Okay, I’m Dr. Gordon Hubblle. I was born and raised in the west side of Cleveland suburbs, born in Lakewood, raised in Fairview Park. And I went to college at Ohio State studied veterinary medicine. Actually I got my interest in wild animals I guess, back in junior high school. ‘Cause I was the kid on the block that took care of all the injured wildlife. And then when I was in junior in high school, we were assigned to write a theme about what we wanted to become someday. And I had no idea actually back then. And my dad suggested that I interview a friend of his in Rotary who was a veterinarian.

And so I went down and interviewed him and quite by coincidence, he was also the part-time vet at the Cleveland Zoo. And so after I interviewed him I thought that’s pretty neat. I wrote my theme. I wanted to be a veterinarian. And then I went back and volunteered at his animal hospital. And the dogs and cats mainly, but occasionally a zoo animal. Well, let me back you up just a minute.

What was your birthday?

Oh, I was born February 28th, 1935.

And when you said you were doing animals or taking care of them in the neighborhood, were you collecting animals when they were sick or people were bringing them to you?

How’d you get that interest?

People just brought them in to me. It was usually a bird with a broken wing or something like that. And quite often the animals that we got were not salvageable. They just were so far gone that they didn’t survive. But it was interesting anyway, taking care of these animals and tried to pull them through their ailments.

Were you a kid who brought snakes home?

Yeah, and bats too. I loved bats when I was a kid, and we knew an area where there was a big tunnel under the road that big brown bats used to hibernate in the winter time. So I would go down there and pull a couple off the wall and bring them home, warm them up. Let them fly around the house, and feed them ground beef and cheese for a few days, and then take them back and let them go back into hibernation again. Snakes have always been an interest of mine. I used to collect snakes up there. Of course we didn’t have to worry about poisonous snakes ’cause there weren’t any in that particular area. But yeah, I think they’re interesting animals.

What’d your parents do?

My father was a commercial artist, a rather famous one. He painted aviation pictures. He was commissioned each year to go out to Cleveland National Air Races and take pictures of the planes that were qualifying and then paint a painting of the winner. And during that time we got to know the pilots and the planes and I’ve seen several planes crash out there. In fact, one time we were out there when a P-38 was qualifying, and we noticed that he didn’t come around the second time, ’cause the course was fairly large. We could only see part of it. And then all of a sudden there’s a whoosh over our heads and this P-38 sailed over our heads, and out over the Cleveland Airport. And he couldn’t put his laps down.

This one engine was on fire and so he couldn’t slow down. So he flew around the entire airport, probably about 10 feet off the runway trying to slow down. And finally belly landed right in front of us. And the airplane slid across the runway into a fence and he jumped out, ran down the wing and the thing blew up. Wow! Saw P-40 crash out there, in the middle of the railroad station on west side Cleveland and also an experimental plane. They had a research plan out that the federal government did at the airport, and they experimented with different kinds of planes. And this one plane had the engine behind the pilot and they’d had problems with them before and they just happened to be looking out the window, and this thing flew over and it was on fire and it blew up.

So you were exposed to airplanes at a young age. Oh yeah, we used to go out and fly almost every weekend.

Did that peak your interest that you wanted to be a flyer?

No, not at all. And today I really don’t enjoy flying that much (chuckles). Now you indicated you had to write a paper and you interviewed veterinarian. That was the spark that you thought, wait a minute, this is something I’m interested in. That was the spark that got me interested in veterinary medicine. And then as I got into college, I got a part-time job as a keeper at the Columbus Zoo, working weekends. And that’s really what solidified my interest in zoo animal medicine. And when I graduated in 1959, of course there were only, I think six full-time veterinarians in the country in zoo work.

And I rode around to different zoos and they all said, no (indistinct). The second year, well, I went off into practicing in smaller practice in Cincinnati, but I worked for the fellow who was the part-time veterinarian for the Cincinnati Zoo. And he was an alcoholic, and didn’t show up for days and in at work. So when the Cincinnati zoo called, then I got to do the work there and I enjoyed that. Well again, let me back up. You were a part-time keeper and you were going to school.

And so on the weekends, how’d you get this job as a part-time keeper at the Columbus Zoo?

I think mainly through Warren Thomas, who was working there. Had worked there for several years. And I can’t recall exactly, I know I went out and applied for it. Talked to Earl Davis, the director of the zoo. And Earl was an interesting guy too. A politician, he was really not interested in the zoo or the animals at all. Spent every afternoon or the neighborhood bar drinking. But anyway, he had the good sense to hire me as a part-time keeper.

And what did you do as a part-time keeper?

Well, (chuckles) the first day I came in, I was told to report at six o’clock in the morning and it was pitch dark. It was March, 1960. Let’s see, no 1957. And the head keep there, gave me the keys to the birdhouse and he said go over to the birdhouse, and the keys will unlock the back door and just go and wait till the keepers arrive. And so I did. A cold, windy and I went over unlocked the back door. It was pitch dark, and opened the back door and a voice yelled out, “Shut the door bub.” And I thought, wow, somebody here. So I fumbled around, reached around, finally found the light switch, turned it on.

There was nobody there. So I walked all through the building and there was nobody in the building (chuckles). And I came back and I noticed there was an African gray parrot sitting on a perch right by the back door. And he apparently was the one that said that. I worked at the birdhouse there for two years. And that bird never said that again. He said a lot of other things, but he never uttered those words again. Which was kind of amusing.

I also did little work in the reptile house, and some of the other parts of the zoo, but mainly the birdhouse. So you had a relationship with (indistinct).

Warren Thomas was the veterinarian?

No. He was a student. He was in my class, and he had worked there as a part-time keeper. So you’re both there as part-time keepers. Yeah. Okay.

And then how long did this part-time job last?

Well, it lasted a couple years until I graduated and then went down to Cincinnati to work in a small animal practice, doing the zoo work part-time.

Now was this your own practice or you were working for someone?

No, I was working for somebody else. Yeah, I remember one of my first escapades out in the zoo. We got a call one morning at I think… Well I went into work at nine o’clock in the morning, started treating the dogs and cats. And we got a call from the zoo at 9:15. The head keeper there stated that their new snow leopard was sick, had eaten some rotten meat, looked like it was dying. Would I please come out and save its life. Well, (chuckles) I was just fresh outta college.

I didn’t know a whole lot about zoo work, and the snow leopard was the most expensive animal in the zoo. At that time, it cost $3,500. More than an elephant. Three times as much as an elephant, as a matter of fact. So I packed up a little kit of instruments and drugs and went out there and drove in the service road, and out on the main road and pulled up in front of the cat house, and the animal was inside. So I went inside. Well, since it was such a rare animal, not only was I zoo director there, the head keeper, several curators, but most of the zoo board was there and the president too. They all wanted to see me work on this animal.

I went into the public walkway and the snow leopard was sitting near the back of the cage. And he was paralyzed in his back quarters, but could move his front quarters and lift his head and snarl. So I went around the back at service road there, and reached through the bars and grabbed him by the tail and pulled this 125, 140 pound, I don’t know what it was. Cat right up to the bars, gave him a shot, I think of antibiotics. And another one of course, and I thought, well, I gotta do something to get this, whatever he ate through him. So I thought I’ll give him an enema. And I brought a little enema can, which is a little can maybe a little cord of water. And it had a tube running out from a spout in the bottom of it.

Something that we used to give enemas to dogs, but it was just too small for this big cat. So I looked around and I noticed that they used high pressure nozzles to clean out the cages, which had small (indistinct) on them. And I thought, okay, I’ll just use this thing to give the enema and greased it up with KY jelly and inserted in the back of the cat. And I told the keeper to turn on the water very slowly. Well, all went well for about a minute and quarter of a minute and a half, something like that. And all of a sudden there was this explosion (chuckles) of the most awful smelling fecal matter you could imagine from out the back of that cat. Just covered me from head to foot. Well, this was also the day that I had to go to the hospital to pick up my wife, and newborn son (chuckles).

And I had to be there at 10 o’clock, and it was now quarter to 10. Fortunately the hospital was not far away, but I was a mess. And of course everybody was got a big charge out of me getting covered. All the board members and everybody. But anyway, I went to the back of that cat house and took out my shirt, and washed up as best I could quickly. Remembered I had a grey plastic rain coat in the car. So I went out to the car, got the grey plastic rain coat on, and this hot June day in Cincinnati, and drove over to the hospital. And I’m thinking, well, I can still pull this off, ’cause I’d just go up to the emergency room door and they’ll bring my wife down.

But there was a rule at the hospital, that I had to go up to the floor to get her (chuckles). So I did, and I remember the shock look on her face and she says, “What’s the matter?” And I said, don’t say anything (chuckles). Let’s just get outta here. So we left and went home and I got cleaned up for good. But the good thing was that the cat survived, the snow leopard did well. And this was when you were part-time vet- Part-time vet, yeah.

And you were part-time veterinarian because the- The guy- They got full-time or they didn’t?

No, they didn’t have a full-time. There were only six in the country at that time as I recall. Pat O’Connor, Les Fisher, I forget where else the other ones were, but there weren’t many.

So the Cincinnati Zoo approached you to be the part-time vet?

No, the guy I worked for was contracted to be a part-time vet at the zoo. And I was working for him, but he didn’t show up for work. So it was up to me. In spite of all that I still was interested in zoo work (chuckles).

So did you become kind of the go to guy that they would call, or that you only filled in when he wasn’t?

I filled him when he wasn’t, but it got to be that I did just about all the work. If he got a call and he’d send me out, or if they had something that needed to be necropsy they’d bring it over, and I’d do the necropsy on it.

Were you able to then communicate with these other part-time veterinarians, or other veterinarians in zoos?

Yes. What we did was, I remember coming to Chicago to meet with Les Fisher and I think Pat O’Connor was there. I don’t know if anybody was there at the time, but we decided that we had to communicate with each other so that it would help us in treating these animals. And so when we would get a case that was interesting, we’d write it up and mimeograph it back then and send it out to each other. So we sent packets of case reports out to each other on a routine basis. And if we had a problem, then I’d call Les or Pat Connor or somebody. And I’d say, this is what I’m faced with.

What would you do in this situation?

What have you done?

And that was really the beginning of the zoo veterinary association. So when you were doing this, were you thinking, I want to get out of my dog and cat practice and I want to do full time at the zoo, or were you happy with what you were doing with this part-time. Okay, I was not happy working in some animal practice because it was too routine. Fecal exams, dermatitis, (indistinct) where almost all the surgery we did. Diarrheas and things like that. It just got to be too routine. And I didn’t like the routine nature of it so much. With zoo animal practice, when I came in the morning, I didn’t know whether I’d be working on a python or an ostrich, or a giraffe, or an elephant or whatever.

And to me that was challenging. I enjoyed that kind of work. And so you were kind of thinking, I need to figure out how to do this full time. Yes, and I rode zoos around the country for two years in a row. I actually got a call from George Vierheller out to St. Louis Zoo and I went out there and interviewed him. And then he decided at the time that he wasn’t gonna hire a vet. I don’t think he liked vets anyway (laughs). And then I finally got a call back from Crandon Park Zoo in Miami.

And they said they were ready to hire veterinarian. So I flew down for an interview and we decided we would move down there. And moving from Cincinnati to Miami, Florida was like moving to a different country. It was quite a change, quite an adjustment, but we really enjoyed it down there. So was it a difficult decision, or the minute they said, we’re interested, we want to hire you. There was no thinking. It wasn’t difficult at all, no. Tell us a little about this zoo that you arrived at.

Maybe a little bit of the history, and what was it like when you got there?

What were your first impressions of who was the director?

Some general impressions. Okay, well, the Crandon Park Zoo is located on Key Biscayne, in the Southern end of Grandon Park. 25 acres of zoo. It started back in 1947 when a traveling road show, animal show, disbanded and they sold their animals to Dade County. Metro-Dade County. There were a couple monkeys, a green monkey, a rhesus monkey, two black bears. There was one other animal there too. But they put up some temporary cages on the beach and kind on park.

And then in 1948, they built a causeway across to Key Biscayne. Up until then, the only way you could get over there was by boat. I don’t think they had a ferry even. And they opened a zoo there. Now the first zoo director that they hired, her name was Julie Allen and she eventually married Henry Field. So she was Julie Allen Field. She was a lion tamer in a circus. And so she brought her lion and tiger act to the zoo and built a mound of where she could do her tricks and things.

And that was the way Crandon Park Zoo started. And it kind of grew like topsy, it just once they got a little money, they’d add another exhibit. There was no rhyme, no reason the way that it was laid out. But then Julie Allen Field left, I guess under questionable circumstances. And Bob Matlin was hired. And Bob eventually went out to Phoenix as the first director of that zoo when it was built. But Bob was a good guy to work with. And we did fine together, but he was there six months and then he quit and went out to Phoenix.

So at the ripe age of 26, I was appointed zoo director. And this was a different ball game. I’d been in private practice. And the method of operation is all together different when you’re in private practice. If you want something, need a instrument or something, you go out and buy it. But with county government, you requisition it, it may or may not get approved, and it may be six months to a year before you get it. And that was one difficult thing. Personnel was another thing.

I really didn’t have too much say over the keepers that we hired, as they were sent to us by the parks department, were a division of the parks department. And that was frustrating too. So it took a while for me to adjust to the whole operation out there. Well, now you were hired as a full-time- Full-time veterinarian. Right. You were practicing six months approximately as the veterinarian under the director, and all of a sudden he leaves.

Did they automatically say, you’re our guy?

Did you apply for it?

Was this something you aspired to?

How did that- Okay, they automatically said… They came along and said, you’re the man. We had a head keeper at the time Wayne Homan. Wayne eventually went out to Phoenix too with Bob Matlin. And he was good about… I mean, he was really in line to become the director, but the parks department director thought otherwise. But he was good and we worked together fine. So when they come to you and say, you’re the zoo director, is this something you say, oh my or you say, great.

Yeah, no. I said, yeah, I’ll do it. I wasn’t really prepared to do it emotionally I guess, at the time. But yeah, I’ll do it. I didn’t jump up and down and yell and scream or anything. But yeah, it was an interesting challenge and I like challenges.

And what was your biggest surprise?

Was it the bureaucracy that was your biggest surprise, or other things when you first got into the job. The biggest surprise, well, the biggest frustration, I guess, was the bureaucracy. I had never been thrust into a political situation like that before, and it was political for sure. But we got along well. You know, back in those days… The word zoo starts with Z and it’s the letter in the alphabet. And it’s the last thing in the budget. And so to get any money at all for the zoo was really tough.

Anything for capital improvements, they’re almost nonexistent. And that was difficult. We had to fight for everything we got (chuckles). Let me ask a question about your time as a veterinarian, the short time.

When you were veterinarian, how did the keepers receive you your full time now?

How did they receive this new person and what was your relationship with them?

Well, the keeper crew was interesting. Of course, back in those days, they were not professional by any stretch of the imagination. A lot of them were farmers and they just simply did their job, and came in at eight o’clock in the morning did their job and left at five, or even a few minutes before if they could get away with it. So there was just somebody else to work for. Really didn’t have too much problem with them.

Were there curators at the time running the collection when you started this veterinarian?

No, we had one head keep and that was it. We had a bird man who was very good, an older fellow. He had a green thumb when it came to raising waterfowl. And for that reason, the feds sent us a pair of trumpeter swans to set up in a captive breeding situation. The only problem is they sent us a pair of females and that didn’t work out. So we badged the feds for a couple years after that. And finally, they sent us a male and we sent the female back to them. But the trumpeter swan being a big bird and requiring a lot of room to take off.

We put them in a pen that was a chain link pen, went out to the water and back along the backside of the water. But we didn’t feather clip them ’cause we knew he couldn’t take off from that pen. But trumpeter swan being a big, powerful bird, he tore a hole in the fence. Worked his way over a couple of exhibits. So there was enough for him to take off. And he took off one afternoon. One Saturday afternoon. Well, we knew we had to notify the feds, but it was a weekend.

So we decided we’d wait till Monday ’cause we didn’t know how to get ahold of him. And that evening we found that the trumpeter swan was roosting over in a dump on the other side of Key Biscayne. So we had the bright idea that, okay, we’ll sneak up on him at night. You know, he can’t be very awake at night, and they don’t fly around at night well. We snuck around two AM and we didn’t even get close to him. He took off and flew away. We didn’t hear from him on Sunday. And then Monday we got a call in the morning from a lady in South Miami.

She says, “I’ve got this big, beautiful white bird in my backyard “and what is it?” So she described the trumpeter swan perfectly. So we said, don’t do anything, just leave him there. She boarded on a canal. So we could land in the canal and walked up into her backyard. So I took my head keeper and we went down there, pulled into a front yard, and walked into her house and looked out the picture window in the back. And there was our beautiful swan. So we decided what we would do, would each run around the house one side and I’d take the other side, and jump on him before he could take off. And while we were there, he stuck his head under his wing, went to sleep.

So we ran around the house and caught him and held him down. So we didn’t have to make that embarrassing call to the feds about their swan getting loose. First thing we did was clip his feathers and we never were successful at breeding him because we really didn’t have enough space to breed swans. We breed a lot of waterfall, lot of ducks and geese, but not swans. Now you mentioned Bob Matlin was director, when you first started this veterinarian.

What was your relationship?

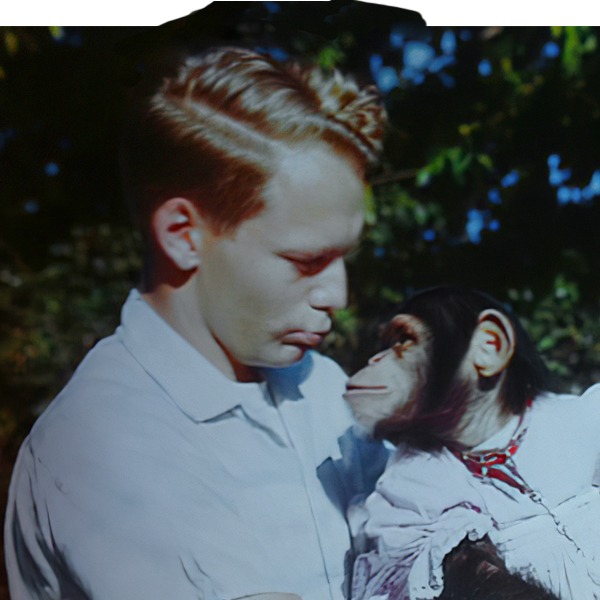

Did he say do your thing or was he- He was very supportive. Interested. Yeah, do your thing. But he was interested in things, and we talk about different problems. Yeah, he was very good. One of the first problems that we had, and that leads into another interesting story. We got a chimpanzee from West Africa, a young one. And we had her, I think three or four months.

We actually would quarantined her. But then we had a couple people come down with hepatitis, and it ended up that five people came down with hepatitis. So we called the CDC and they sent a fellow down two fellows down actually. And anesthetized the chimp and took a biopsy, liver biopsy, and sure enough that’s where the hepatitis had come from. And the five people, the four of them had a very mild case. The fifth one was in the hospital for a couple days, but no lasting effects. But the interesting thing that did come out of that is when they anesthetized that chimpanzee, they used a product called sertraline (chuckles). And sertraline was fantastic.

I mean, you could give a shot intramuscularly. There was no excitement period. They just simply got sleepy and laid down, went to sleep. The one thing we did notice is that they would do a little yelling and screaming now and then while they were under. Well, sertraline had been a drug that had been experimented within people and prisoners, and they found it was hallucinogenic. So they stopped using it on people, but Parke Davis kept producing it. And we used it in zoo work, and we got all the sertraline that we could use to experiment on animals. And we used it over a thousand times, and never had a death from it.

Never had any problems with it. And we used it on everything from big cats to primates. We even used it on hoofstock crocodile. It was wonderful for crocodile. Never had any problems with it. But of course, sertraline is PCP angel dust, and became a controlled substance and they finally stopped making it. But it was one of the best anesthetic agents that we ever had to use in zoo animal medicine. They put a derivative called ketamine on the market and it was all right, but not like sertraline.

It was good. We used it up until the time I retired.

How were you administering these drugs?

Intramuscularly. And that was the beautiful thing about it. ‘Cause the only way you could give it to some of these animals was with a capture gun and the projectile syringe. And the capture gun of course was developed by chemist by the name of Red Palmer in Georgia. And we got one that was in the mid 1950s. We got one of his first ones probably around 1960, 61. Just about the time I got to the zoo. Was a unique device, ’cause it was just more than a air pistol that had an enlarged bore barrel put on the top of it.

And it fired a projectile syringe, which was an aluminum tube thread on each end. Had a needle on it, screwed on one end and the size of the needle depending on what kind of animal you’re gonna use it on. And then on the middle we put a rubber plunger, and there was a little powder charge slipped in the rubber plunger. And then we screwed a TL piece on that. So the theory was that when the thing hit the animal that the hammer in the powder charge would overcome the spring that held it back and it would hit the powder and explode, and inject whatever was in front of it, into the animal. This worked pretty well except sometimes it’d blow the end off the syringe, and it’d come flying back past my head. So they started making the syringes outta heavier material. The first syringes they made, they used a chemical reaction and it just didn’t inject fast enough.

If you shot a chimpanzee, for instance, with it, the chimpanzee would rip it out, and throw it back at you before the thing even discharged. But with the powder charge, it got the dose right now and it worked well, and we used it on a few escaped animals (laughs). So you were really on the pioneering end of using this delivery system for animals. Yeah, we were. And sertraline, ketamine were the drugs of choice that we used. They had experimented with the paralytic agents like succinylcholine, even nicotine sulfate before that. But the problem with them is that the dose varied from animal to animal, from situation to situation. You could inject an animal in the morning and in the afternoon it would take half the dose, or maybe twice a dose.

And so you just kept injecting until you got the right dose. And there were a lot of deaths with it. It just didn’t work out that well. And of course the animals were paralyzed. They could still feel all the pain, they just couldn’t react to it. So it was not a satisfactory method to use anesthetic agents. We didn’t have any intramuscular agents up until thiamine came along. ‘Cause what we were using barbiturates and they had to be injected intravenously.

If you injected intramuscularly, they caused too much tissue damage. So now you are a new zoo director, looking for a challenge.

And what was your day like?

Were you still the veterinarian?

Yeah, in the first year I worked 364 days (chuckles). It tells you what my life was like. And we did manage to start taking a couple weeks off now to go to Sanabei Island. But it was work all the time. Fortunately, we lived about a half a mile from the zoo. I either walked there or rode my bike there. Rode my bike there, but it got to be embarrassing. Sometimes people would stop and ask me if I wanted a ride, if I was walking or even if I was riding a bike.

And my neighbors all felt sorry for me, I guess, but it was a good exercise. And what surprised you about the job as you were doing that on a day-to-day basis. Oh, nothing really surprised me. I mean every day was a kind of a surprise ’cause I never knew what animal I’d be working on. But nothing too surprising there, I guess. I’ve always believed in a lot of public relations things. I always kept a collection of small animals to take out to schools, and we had the children’s zoo and we had animals there. Tame animals that we let the kids touch.

Well, way back in Cincinnati, for instance, we got a call from a local station, a local TV station. That was the educational TV station. And they wanted somebody representing the zoo to bring an animal out for their children’s program. So they called my boss and he said, “Well you do it.” And so I said, okay fine. So at the time we had a few skulls of animals and I thought, okay, I’ll take these skulls out and we’ll show them to the kids. Let them touch the teeth, tell them how they chew, and what they feed on, and all that. And so it was a half hour live show, and I went to the studio and there was a lady moderator there. And it went real well.

The kids were… Young kids that age are a joy to work with. They would ask all kinds of questions, and everything was ooh and on about, oh this eats that or look at the teeth on that. Well, after the show, the station manager came down and he said, “Hey, you did so well, I’d like you to come back next week.” So I said, okay, reptiles have kind of been an interest of mine, a hobby of mine. And I knew the guy who was a reptile curator at the Cincinnati Zoo. And I felt I could be easy enough to borrow some reptiles and bring them to the show. And the lady moderator said fine, that’d be fine. So the next week I went to the zoo and I picked up some animals.

I had a small crocodile, couple lizards, a couple of snakes, a turtle. And went into the station and walked into the room. and there were no kids.

And I said to the lady moderator, what happened?

She said, well, we couldn’t get the bus to bring them out today. I said, oh my gosh. You know, I know something about reptiles, but I haven’t studied about these individual animals. I was relying on the kids to touch them and see that the turtle had a hard shell, and the snake skin was smooth and dry. And I said, you’re gonna have to do that then for the kids so we can carry on a conversation. She said, fine. Well, I opened the first bag and pulled out a six foot boa and she let out a scream and went running outta the studio. So I had a half hour show to do by myself, that I was not prepared to do.

And it was a disaster. But in spite of that, I still later on kept doing them anyway (chuckles). Oh my, that was my introduction to doing live animal shows.

And were you doing things like this in Miami when you were director?

Oh yeah, we did a lot. In fact, I was doing two regular children’s television shows weekly shows at the same time. And then did annual shows for the Ottoman society, all using live animals, all on television.

Now, did you have a vision of what education would be like at the zoo when you took over?

Well, I felt that education was the main thing for zoos. Sure, they were entertaining, and sure some of the bigger zoos could do research. Conservation, yeah. But back in those days, conservation wasn’t a big topic in zoos because animals were readily available. If lion died you just ordered another one. There were animal dealers in this country that could supply them, and there was just no problem getting animals. And I knew all the animal dealers in Miami being a major point of entry. We had animals readily available to us, and I got to go down and pick what I wanted actually.

So there was no problem getting animals for the zoo. And we didn’t really think about education or about conservation. Education, yeah. I’ve always felt strongly about that. And we did develop an education curator position, and had him go out to the schools. I had been doing it up until that time, and take live animals out there and talk about them. So education has always been my main focus, I guess, in zoos. Let me follow up on a couple of things.

Were you able… You said you hired an education curator.

When you came in, were you able to hire other curators or people that would assist you other than a senior or a zoo manager?

The zoo was small. Back then it was 25 acres, and we didn’t have that many animals. Now we did increase the collection and increase the exhibits. So it got to the point where we did have to hire a education curator. And we developed a curator, mammals curator, birds. They were not PhDs or anything in zoology, but they were management people, that could manage animal collections. You mentioned animal dealers and Florida was a hub of animal dealers.

Can you talk a little more about that?

I mean, who were some of the names that you had to deal with and how did they operate?

And you were right at the epicenter. Yeah, Bill Chase was the first one that we dealt with. Charles B. Chase was the name, but he went by Bill. Bill did mainly zoo animals. And was a good honest person to deal with. I liked him very much. And I think his company was called Charles B. Chase. But then we had the pet farm, which was Norman Crowley.

And they did mainly importation of animals for pets. Ralph Curtiss worked for him for a while. And then Ralph went off on his own. He couldn’t stand the pet trade part of it. And we dealt with Ralph. Ralph was a very honest, very good person. He really took care of his animals. But the pet part of it, oh my god, it was awful.

I’d go down there at times when they import a couple thousand monkeys, and a thousand would be dead. It was just… Really it was depressing. And one of the things that got AAZPA and the endangered species mode was the orangutans problem. And I saw orangutans come in there. And again, you get three or four orangutans, half of them would be dead. And the others who would die within a few weeks. And we finally in the zoo profession said that’s enough.

We shouldn’t be bringing these animals in for pets, and maybe not even for zoos anymore because we could breed them in zoos. But especially the pet trade. And we developed our own restricted list, our own endangered species list back in 1962. And the orangutans was the first thing on that list. And we asked the federal government, if they would develop an endangered species list and institute regulations to control the importation mistake. Don’t ever get to federal government involved in anything, ’cause they’re gonna screw it up. And they did. They really messed this up.

We went after them for 11 years, to pass an endangered species act. Finally in 1973, they passed it. And the way it was written, it would’ve put almost every zoo in the country out of business. They listed endangered species. And I swear they must have had kids right outta high school, to write up these lists. But things like tigers, for instance. Tigers were common in zoos. Sure, they were diminishing in the wild.

But the way the endangered species act was written, we could not move a tiger. We could not sell or send off on a breeding loan captive bred tigers to other zoos. If we had an old tiger was dying, we couldn’t euthanize it, without a permit from the federal government. The permits back then took an average of nine months to get. Any place from six months to a year, I guess. But nine months, well. Nine months is suffering for an animal that’s old. I mean, that’s ridiculous.

And of course the cubs in nine months were pretty good size. So it was unworkable, and the AAZPA and their wisdom hired George Steele, who was a lobbyist. Worked for (indistinct) and also an attorney. And he was stationed in Washington. And he worked with the feds and it took two years to get that straightened out so that we indeed could send the captive bred, endangered species off to other zoos, not to private breeders or as pets or anything like that. But it changed the whole philosophy in the zoo world. Because now we realized that we had to start breeding these animals and not rely on them being caught in the wild and imported for us. And that’s when we got into the captive breeding programs and geez, we did everything eventually in the embryo transfers, and artificial insemination and everything.

And eventually we did such a good job of it. We didn’t know what to do with all the surplus animals. So when I left the zoo field, 22 years ago, half of our animals were on some kind of birth control. Either they were all male herds, or we kept the males, female separate, or we implanted hormone in some of the animals stopping from cycling. But we had to do something. We didn’t know what to do with all the animals. Now you’d indicated that you hired an education curator. Were you able to hire a veterinarian to replace you and- We did.

Yeah, I had been zoo director and veterinarian for three years and then we hired another fellow as the zoo veterinarian. And that took a lot of burden off me, although I was being cut off from what I really liked to do and into the political part of it still it had to be done. He was with us, three or four years. And finally he went down to Venezuela to work a private animal farm down there. Wild animal farm. And once he got down there, he was there for a couple years and wanted to leave. They wouldn’t let him leave. And he was essentially held captive in Venezuela.

His wife and kids were able to come back, but he snuck out of there in the of dead night one time and made it back to this country. But, (chuckles) he had a wild time down there. Now we were talking about tranquilizers and doses and so forth. And you were on the cutting edge. Can you tell us the story about the gorilla named Colonel. That’s a chimpanzee. Oh a chimpanzee. And the Jaguar.

And the Jaguar. Colonel was a chimpanzee that somebody raised as a pet. And so he was totally screwed up psychologically. We’d try introducing females with him and he was just scared to death of them. And he’d run and hide, and scream and all that. But he was a big animal. Weighed 146 pounds. That’s a huge male.

And, (chuckles) one day I was sitting in the office and our head keeper came running into the office this Friday afternoon. He said, “Colonel’s out.” And it took a few minutes for me to figure out what Colonel was. And then I realized it was a big male chimp. So I said, okay, you watch him see where he goes, and I’ll get the capture equipment ready. And we’ll see where we can catch him. Well, at the time we had the other full-time vet and he was off that day. So I didn’t know where he kept all the equipment. I went in there and fumbled around, found the darts, the syringes and the drugs.

And by that time we were using ketamine. We weren’t using sertraline. I wasn’t familiar with it. So I did a quick brush up on dosages, and I loaded up three darts figuring I could miss him a couple times, but the third time I better get him (chuckles). So I got into zoo station wagon, and I asked the head keeper where he’d been. He said he went over to the front gate, and he was sitting up on top of the stanchion of the gate, a seven foot high fence. So I drove over there and I drove off so that the driver’s side of the station wagon was facing him, but I hid the capture gun. ‘Cause I knew the minute he saw that he’s gonna take off and run.

So we did a stair off for a few minutes. He was trying to figure out what I was doing there. And I was trying to figure out how I get a shot at him. So finally I told my head keeper to go over in the parking lot. Behind him, well, not directly behind him, but off to the side and yell at him. See if he could get him to look that way. But don’t get behind him, ’cause I didn’t want to hurt hit with the dart. So he did and Colonel snapped his head around, looked to see what was going on over there.

And I shot him and hit him right in the thigh. And he of course pulled the syringe out immediately and threw it back at me. But he didn’t run. He stayed up there, which surprised me. And after three or four minutes, he started getting a little groggy, and it was a call. A small (indistinct) palm that was right next to the fence. And he grabbed a hold of that thing and twirled on down to the bottom of the ground easily. So we picked him up, and put him in the back of the station wagon.

And I drove back over to the exhibit. In the meantime, our secretary had gotten a hold of our vet, our full-time vet.

And he came out, met me at the exhibit and he said, “What happened?

“I thought somebody apparently left a lock off, “or he broke it, I don’t know which.

“What did you use?” And I told him how much?

And he told me… He says, “Oh my gosh.” He says, “That’s not enough.” So we turned around and looking here was Colonel sitting up in the back of the station wagon (chuckles) looking around, trying to see what was going on. So we made the decision that he was probably still groggy enough that he wasn’t gonna come after us. So we opened up the cage door, we opened up the back of the station wagon each grabbed an arm and kind of threw him up into the cage. And he got up and walked around, kind of nonchalant at least, still pretty tranquil from the effects of the ketamine. But at least he didn’t go after us. And of course we made sure the thing was locked up after that. One day Colonel was in the back and…

He’s a big, powerful animal. And he could open those night house doors, if he wanted to. He’d break them open. One day, we had a painter in there painting, and he flung open the door and came walking by the painter. And of course he scared the daylights outta the painter, but he walked past him into the next cage, and we locked him up. Also one day we had jaguars over there, and we had a Jaguar that he got into the cage with that. But they didn’t interact. They were fine.

We got them separated. But those were the days where the old cage type exhibits and the totally unsatisfactory way of keeping animals. The only thing I’d say about those days, is they got people interested in animals. And if you’re gonna get people interested in conserving animals, you gotta get them interested in product first. And that would be the animal itself. And so they were successful in that way. But captive breeding was not a big program back in those days. And it was mainly just educational experience, I guess.

Did you ever consider, or did you ever use regular medical doctors or hospitals to help you?

We did if we had a primate, and then we were also called upon ones too, with a kidney transplant. One of the first kidney transplants that was done, they used two baboons to transplant the kidneys into young a boy. And I was responsible for anesthetizing the baboons, and then they took the kidneys out. But we did call physicians in. In fact the medical examiner down was a good friend of mine. If we had an animal die, that we were really puzzled by what caused the death, I’d take it down to him. And it was a good break in his day, and he loved necropsing into the animals. But if we had a primate that had a problem, we quite often would call a medical doctor, and they were very good about coming and helping us.

And as our collection grew and we got more big apes, gorillas for instance. At the new zoo, we would anesthetize them once a year to give them a physical exam. And we always had a team of doctors there do the exam. EKG and examine them from head to foot. And it was a good break in their day, and it was a good help for us. So we worked together well. Just to remind you to incorporate his question with your answer. Yeah.

What was- What would you say was the favorite part of your job being director?

The favorite part of my job as director, I guess over the years was the planning and developing a new zoo. One that had natural habitat. It was a long process, a very frustrating process. And eventually I think that the product, the new zoo was a very nice thing, but it sure wasn’t an easy thing to do. And I guess that would be the best thing. It was always fun to give lectures to kids and see their reaction. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the experience of taking a kid to zoo for the first time, and seeing his reaction. It’s interesting, boy, they just…

They can’t believe it, you know. Their eyes pop up, and say, oh, well, this is wonderful. And that’s a very rewarding experience. What type of… When you first became a director, were there certain things that you thought, I’m gonna try and implement here, projects for exhibits. This is before you moved.

Were there things that were non zoo director?

I wanna do these. Well we wanted to build natural habitat exhibits for one thing. And we did do one mode exhibit, an elephant exhibit. And the mode was actually the natural ground water because we were only a few feet above sea level there in Crandon Park Zoo. And it worked out well. We built an elephant night house, that consisted of very, very heavy steel bars spaced so that a person could run between them if you had to get away from an elephant. And they worked out very, very well. It was a very nice exhibit.

We built a couple other, I guess you’d call them pit type exhibits for things like aardvark, for instance. Peccaries, small animals like that. And they worked out well, but I wanted to develop a professional staff. And so we tried that as best we could with the funds we had and the personnel we had. We did have some good people there, and they fell into those roles. But as far as having say, a teacher as our education director, we just couldn’t afford it. And we didn’t, but we had somebody that did a good job anyway. Was willing to learn as much as he could about animals and take them out and handle them and show them to the kids.

What’d you love about being zoo director?

Well, one of the things I enjoyed most, I guess, about being a zoo director was getting to know other people in the zoo field. Marlin Perkins, the Bill Conways, whatever. Those people had just been kind of legends up until the time got a chance to meet them and visit with them. And it was fun getting to know them, and seeing their ideas and their outlooks on things. Because you mentioned him, what type of person was Marlin. What kind of outlook did he and Bill Conway.

What was their outlook on the zoo field, or did it stress certain things?

Well, Marlin was kind of a hero of mine ’cause of a zoo parade thing. And I had visions of being something like that one day until I had that disaster television show in Cincinnati. And that kind of tame me down a bit. But he was laid back very sweet guy to work with. I’d say Bill Conway was aloof friendly enough, but maybe not the easiest person to get to know. Did they impart philosophies to you that you kind of gleaned from them or- Well- Yeah, of course Bill Conway was full of philosophies and particular ones I can’t remember except the natural habitat themes, and the things like their exhibit at night animals. And things like that they were always intriguing. And I guess all their they’re talking together kind of melded into one big philosophy.

Were there certain zoo directors that you sought advice from?

Yes, Len Goss was one. Being veterinarian and then the director of then Cleveland zoo. Len was a nice guy, I liked him. And yes, he was one that I contacted. Warren Thomas was a character. Occasionally I’d talk to him, but (chuckles) he was a character. As far as other people, I can’t recall. I talked to different people at different times.

Yeah.

That Warren was a classmate of yours?

Warren Thomas was a classmate of mine. He actually got part of a veterinary degree, I guess, in Peru. And then got accepted to Ohio state. And he was in my class, yeah. He was an interesting guy. When I first talked to Warren Thomas, I’d ask him a question about an exotic animal and he’d always have an answer. Well, after about a year of this, I began to realize that some of his answers weren’t right (laughs). And I started researching and studying these things and then called him on some of this stuff.

But he was a interesting guy to work with. He went to Brownsville, Texas, as a director there. I remember he had one horrible experience there. He used LSD on an elephant. The elephant went crazy, killed himself. But he was Warren Thomas. That was the thing he would do. Crazy things like that.

You mentioned the elephant house that you put together.

Did you do anything with small mammals, or the Africa wild scene?

What were you trying to do there?

With the African… Well, the small animals, the African exhibit area we had porcupines, big crested porcupines. Aardvark. Aardvark were interesting. We came in one day in 1967, September 67. And we found this baby aardvark in the exhibit. And so we didn’t know what to do. And we tried looking at literature, and there’d never been one born and hand raised in captivity before.

So I’ll have to give our veterinarian at the time, Ron Samson all the credit. ‘Cause he developed a formula using (indistinct) which was a formula use for big cats primarily. And he adjusted it as he thought need be and hand raised this aardvark. And we went way out on a limb and announced that the aardvark had been born and all the news media came out, and oh my (chuckle) have we made a mistake here, because that thing could die in a few days. And we didn’t know whether we’d done the right thing, but fortunately everything went well. We had a county wide contest to name the aardvark and things like that. And gave us a lot of publicity. We got other aardvark then after that, we had I think total of 17 aardvark born, yeah.

Did that first public relations surprise you the amount. No, we knew a strange looking animal. If it it’d been a mouse or something we would’ve never gotten it. But it was such a strange looking animal, and an animal that’s one species representing an entire order. So I guess we weren’t surprised by the whole thing. But it worked out well. Thank goodness.

How was the zoo funded?

Was it just a public zoo that was funded by the parks department?

Or how did that work?

Okay, the zoo was funded by the county. It was a county zoo. We occasionally got a little help from the zoological society, if we needed money for an animal. For instance, we got an Indian rhino, and they paid to have it transported. And paid whatever costs were necessary. And more of our zoological society board members was actually the one that got the Indian rhino forest. He was also the one that got the white tiger forest too. Ours was the second white tiger in zoo in this country.

And so we did get a little help from our zoological society, but not a whole lot. But I always felt that the future of the zoo depended upon the zoological society. How well they could develop it, and whether they could eventually take over management of the zoo.

Was the zoo society there, when you started this veterinarian?

The zoo society was there when I started and it had monthly meetings. And I think they had been in existence for four or five years before I got there. We tried to change the character of the board so that we would have a few prominent politicians on there. A few prominent scientists, a couple millionaires. And so we could begin to get things done and that it took a while to get the character of the zoology society board changed so that we could eventually get into developing a new zoo.

What was your part in trying to change the character?

Did you have a role to play or was it beyond you?

No, I was on the zoological society board and the people were good friends. And when their terms expired or whatever, I would urge them to put certain people on the board. And I think that they were professional enough to realize what we had to get done, as far as the makeup of the board goes. We’d been talking about a new zoo since Hurricane Betsy came through there in 1965, and put three feet of water over the zoo killed 250 animals. We knew we had to move the zoo inland. And so we talked about it for five years, and in the meantime, we tried to get our board straightened out, so they could put more pressure on our politicians. And 1970, they passed what they call a decade of progress bond issue in Metro-Dean County. And they put a part of it in the parks department.

$10 million for a new zoo. Well, this was later reduced $8 million (chuckles). But we did get $8 million for a new zoo. I convinced the zoological society board to hire T.A. Strawser as our zoo designer. I had known Terry Strawser since I worked at the Columbus Zoo. He was originally from Columbus. A commercial artist, very good artist. He was a keeper there.

And then he eventually became curator of birds. And so he had zoo experience. Had, I dunno, six, seven years zoo experience. But being a good artist, he decided he would get out of the zoo field. He moved to San Diego and started doing art shows all around the country. Well, he would come to Miami and maybe once every two years. And we would talk about new zoo, and how we would design it if we could. So when the time came to hire a zoo designer, to me he was a natural.

And the zoological society hired him for nine months. His goal was to develop a master plan. I worked with him. And to build a model,. Was seven feet square, as I recall, of the zoo. And he finished this in nine months, and we presented this before the county commission, And of course he did renderings of the exhibits, and it passed the commission’s approval. And then he was hired back again, the following January as our permanent zoo designer. And we got an opportunity to work together again, developing the zoo.

And the county hired a firm. They wanted to hire an architectural firm, to design a new zoo. We said, no. We’re the designers. What we need is an engineering firm to make it work. And they did listen to us, and we did hire an engineering firm, not the one that Strawser and I had wanted. But then I think there was probably political reasons, or maybe financial reasons why this other firm was hired. I don’t know.

And their engineer that worked with us, was a really nice guy, really sharp guy. And he and I, and Strawser took a trip around the United States to visit nine different zoos. One in Canada actually, Toronto Zoo. And we took our plans with us, and we sat down with the zoo directors or the designers and said, this is what we got planned.

What do you think?

You think these will work?

What are our problems?

And I’d have to say that everybody was very helpful. San Diego, Los Angeles, I’m trying to remember Milwaukee, I think St. Louis, Brookfield Zoo, Chicago, Bronx Zoo, Toronto Zoo. Toronto was an absolute disaster. That was a new zoo, had just opened. I don’t know who designed that zoo, but they really didn’t know what they were doing. They had a lion exhibit that the lions jumped out of. They had an elephant exhibit, that I’m surprised nobody was killed, and the elephants were housed in solid concrete wall pens. So that if you got in that pen in front of an elephant, there was no way of escaping.

And he could crush against the wall, or against the floor or whatever. And it was just a disaster waiting to happen. We were horrified when we saw it, we told him. They must have changed him since the (indistinct). ‘Cause I haven’t heard of anybody gotten killed up there but it was amazing. And we came back with some really wonderful ideas. We also took one of our African Safari’s. We took the zoo designer with us, to look at habitat since we were gonna develop the African habitat as one of the first areas, Asia and Africa together.

And I think that all gave us a new perspective on things too. We’re gonna talk a little bit more about those particular subjects. But let me go back to the zoo society for a minute. You mentioned a white tiger, and you mentioned rhinoceros, Indian rhinoceros.

Was that animals that you as you’re director were soliciting an interest in or did they just arrive in your doorstep?

Oh no. We solicited an interest in them. Actually this millionaire, Ralph Scott was very active in the zoo society and with the zoo. Had mentioned that he might be able to get these animals. And we said, sure by all means. And of course then the white tiger was the first thing he got and that brought us all kinds of publicity. The tiger unfortunately died suddenly two years after we had gotten it. It fed in the afternoon, the next morning we came in, it was dead.

So that was when I did take on the medical examiner and we looked through it and sent tissues off the CDC and they finally decided it died from a distemper virus. But it just very suddenly overcame it and killed it. It had been vaccinated, so it was a puzzle. But when he mentioned Indian rhinos, of course we had black rhinos, and we were very interested in Indian rhinos. We knew there endangered status and we felt it was important to get new blood into this country somehow, and eventually made him up with a female. And we did get this male very nice animal.

Did you make daily rounds as zoo director?

I made daily rounds to all exhibits and talked to as many of the keepers as I could find. And I tried to keep track of everything that was going on. I think it’s important that if you’re gonna manage something, you gotta get out there and see what’s going on. Yeah.

How would you describe your management style?

Well, I think there are two basic ways of managing an institution or managing a group of people. One is to be a good old boy, be a friend with all of them and slap them on the back and go out drinking with them, and whatever. The other one is to not socialize with them and maybe only at a yearly party or something. But be a bit apart from… And that was really my way of doing it. Not that I tried to be aloof or anything, but just they weren’t a part of my life. I’ll put it that way. Whereas I had an instructor in veterinary college once who was one of these guys that was everybody’s buddy and it just didn’t work out too well.

And so I saw that wasn’t working and I think maybe it’s a little better if you’re a little bit separated from the employees you work with.

How involved was your family in your profession?

Well, my family was involved in one way in that the animals I brought home to bottle raise for instance, like a lion, and a tiger, and cheetah, puma. We had a marmoset. One of the problems I faced, veterinary problems I faced was a gelada baboon that we had gotten a pair of them. They’d been there I think five years, had never bred, but the female started getting a big belly on her and we thought maybe she was pregnant. But she started laying around on the cage on her back and pushing her feet against the wall. And obviously in some discomfort, she did this for a couple days, and I thought she’s gotta be in labor and having problems delivering. So we anesthetize her and delivered her baby. It a was healthy baby.

And then sewed her back up, put her back in the exhibit again with the male. But we took the baby home and hand raise it. And our kids especially were involved with hand raising it. They named it David Crockett (chuckles). I guess, partly because of the funny way the hair stood up on the top of the head. But they were involved in taking care of some of the animals and they were very good at it. And of course all the neighborhood kids could come over and see them. So they were involved in that way.

And then almost every evening we rode our bikes and we were so close to zoo. We just ride off to the zoo, ride around the zoo at night. That gave me another way to look at the animals out there. And of course there were little lakes and ponds all through the zoo. And so I used to fish out there too. Get some big fish in those lakes (laughs). Now you mentioned the Hurricane Betsy in 1965. Yeah.

What happened?

1965, that was an interesting experience because I had a gallbladder attack in the summer of 1965 in fact two of them. And I went to see my physician and he said that… They did some tests and he said, “You’ve got gall bladder disease “and you’re gonna have to have it taken out.” So I had the surgery, but unfortunately I had it done the old fashioned way with a big incision across my belly. You know, they’d reach in and pluck it out, and tie it off and cut it out. But unfortunately, Hurricane Betsy was coming at us from the Atlantic. Now she was coming north of the Bahamas and usually those hurricanes curb around to the north and the Gulf stream, which flows past Miami, usually carries them back up north. So we weren’t really too concerned about it. But towards the end of the week, we could see it was coming at Miami.

So my wife got the kids together and the dog, and she went into town and got a motel room. And then the thing curved north. So she packed up the kids, went back home again, and that afternoon, the thing turned around and came back south. So it came right square through Miami. And she was unfortunate, got another motel room. But we were in the top floor, the surgical ward of Cedars Hospital, and boy, the building shook so badly that the nurses got frightened, went downstairs and left all the surgical patients up there alone. We were pushed out into the hallway. So we’d be away from the windows in case the glass started flying.

But then the next day they came and got us. Now that storm also broke loose, a barge that broke one of the bridges out at Key Biscayne so we couldn’t get home. Couldn’t get to the zoo. The army corps engineers came in and built a temporary bridge, a Bailey bridge across that span that was missing. And they let us out there. Of course, we lived out there, and then we found that we could find the watermarks in the buildings where it’d come up three feet over the walkways. And they made a mistake when they evacuated the zoo, bagging all the reptiles, but leaving them on the floor of the reptile building. And they were all drowned, and we lost a few big animals.

But mainly they were small and mainly reptiles. And then we had to regroup and get everything cleaned up. And that was really what started us seriously thinking about building a new zoo away from the ocean.

Did you have a hurricane plan before this occurred or emergency plan for fire and different things and were hurricanes part of it?

Yes. We had an emergency plan for… We really wouldn’t have any fires out there. Everything was kind of isolated. But for hurricanes, yes. We had a plan. We went through who did what when, and where we went, and we listened to the different hurricane alerts. So we could tell how much time we had left to get things organized.

And afterward, were there adjustments to the plan, as you looked at the devastation and what had occurred?

The only adjustments we made to that plan after the Hurricane Betsy was we didn’t put the reptiles on the floor anymore. We put them up in the exhibits. We bagged them all. We only had a few poisonous snakes ’cause I really didn’t like keeping poisonous snakes. We just didn’t have the antivenom in there to treat people. But we had the Miami Serpentarium and Bill Haast right down the street from us. I didn’t feel comfortable keeping poisoning the snakes. I think you really have to have specialized people and specialized exhibits to keep things like that.

That are that dangerous. And did other zoos… You lost a number of animals. We lost a lot of animals during that hurricane and the other zoos, some of them offered to keep some of the animals. And it seems like we did ship some of them out to other zoos. Everybody was concerned. We got a lot of calls from different people and wanting to know how things were going. What was the…

So in the aftermath, you lost animals. Were your thoughts, let’s build a new zoo. Were your thoughts we need to replace the zoo, was the city government coming to your assistance to say, okay, we have to rebuild and we’ll do it right here.

How do those things start to evolve?

After the Hurricane Betsy problem, we knew we had to refurbish the zoo as best we could without getting into a lot of big expense. And we knew we had to build a new zoo. One thing the county did was they instituted an admission charge to the zoo, to build up a reserve for funds. Up until that time it had been a free zoo. We averaged over a million people a year in that zoo. (indistinct) it instigated mission why it went down a bit, I think 800,000 or something. But there was still enough money coming in, that they could provide us with more money for doing what we had to fix the zoo up. But our goal, our focus was to develop a new zoo.

Were the animal dealers helpful?

Were you looking to replenish your specimens. The animal dealers after the hurricane, I wouldn’t say that they donated animals to us or anything like that. They helped us in securing what animals we needed, but mainly again, they were reptiles, ’cause the male did pretty well. There was a couple mammals that we lost. I can’t remember what species they were right off hand.

Did you notice any behavioral differences with the animals after the hurricane?

We didn’t notice any behavioral differences with the animals after the hurricane. No. Things went pretty well back to normal again.

How long did it take to reopen the zoo after this devastation?

It probably took us two weeks to reopen the zoo again. And then of course all exhibits weren’t there, but there’s construction out there, was basically chain link fences, concrete buildings with outside exhibits so that water didn’t hurt them at all. Few trees fell down, maybe tore down a fence here or there, but that was easily rebuilt and replaced. So we were able to get things back together, fairly rapidly after the storm.

Was there any major hurdles in doing this?

I wouldn’t say there were any major hurdles in getting the zoo opened. The major hurdle of course, was trying to get a new zoo built. And that was an interesting proposition. That is a lot complicated experience. Playing the political game again, we knew that we should get the designer from the (indistinct) department involved in our design, whether we paid any attention to him or not, at least say, that he had input (laughs). And he was a strange guy. Fred Boragair was his name. So we made arrangements with Disney, to tour Disney World before it was open, while they were still developing it.

And we took Fred with us up there, and were able to go through the haunted house, a lot of the attractions. And they showed us behind the scenes, how everything worked. I mean, it was quite a fantastic trip. We knew a guy that was one of the designers up there. And so he got us into these different areas and we presented the master plan we had finally to the parks department, to the whole personnel. Well, Fred, all of a sudden from being a friend and helpful became our enemy. And he was really critical. And finally, after we had explained how all this stuff was gonna work in spite his objections, he said in his classic comment was, “It won’t work, it’s too logical.” And I thought, wow, Fred, that’s a nice compliment I appreciate it (laughs).

Then of course, we got things well along. Well we had some problems with the architectural firm, engineering firm. Because they ran into over costs on overruns. And instead of… I think they had a $450,000 contract. It ran it up to around 600,000. Well, about that time, we got a new parks department director. Fellow used to work in a parks department today, had known years before.

And he came in and he hired a fellow who kind of a strange duck, in that he didn’t get along with anybody. But he put him in charge of the project. So he essentially took the design thing out of our hands out of Strawser’s hands and my hands, and put it in his hands. And our objective was just to come up with suggestions on how the thing was to be designed. Well, he didn’t know anything about zoos, so he almost had to take our suggestions. But then we got into this thing, and he was in charge of it for a of couple years. And we ran into these tremendous over runs, and over costs and the architectural thing. And newspapers got a hold of it, and they made a big scandal out of it.

Oh, this is gonna cost so much more, where’s all this money going and all that. Well at that time Strawser and I breathe the sigh of relief ’cause it wasn’t our responsibility anymore (chuckles). It was his, and he’d been handling for the past couple years. Well, at that time I was president of the NZPA, and my term was up in September. I think it was 77. And the dust began to settle and went in and went in and talked to our new parks department director. And I said, you know… And by that time they had fired the project manager who turned out was a fraud.

Nobody had bothered to look into his credentials and it rearranged the staff a little bit. But I went in and talked to our parks department director and I said, look, this guy is really responsible for the whole screw up.

Why is he still working here?

And couldn’t get an answer. Well, couple months later I was removed as zoo director. And that guy was put in as a zoo director, Bob Yokel. Who knew nothing about zoos, had no experience with zoos, and had reputation for being a horrible person to get along with. Well, I found out a little later that his relationship with the parks department director went back years before he used to be his bartender (chuckles). So it was literally a conversation. And then you were just given…

You’re no longer zoo director?

Right. I was assigned to be the education director. And I worked with Bob. You know, he’d get a call on the phone about an animal, and I could tell he was talking about an animal and my desk was right next to his. So I’d write out something for him to say about the animal. Found in Africa, lives on the (indistinct). And then he’d recite over the phone. He knew nothing about animals.

Absolutely nothing. And after he became zoo director, he used to go to the zoo conferences, and instead of going to the scientific meetings, he’d go off and play golf, or go out and party. And was several years after that, my colleagues in the zoo profession thought I was still the zoo director down there. I kept saying no, no, it’s Bob Yokel. “Who’s he?” You’ve been coming here for two years, you guys don’t know him yet (laughs). Well, let me jump back while you were zoo director, you and maybe this works beyond. You had stated that you have to have a sense of humor when working at a zoo. Were there any funny situations that you could share with us that demonstrate that.

Funny situations?

Well, let me think on that a second. We had some interesting things come up, fortunately that we could resolve.

Where your sense of humor came in handy?

Yeah and a little bit of courage too I guess. One night of that, we had a night watchman who was in his early seventies and essentially deaf. I mean, you’d have to yell at him to make him hear you. And I used to go out at night at the zoo. I walk out there and come in the back gate and close it. And I’d stand behind a tree, just to check and see if he was checking and he’d come along and walk right by me. Never knew I was there. But he had a bad habit of checking every lock and he’d shake every lock.

And he did this for a couple years, and they started to break. He’d just wore them out (chuckles). But one night he called me, it was 11 o’clock at night and I’d just gone to bed. And he says, “Doc.” He says, “The hyenas got out and they chased me “back to the office, come out, do something.” So I got in the car and drove out there and I kept thinking, I was only five minutes away.

I kept thinking all the time, what am I gonna do?

How am I gonna catch three hyenas in the middle of the night?

So I figured the only thing I could do would be to try and shoot them with a capture gun, and tranquilize them. So I drove up to the hospital, I (indistinct) up six darts, figuring I could miss each animal one time. But I had three of them. I had to make a connection. It’s fortunate they were hyenas. If it had been wolves, or coyotes, or something else they’d have been gone. But hyenas are funny animal. Very curious animal.

I got in the pickup truck and I drove around the zoo and there was no lights in the zoo. It was perfectly dark. Couldn’t find the hyenas. So I figured, okay, I’m gonna have to walk around. So I got outta the truck, and I started walking around the zoo went back through the children zoo, back to the very back of the zoo. And there behold, there were the three hyenas sitting in the walkway looking at me, boobing there heads the way they do and letting out who hoot here and there. So finally one of them came running up, maybe 10 feet from me bobbing around like this. And he turned around, I shot him right in the butt (chuckles).

He ran back there with that dart and the other two were sniffing around what’s going on, what’s going on. So I went up while they were there, walked right up to them and shot the other two. Had all three of them knocked out within well, 45 minutes after they’d escaped. Thank goodness. Then we had to figure out what to do with them. And they weighed 95 pounds a piece. So I had to go back and get the night watcher and to help me lift these things into the truck. And we went over to the lion exhibit and emptied out.

We put all the lions in the night house, and drug these things into the outside exhibit. But they had gotten out of a giraffe exhibit that had rock base to it. I mean, they were big boulders in there, and how they dug out, I don’t know. But they digged and hyenas can sure dig. But you almost have to have a sense of humor when you do things like that. We had another situation out there, We got in… We had two cape buffalo in the old zoo. We got in a trio of forest buffalo.

Oh, forest buffalo weighs what?

600 pounds, 700 maybe for the male. Cape buffalo weighs 1200 pounds. So they’re half the size. But we did not cut down on the amount of food. So they got really fat and we just didn’t keep on top of the whole thing. Well, one day the keeper came over and he said, “You know, there is one female is walking around “with her tail stuck straight out, “and she’s kind of waddling around.” And I went overlooked it and I said, oh my god, it looks like she’s in labor (chuckles). She so damn fat, we can’t tell whether she’s pregnant or not. So I told him the night keeper, I said to keep an eye on her.

I came home in middle of supper, six o’clock or so he called and he said, “She’s down, she won’t get up.” Said, oh god, we gotta do a cesarean section now. So everybody had gone home. We had the night keeper and we had a friend of ours, a Mexican fellow who had just gotten his veterinary license. It was a neighbor of ours. So I got him, I got the guy that worked up at the gas station a night keeper called in one of his buddies. So there were five of us there, and we went over to the exhibit and there was no light in the exhibit. So we rigged up a cube beam light on the fence, hooked it up to the battery in the car. And I went, gave her a dose of rompine anesthetizer.

And I had all the instruments there, and we tied her front legs to one palm tree back legs to another palm tree and shaved her side, left side and got ready. In fact, I started the incision and it started to pour down rain. So we covered up the instruments and the incision with the sterile gowns we had there, until the rain passed. Well, then I cut into the fatty layer, which was extensive on this animal. And of course it bleeds a lot when you cut it in the fat and the guy that was holding the flashlight passed out, fell over in the sand (chuckles). So the night keeper grabbed him, held him up with the flashlight. And we went in, we cut open the animal and got into the uterus, got the calf. It was 65 pound calf.

Probably about 15 or 20 pounds overweight, dead and pulled it up. And then we had to suture her up. And of course it only takes about 15 or 20 minutes to make all the incisions. It takes a couple hours to sew her up. And I sewed up the uterus and then the muscles the abdominal muscles, and we got just about sewed up and started pouring down rain again. And we covered everything up. And then the shower passed and we finished sewing her up. Well, she did fine.

We gave her a long acting penicillin, and I figured, okay, I was gonna have to give her a shot every other day, a long acting penicillin, just to make sure we didn’t get peritonitis. This whole thing. Well, the first shot wasn’t so bad. You know, she stood there and bang. I bumped her right in the butt, the second day, two days after that second shot. When she saw me coming, she ran and hid behind trees, and there was rocks in the exhibit. So we had to sneak around, try and get a view of her so we could shoot her. But by the third injection, she was almost impossible to shoot.

We did get it into her. She survived and she had several calves normally after that. So it was a successful procedure. Now from the crazy things that happened in 1975, there was a report that was submitted that some of the animals were being abused.

Was there any evidence of abuse and how did you handle that kind of situation?

Was it Crandon Park Zoo?

1975. It must have been Crandon Park Zoo then. We had keepers that… In fact, I remember the television reporter that came out to investigate animal abuse allegations. He said, “You know, here are a list “of 10 complaints or something.” And one of them was a male lion that had gotten sick and I treated, and then it died. And the time we didn’t even have a male lion, and no lions had died out there. I had treated one lioness that had been sick. And this sort of thing we had some (indistinct) that was one reason why I was hired to begin with.

Was because we had these people that… You know, the (indistinct) that thought they were doing something good by complaining about the way animals were kept in cages, I guess. But we pretty well dispelled that and nothing really came of that. Can you tell us… We’re talking about stories.

Can you tell us about the deer story?

Yeah, you know, one thing about working with zoo animals and wild animals in general, is that they’re unpredictable. I think people buy exotic animals as pets thinking that they’re gonna tame them down. They’re always gonna be nice animals, but they’re wild animals and they just don’t make good pets. They have some luck with things like parrots and minor birds, I suppose. But as far as ocelots and lions and things like that, no. I had an incident happen to me when I first started to work at the Crandon Park Zoo. I was sitting in the office one noon time, eating my packed brown bag lunch, and a lady came into the office and she says, “Oh, the deer is attacking the newborn fawn over there “and it’s gonna kill it.” Well, I knew what she was talking about. She’s talking about the Costa Rican deer, which is the small subspecies that are common white tail and the male weighed, maybe 110 pounds or something like that.