over here, their knickers in a twist over some no named cow that goes from a farm to an abattoir, gets chopped up and then gets shipped to a zoo for feeding the lions and tigers.

I speak to zoo people about, well why, why are you controlling breeding in your, your deer and antelope?